Chicago may be the most dangerous city in North America for birds, but a group of volunteers is trying to change that. Lake Superior was once thought to be too cold for algae blooms, but not anymore. Scientists are researching the causes and finding ways to stop the blooms. And, after months of lockdown, Great Lakes aquariums reopen to visitors. Find out if the fish have missed the people.

WHERE WE TAKE YOU IN AUGUST

GREAT LAKES LEARNING:

Explore this month’s hands-on lesson plans designed to help your middle schoolers understand the Great Lakes — all at home or in the classroom. They’re aligned to standards and free to download.

Lesson Plans

Have a question about the Great Lakes or life in the region?

Ask Great Lakes Now, and if we can answer it, we might loop it into our coverage so others can learn too.

Submit Your Question

When to Watch?

Check your local station for when Great Lakes Now is on in your area.

Great Lakes Now

Premieres on DPTV

Tuesday, August 30, at 7:30 PM

STATIONS CARRYING THE SERIES

DPTV

Detroit, Michigan

WEAO

Akron, Ohio

WNEO-TV

Alliance, Ohio

WCML-TV

Alpena, Michigan

WDCP-TV

Bad Axe, Michigan

BCTV

Bay County, Michigan

WBGU-TV

Bowling Green, Ohio

WNED-TV

Buffalo, New York

WCMV-TV

Cadillac, Michigan

WTTW-TV

Chicago, Illinois

WVIZ-TV

Cleveland, Ohio

WKAR-TV

East Lansing, Michigan

WQLN-TV

Erie, Pennsylvania

WCMZ-TV

Flint, Michigan

WGVU-TV

Grand Rapids, Michigan

WPNE-TV

Green Bay, Wisconsin

WGVK-TV

Kalamazoo, Michigan

WHLA-TV

La Crosse, Wisconsin

WHA-TV

Madison, Wisconsin

WNMU-TV

Marquette, Michigan

WHWC-TV

Menomonie-Eau Claire, Wisconsin

WMVS-TV

Milwaukee, Wisconsin

WCMU-TV

Mt. Pleasant, Michigan

WLEF-TV

Park Falls, Wisconsin

WNIT-TV

South Bend, Indiana

WCNY-TV

Syracuse, New York

WGTE-TV

Toledo, Ohio

WDCQ-TV

University Center, Michigan

WNPI-TV

Watertown, New York for Ontario signal

WPBS-TV

Watertown, New York for U.S. signal

WHRM-TV

Wausau, Wisconsin

Making Cities Safe for Birds

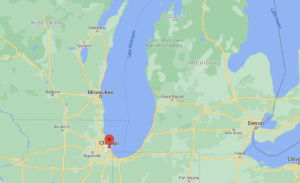

SEGMENT 1 | Chicago, Illinois

Each year, millions of birds migrate through the Great Lakes region. A sizable number of them never make it to their destinations. Many die or are seriously injured after crashing into windows of buildings.

Chicago, according to researchers, is the deadliest city in North America for migrating birds. But some volunteers, advocates and even politicians have made some strides in making the Great Lakes region safer for birds.

On any given morning during migration season, Annette Prince and her team of volunteers patrol the streets of downtown Chicago. She is the director of the Chicago Bird Collision Monitors.

With a net in one hand and big bag in the other, Prince visually sweeps the edges of buildings, looking for birds, dead or injured, that have collided with one of Chicago’s numerous skyscrapers.

“Essentially having flown all night, they’re looking for a place to rest all day,” says Prince. “Like you’ve driven your car all night. You’re looking for a place to rest and find something to eat. They’re using the city, but the city is filled with a lot of dangers that get them in trouble.”

Established in 2003, the mission of Prince’s volunteer organization is to protect migratory birds through rescue, education and outreach.

“We cover about one square mile of downtown and in that square mile every year we pick up about 5,000 birds,” she says. “If you multiply that by all the areas along the lakefront, you get into the tens of thousands of birds hitting windows either dying or injured.”

Since 1995, Chicago Bird Collision Monitors and other groups have worked with commercial building managers under the Lights Out program. Birds are attracted to the lights of buildings, so during migration season, tall buildings turn off or dim their decorative lights at night to reduce collisions.

In response to the high number of migrating birds that are killed each year in Chicago, new city regulations are in place that require all new buildings and renovations to be more bird friendly.

The State of Illinois recently passed similar legislation which applies only to government buildings. The new guidelines include measures such as reducing window reflections by incorporating patterns etched into the glass, frosted glass or applying a special film to make the glass more visible for birds.

Pam Karlson, who lives on Chicago’s northwest side, has devised a simple and very cost effective solution for preventing bird collisions at her home. She uses Post-It Notes, dozens of them, on her living room picture window.

“So it’s a temporary solution. It’s cheap. There’s a ton of them up there,” says Karlson. “Obviously, some people might think it looks kind of hokey, but it works.”

A professional garden designer, Karlson has created a small paradise in her backyard, including a waterfall and stream, that attracts hundreds of birds each migration season. “So now we get great blue herons,” says Karlson. “We had a green heron, Merlins like to fly over it. Certain warblers are attracted to water, Yellow Warblers seem to really enjoy it too.”

Karlson says her goal has always been to give migratory birds a safe haven, where they can feed, rest and refuel to continue their journey.

Here is other Great Lakes Now work on birds around the Great Lakes:

Superior Blooms

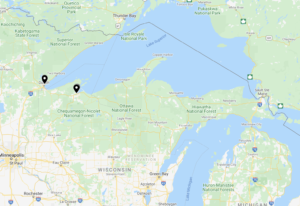

SEGMENT 2 | Duluth, Minnesota; Ashland, Wisconsin

A few anecdotal reports of blue-green algae on Lake Superior have come in over the years, but the first confirmed sighting was in 2012, following a massive rainstorm that dumped up to 10 inches of rain on Duluth and caused destructive flooding.

Another storm in 2018 caused serious flooding, this time in northwestern Wisconsin, also along the Lake Superior shoreline.

Soon after that event, a blue-green algae bloom appeared in the water for parts of 50 miles, stretching from the Apostle Islands to Superior, Wis.

“Big portions of it turned really opaque green, like melted crayon-green,” described Bob Sterner, director of the University of Minnesota-Duluth’s Large Lakes Observatory. “And that’s when we knew we had something going on that we really needed to get to the bottom of.”

Scientists believe there’s a strong link between the storms, the algae blooms and climate change. Minnesota is already experiencing more frequent extreme rain events, and they’re expected to become more frequent as temperatures continue to rise.

But scientists are still working to better understand the precise mix of factors that determine when and where blooms on the lake. This summer, a crucial part of that effort involved researchers from universities, state and federal agencies from around the region undertaking a coordinated effort to intensively study and monitor Lake Superior.

On a recent hot, still July day, Northland College researcher Reane Loiselle steered a flat- bottomed boat into Chequamegon Bay on Lake Superior, off the shore of Ashland, Wis.

Her destination was called, simply, CB-1, a spot a quarter mile or so offshore, in 17 feet of water — one of 31 sites along the South Shore of Lake Superior that a team of researchers is sampling on six different days throughout the summer.

Loiselle drops a tool called a water quality sonde into the lake. It gathers data like water temperature and the amount of algae in the water. She also collects water samples to take back to the lab, where researchers will look at everything from the tiny microbes that live in the water, to nutrients in the water — such as phosphorus — that the algae needs to grow.

“So we’re trying to analyze for the kinds of things that would tell us, okay, what are all these different pieces to the puzzle?” says Matt Hudson, a water scientist and associate director of the Mary Griggs Burke Center for Freshwater Innovation at Northland College.

“Our goal is to be able to tell the story of how a bloom evolves in Lake Superior, what drives it?” said Hudson. “And then ultimately, what can we do about it?”

Here is other Great Lakes Now work on algae blooms on Lake Superior:

Aquariums Re-Open

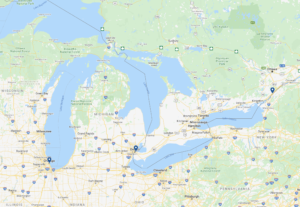

SEGMENT 3 | Detroit, Michigan; Chicago, Illinois; Brockville, Ontario

After months of cautionary shutdowns, aquariums around the Great Lakes region are welcoming visitors back … and wondering if the fish and other creatures noticed the absence of human guests.

Or at least the physical absence since aquarium staff — and some fish, fowl, mammals and insects — still connected with people virtually during the first several months of the pandemic.

With social media and other virtual programs, the Shedd Aquarium in Chicago gave audiences a behind-the-scenes look at the care and training of the animals. In the process, a social media star was born. While humans were experiencing restrictions, Wellington the penguin was enjoying some new found freedom. He was able to explore the aquarium and visit exhibits that would have normally been off limits because of crowds.

Wellington and a few of his penguin friends even had an opportunity to visit museums around greater Chicago. Shedd shared the penguins’ adventures on social media. “We heard from people all over the world about how much joy these penguin field trips were bringing them,” said Kelsey Ryan, science and communications manager at the Shedd.

The penguins are back in their exhibit now, and Shedd is once again welcoming visitors. But like many aquariums they were concerned about how the lack of visitors may have impacted the animals. They tested the water in the habitats looking for hormones that would give researchers clues: were the animals excited or stressed when guests were in the building or when they weren’t?

Research at the Shedd so far indicates visitors didn’t have much impact. “They don’t seem to care that we’re here or not, at least with this study’s outcome or at least at the moment,” said Austin Happel, a research biologist at Shedd Aquarium.

Across the Great Lakes, at the Aquatarium in Brockville, Ontario, the pandemic forced staff members to change their training methods to protect animals like the otters that were susceptible to getting COVID. Trainers had to stop using whistles and would emulate the sound of a whistle from underneath a mask.

The Aquatarium also started virtual tours that included a live component with a host that gave viewers a behind-the-scenes look at otter training.

“They got to go live with our otters and see how they were trained and just learn a little bit more about them, what we do with them and how much we love them.” said Jennipher Carter, director of exhibits at the Aquatarium. The tours were so successful that they started a virtual experience designed specifically for elementary school students.

Virtual classroom tours also became an important part of keeping the community engaged at the Belle Isle Aquarium in Detroit. “We started doing live virtual events for classrooms where the classroom would tune in to the aquarium and our staff would walk around and do their presentations online and take questions from the children,” said Dr. Paul Shuert, curator of the Belle Isle Aquarium.

The pandemic shutdown gave the Belle Isle Aquarium a chance to make improvements. The aquarium spent $1.2 million to renovate and add exhibits. They added a garden eel exhibit and eight new saltwater tanks. Visitors are back, and staff have restarted in-person programs for public school educators.

All the aquariums are once again open to visitors and according to Belle Isle Aquarium Senior Aquarist Amanda Murray there is nothing like having people back in the building. “It’s really exciting because we put a lot of work into the aquarium and with no one to see it it was kind of sad. I’m so excited to have people enjoy these fish like I do.”

Find all of Great Lakes Now’s work about aquariums here:

Videos from Episode 1028

Subscribe on YouTube

Featured Articles

Digital Credits

The Great Lakes Now Series is produced by Rob Green and Sandra Svoboda.