The heady days of Chicago holding outsized influence over Great Lakes issues could be waning.

Chicago has been riding a wave of Great Lakes clout. It’s home to executives, agencies and organizations that, along with Ann Arbor in a supporting role, have been the Mecca of Great Lakes policy for well over a decade.

That’s notable considering it only has 30 miles of shoreline and when you travel a bit west, it’s corn country, and there’s no water as far as you can see.

Former President Barack Obama is from Chicago and has been referred to as “the best friend the Great Lakes ever had.”

Cameron Davis is from Chicago’s North Shore. Davis, who first worked as an advocate and then took a job at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, spearheaded Obama’s $2 billion Great Lakes restoration program. The EPA’s Great Lakes office is located in Chicago.

And Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel while a member of congress helped generate momentum for federal funding for the lakes.

His pitch to skeptical congressional colleagues was that the Great Lakes are “our Grand Canyon.” The implication? If you support the Grand Canyon, you should support the Great Lakes. And they did. Before becoming mayor, Emanuel served a stint as Obama’s chief of staff.

Chicago is also home to David Ullrich, a career Great Lakes executive who for the past ten years led a U.S. and Canadian group of mayors who advocated for the lakes.

The group was founded by former Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley – the king of clout — who wanted mayors to have a seat at the table on Great Lakes issues. He hired Ullrich who put the mayors on the D.C. radar and was known to have policy influence beyond his official role with the mayors’ group.

Things change

President Trump has replaced Obama, and he is a policy wild card with no Chicago connections except that one of his towers is there. In his campaign, Trump made the EPA a bete noir and an example of what inhibits economic growth.

Cameron Davis has left the EPA and likely won’t be replaced because budget and staff cuts are on the horizon.

Mayor Emanuel is embattled with an out of control murder rate and federal investigations into police misconduct. The city has financial problems not of his making that have reduced Chicago’s debt status to junk levels. That leaves one to wonder how much time he can devote to the Great Lakes.

David Ullrich announced his retirement from the mayors’ group and that, coupled with Davis’ departure, means a wealth of institutional knowledge has left the policy arena.

The Great Lakes Commission’s Tim Eder has worked with both Davis and Ullrich and said their departures leave “big shoes to fill.”

Too much influence

Not everyone will be saddened if Chicago’s Great Lakes star dims. Many who closely follow the issues have long thought the Windy City has been too influential.

It starts with the Chicago diversion from Lake Michigan.

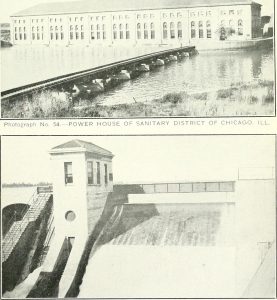

Diversion of water from the Great Lakes and Niagara River, courtesy of The Internet Archive Book Images

This is an historic taking of water that allows Chicago to tap the lake for two billion gallons a day that’s never returned.

Very little of greater Chicago is in the Great Lakes basin , thus automatically entitled to draw from Lake Michigan. But the decision that allows the taking is codified by the Supreme Court.

Compare that to water-needy cities like Waukesha, Wis. that rest a few miles outside the basin dividing line but have to go through years of applications and approvals to take eight million gallons a day that will be returned.

Then there’s the Asian carp threat

The voracious fish that could wreak havoc on the lakes’ ecosystem is within striking distance of Lake Michigan with the Chicago Area Waterways System as the primary vector.

The ultimate way to stop the carp and other aquatic invasive species is to physically separate the Great Lakes from the Mississippi River. The Army Corps of Engineers has studied the issue and proclaimed that it’s feasible but time consuming and expensive.

“Not interested”, said Chicago and Illinois politicians, and they were supported by the Obama White House, which challenged legal attempts to close the locks leading to the lakes. They succeeded in court.

Many in the region saw that as Chicago and Illinois prioritizing their interests over that of the region of 30 million people, and that they were leveraging their clout with the president to do so. True or not, that’s how they saw it.

Meanwhile other cities haven’t been standing idly by while Chicago falters.

Detroit’s renaissance is progressing to the point that Detroit News columnist Daniel Howes last week opined that the Motor City may be able to rival Chicago as the business capital of the Midwest.

Howes cited the influx of companies like Microsoft and referenced Dan Gilbert who tells young job candidates they can go to Chicago and change nothing, or live and work in Detroit and make a difference. Gilbert is the Quicken Loans chairman who is heavily invested in reviving Detroit.

If Detroit could become the region’s business center, why not its water hub? If Great Lakes advocacy needs a new generation of leaders, could Detroit be the incubator?

It’s smack dab in the center of the Great Lakes region which connects the upper and lower lakes, and it borders Canada which shares responsibility for the Great Lakes. Plus, it’s a quick trip to the academic and research centers of Wayne State University, University of Michigan and Michigan State University.

Or Milwaukee

The beer city has been designated as a water technology hub and its Mayor, Tom Barrett, has invested in Great Lakes issues. Their efforts are supported by University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee’s Great Lakes Water Institute.

Between 2002 and 2008, as the Great Lakes intelligentsia was making the case for federal support, Chicago, with its girth and clout, was a natural for regional leadership.

But the political landscape has changed, and key executives have moved on.

Is now the time to examine Chicago’s role in Great Lakes leadership?