Bureaucracy, politics and “regional pork barrel” hinder progress

Removing contaminated sediment from the Great Lakes started at a small inlet in the Trenton Channel of the Detroit River called the Black Lagoon.

“Black Lagoon” Trenton channel, Detroit River, Photo by epa.gov

Its name refers to the stew of toxic PCBs, oil and grease in its sediment.

It was 2005 and the Black Lagoon was the first Great Lakes restoration project under the recently passed Legacy Act in the President George W. Bush administration.

The site was selected because it was in the heart of the Rust Belt’s industrial past and the “contaminants are well known and they are confined to one area making it possible to improve the environment quickly,” according to a U.S. Environmental Agency press release at the time.

The Legacy Act focused on the decades-long overdue work of removing toxic sediment from multiple sites in the Great Lakes region. Their origins went back to the era when waterways were the repository for industrial waste.

It was the precursor for what is now widely known as the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative (GLRI), the EPA’s program that works on a variety of projects across the region.

The Black Lagoon was cleaned up for less than $9 million in short order and has been renamed Elias Cove allowing it to shed its previous identity.

But cleaning up the toxic sites in the Detroit River has become an ultra-marathon instead of a 10K run and a fast start like the Black Lagoon action did not translate to a sustained effort.

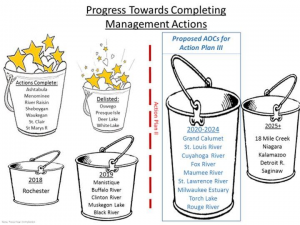

Status of cleanup of contaminated sediment in the Great Lakes region. Image by U.S. EPA Great Lakes Office Chicago

At a recent U.S. EPA conference on the status of the cleanup of the 31 toxic sites in the region, the emphasis was on the 11 sites where work is complete or within a few years of it. That’s 13 years after the Black Lagoon project.

And the Detroit River received only a brief mention in a “bucket” of locations that would “make progress towards completing management actions” in 2025, or later.

Asked why the long, moving timeline for the Detroit River, the EPA’s Tinka Hyde cited the complex nature of the river’s issues like shipping and identifying the sources of the pollution.

But is it that complex?

2025 is “doable”

Great Lakes scientist Raj Bejankiwar told Great Lakes Now that removal of the toxic sediment in the river is “expensive, isn’t difficult” and completion is “doable” by 2025.

Bejankiwar is Deputy Director of the International Joint Commission, the U.S. and Canadian agency that advises the two countries on trans-border water issues. He has a close-up view of the river from his office in Windsor, Ontario across from Detroit.

Raj Bejankiwar, Deputy Director of the International Joint Commission, Photo courtesy of GLN

Bejankiwar said the river has a number of sites but they tend to be smaller and “science is not a barrier” to removal of the toxins. Further, he said once a cleanup process starts, “it moves quickly.”

One impediment cited by Bejankiwar is the structure of the federal funding under the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative. Its year-to-year nature makes it difficult to plan, he said.

Clean-up of contaminated sites in the region has received approximately $100 million each year since 2010 according to the EPA’s Hyde who runs the agency’s Great Lakes office in Chicago.

Citizen demand

If science isn’t a barrier and money is available, how does cleanup of the river accelerate?

“Citizens have to demand that cleaning up the river is a priority,” Nick Schroeck told Great Lakes Now. Schroeck is a professor and environmental attorney at Wayne State University in Detroit.

“Where you’ve seen a faster response from federal and state agencies on cleaning up toxic sites, it almost always is the result of public pressure,” according to Schroeck.

He says because the contamination is spread out over a significant portion of the river, ”it’s harder to galvanize public support.”

Enter Politics

Then there are the politics of a multi-billion dollar endeavor that spans eight states as well as ten federal agencies – and it has to be funded by Congress every year. Toss in a President who would like to eliminate all funding for the lakes, and that’s a lot of stakeholders whose priorities have to be considered.

Another complication is that those members of Congress who support funding of restoration want a piece of the federal pie. In addition to their good intentions, bringing money home for their projects is key to getting re-elected, no matter if the project should be a low priority in the big scheme of restoring waterways.

Boulders on Northerly Island failed to stop erosion that lead to a partial closure of the site, Photo courtesy of Gary Wilson

For example, Illinois secured $6 million in federal restoration money to restore Chicago’s Northerly Island, a spit of land that the City of Chicago had already touted in a promotional video as providing “unparalleled access to the natural prairie and cityscape.”

The video referred to Northerly Island as a “hidden oasis that provided daily doses of nature.”

In spite of already being in a natural state, Chicago – with the help of the Army Corps of Engineers – found some “unused” restoration money and the “salvage”as it was called was used to remake the site.

Today, Northerly Island is only partially accessible to the public because of design and engineering failures resulting from the federal Great Lakes restoration project work.

What could have been accomplished with that $6 million if it had been used for the Detroit River or one of the other contaminated sites in the 2025 or later “bucket?”

It’s this type of management that caused veteran Great Lakes policy adviser Dave Dempsey to say “the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative has done a lot of good, but it’s also our regional pork barrel.”

The official restoration website lists 4,000 projects across the basin with a total expenditure of over $2 billion.

Few options

If the Legacy Act can’t deliver, there is another tool to be used, says Wayne State’s Schroeck. But it too has limitations.

“Citizens can request EPA investigate a site to determine whether it should be added to the Superfund list.” That could allow the agency to clean up the site first and recover costs from the responsible parties later which would expedite the process.

Superfund site in Wisconsin, Photo by Markzvo via wikimedia

But the problem with Superfund is that “there’s still a backlog of sites to be cleaned up from the original list in the 1980’s because the program isn’t funded,” Schroeck says.

With Superfund likely off the table, that leaves cleanup of the Detroit River with Great Lakes restoration and the Legacy Act. That means completion is far from certain according to Richard Hobrola, who manages the Michigan program for the Office of the Great Lakes.

“It’s certainly a possibility” that Great Lakes restoration could lose Congressional support before the river is cleaned up, Hobrola says.

Another potential barrier is that restoration and Legacy Act funding “require a significant local match” that the state and local governments will have difficulty in providing, Hobrola says. That leaves it with those responsible parties and back to a long, uncertain timeline which likely will extend past 2025.

“If potentially responsible parties can provide local match, and if Congress continues to support the GLRI, I don’t know of a reason the cleanup can’t be completed, even though it may take a long time,” Hobrola says.

That’s likely beyond 2025, according to the U.S. EPA. – at least 20 years after the Black Lagoon cleanup.

The U.S. EPA did not respond to specific questions about the Detroit River. An agency spokesperson told Great Lakes Now that along with its partners, they are making “incredible progress” since 2010 on cleaning up toxic legacy sites in the region.

Featured Image: Aerial shot of the Detroit River, Photo by Aaron Headly via wikimedia cc 2.0