By Ellie Katz, Interlochen Public Radio

Points North is a biweekly podcast about the land, water and inhabitants of the Great Lakes.

This episode was shared here with permission from Interlochen Public Radio.

One morning, about a week before Christmas, Bill Vagts stepped outside to sweep some snow off his porch. And his little corgi, Darla, came with him. Within a matter of seconds, a black bear came running out from behind a parked car, pinned Darla to the ground and started biting.

Without thinking, Bill ran over to her, wrapped his arms around the bear’s neck and pulled it off. Darla escaped, but Bill was frozen there with a black bear in a headlock.

“He finally figured out that somebody, something, had him around the neck,” Bill said. “And then he turned and bit.”

Right in Bill’s stomach. Bill instantly let go of the bear and it took off down the road, where it attacked two more unsuspecting people.

The chances of being struck by lightning are higher than being attacked by a black bear. And this happened in the middle of winter, when bears are usually hibernating. So, what went wrong?

Credits:

Producer: Ellie Katz

Editor: Morgan Springer

Additional Editing: Michael Livingston, Dan Wanschura

Additional Production: Matthew Mikkelsen of Hayloft Audio

Music: Blue Dot Sessions

Transcript:

DAN WANSCHURA, HOST: One morning, about a week before Christmas, Bill Vagts steps outside to sweep some snow off his porch. And his little corgi, Darla, comes with him.

BILL VAGTS: I was headed out just to enjoy the morning, sort of. And of course, when I go out, she always wants to go with me, so–

WANSCHURA: So Darla runs out into the fenced yard, and wanders behind the car in the driveway.

Bill Vagts’ corgi, Darla. (Photo Credit: Bill Vagts)

VAGTS: I kind of was looking the other way, sweeping, and all of a sudden, she just bolted past me. … She was pretty hysterical.

WANSCHURA: Just barking loud and fast. Bill walks toward her, when all of a sudden, something hits his leg. A black bear runs right past him and jumps on Darla.

VAGTS: All that bear had in its brain was to get that dog and eat it. … And he was chewing on her stomach, and on her back, and it was at that point that I just reacted.

WANSCHURA: Bill had encountered black bears before; he lived in Isabella in the northwoods of Minnesota, near the Boundary Waters. But never something like this. Without thinking, he runs over to the bear, grabs its neck, and pulls it off Darla.

VAGTS: I shouldn’t have done that– total, total reflex reaction. … And Darla was still good enough to be able to run– get out of there and run off.

WANSCHURA: And then Bill is frozen there with a black bear in a headlock. And everything stands still for a moment. He’s not scared. He doesn’t think to let go. The only thing that crosses his mind is one random thought about the bear:

VAGTS: I looked down at his fur, and in my brain, for some reason, I went, “Boy, these bears are really black.”

WANSCHURA: And then the bear reacts.

VAGTS: He finally figured out that somebody, something, had him around the neck, and then he turned and bit.

WANSCHURA: Right in Bill’s stomach. Bill instantly lets go of the bear and turns away.

VAGTS: All I was thinking is get Darla up on the deck and get myself in the cabin. … And when I turned around, the bear had left. … He was just gone.

WANSCHURA: The bear had taken off toward another house… where it was about to find two more unsuspecting people. This is Points North, a podcast about the land, water and inhabitants of the Great Lakes. I’m Dan Wanschura.

That winter day in 2017, Bill Vagts was understandably preoccupied as he wrestled this bear. So he didn’t have time to question how weird it was. Why was this bear behaving so strangely, so aggressively, when the chances of being struck by lightning are higher than being attacked by a black bear? Today, we try to solve that mystery. Ellie Katz takes it from here.

ELLIE KATZ, BYLINE: A few houses down the road from Bill and Darla, two contractors are finishing up their morning coffee break. Dan Boedeker and Gary Jerich didn’t want to be recorded for this story. But I spoke to them on the phone.

The two guys are putting siding on a garage, when Dan sees something coming up behind Gary. At first he thinks it’s a big black dog. Here’s Dan – the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources interviewed him in 2017.

Dan Boedeker and Gary Jerich were putting siding on a garage when a bear attacked them. They swung a sawhorse, a level, a piece of siding, and finally, a shovel at the bear before finally getting a chance to escape to their van parked nearby. (Photo Credit: Minnesota Department of Natural Resources)

DAN BOEDEKER: I turned around and looked, and Gary was walking away from me, and this bear was on his ass, right on his ass. I mean, nose to ass, it’s right there.

KATZ: Dan starts yelling, “BEAR!” And Gary runs.

BOEDEKER: So he took off running, and the bear went running after him.

KATZ: The bear lunges at Gary, and Dan looks around for something to hit it with. He grabs a level and swings. He misses, but gets the bear’s attention. The bear turns to him. Dan slips and falls. And all of a sudden, he’s on the snowy ground, with a black bear on top of him.

BOEDEKER: I was kicking on him. I was laying on my back.

KATZ: The bear bites Dan’s knee, his foot. Gary is still on his feet pumping with adrenaline. He swings a piece of siding and misses. The bear sinks its teeth into Dan’s forearm. Gary swings a sawhorse and the bear turns back to him. As it comes towards him, Gary smacks it with a shovel as hard as he can. The bear falls down, dazed. And the two guys run to their work van nearby. The bear follows them as they back out of the driveway.

Dan and Gary made it to the hospital. Both of their clothes were torn up by the bear. Dan had several deep puncture wounds. He got 22 stitches in his right arm. He still has the scars, but he was OK.

He told me he was afraid of bear attacks for a while after that. He started carrying a gun; he’d look over his shoulder in the woods. Now, he recognizes it was a freak accident. And his last words in the interview with the conservation officer sum it up pretty well.

BOEDEKER: Never underestimate a bear.

Bill Vagts and his corgi, Darla, who both survived an attack from a black bear in Isabella, Minnesota in December 2017. (Photo Credit: Bill Vagts)

KATZ: While Dan was getting treated at the hospital, Gary went back to the scene with some conservation officers from the Minnesota DNR. The officers followed the bear’s tracks through the snow, until they found it alive about 250 yards away.

ANDY TRI: And they just found it lying on top of the snow. It was kind of curled up.

KATZ: This is Andy Tri. He’s a wildlife biologist at the Minnesota DNR. Gary’s smack with the shovel did some damage – the bear was clearly in a lot of pain. And the officers immediately shot and killed it. Andy actually wasn’t there but he got a phone call in the field telling him what had happened.

TRI: [It] just seemed like a crazy incident, to be perfectly frank. You know, bear attacks are so rare, it just seemed like a– like an odd thing.

KATZ: Since the 80s, there have only been about 15 unprovoked bear attacks that resulted in hospitalization in Minnesota.

TRI: Zero had happened in winter, as far as I’m aware.

KATZ: Andy did a quick examination of the bear’s body to see if anything might explain what happened.

TRI: You know, everything really seemed normal with this bear. At least from first appearances, it looked like a normal, healthy bear.

ELLIE KATZ: So you guys were stumped?

TRI: Truly. Truly stumped.

KATZ: So they sent the bear to a diagnostic lab where a vet could do a full necropsy — open the bear up and see what was going on. And what the vet found, Andy said he never would’ve predicted. That’s after the break.

KATZ: Dr. Anibal Armien spends most of his days looking at diseased animals. Like, truly any animal that’s ever been sick: dogs, geese, toads, bald eagles, bats, dolphins. So you’d think a veterinary pathologist like him might have a penchant for the morbid.

DR. ANIBAL ARMIEN: Maybe not actually. We love life. It’s just that we are kind of fascinated by how things got wrong.

KATZ: Armien was a vet pathologist at the University of Minnesota when the bear attack happened. And it was his job to autopsy this bear. The first thing everyone wanted to know was: Did this bear have rabies? And did the people it attacked need to get treated? It was the likeliest explanation for what happened.

ARMIEN: And that need[ed] to be ruled out, basically, as soon as possible.

KATZ: But the tests came back negative. Which led to the big question: What caused this bear to act so bizarrely? Was it habituated to humans? Was it sick? Armien looked around for any clues.

An initial examination of the bear’s body identified worn-down back claws, which are typically sharp on a wild bear, raising questions about whether the animal had been captive at some point. (Photo Credit: Minnesota Department of Natural Resources)

ARMIEN: Lungs, heart, gastrointestinal tract, liver, kidney.

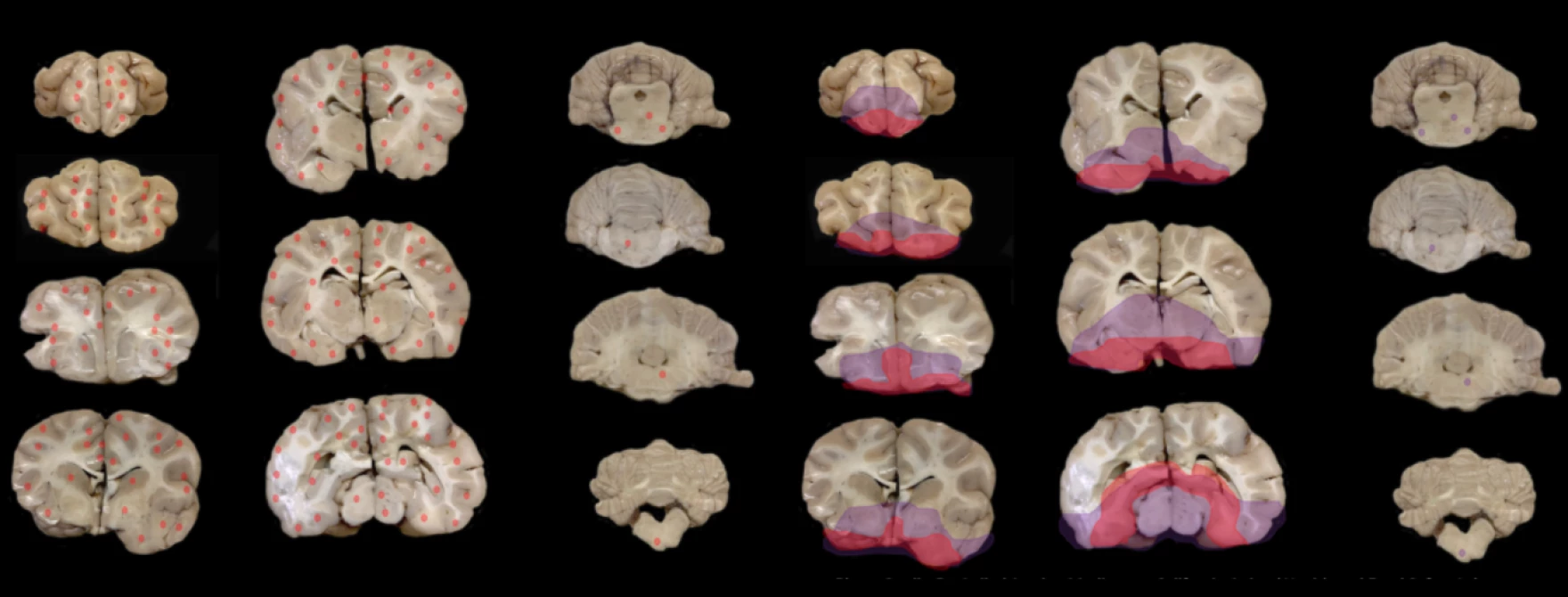

KATZ: Everything was normal. And then he got to the brain. This brain was not normal. It was inflamed — so inflamed that in some areas the brain had probably been pressing against the bear’s skull when it was alive. That brain inflammation is called encephalitis. In this case, it was probably caused by a herpesvirus.

ARMIEN: I was very surprised, because this type of encephalitis was never reported.

KATZ: To his knowledge, this was the first time this had been found in bears. And what Armien noticed was that the brain was inflamed in areas related to emotions, and memory, and circadian rhythms. That’s when things started to click: This could make the bear act in random ways.

ARMIEN: The area[s] that were affected in the brain, absolutely could bring the animal to an abnormal behavior. What is the abnormal behavior is not possible to predict. But based on the clinical history, or the history of the incident, we assume that the bear basically was not even reacting or responding as, like, a bear.

KATZ: That day in Isabella, Minnesota, the inflammation in the bear’s brain made it aggressive. The DNR and the public had their answers about the bear’s behavior. But we still didn’t know how this bear had gotten sick. A couple years later, Armien took a job as a pathologist at the University of California, Davis. And when he got there, he learned about something totally unexpected.

ARMIEN: And for my surprise, I came in and there was already concern about how bear[s] were presenting encephalitis in the state.

KATZ: The same thing he saw in Minnesota was happening in black bears in California and Nevada: brain inflammation, and bears acting not like bears usually act. Armien was stunned. The encephalitic bears out west would just walk right up to people, like a dog would. Like, there’s a video of a guy on a snowboard at a resort near Lake Tahoe. A small bear comes right up to him and starts sniffing his legs.

SNOWBOARDER: Coming back, Smokey? Sorry, dude. You see him bite my glove?

OTHER: Yeah.

SNOWBOARDER: Whatcha doin’?

Scans of black bear brains with encephalitis in California and Nevada. Researchers think protozoa and viruses are leading to brain inflammation, but no single cause has been identified. Affected bears are often one to two years old and exhibit “dog-like” behavior, like walking right up to people, along with muscle tremors, head tilts and seizures. (Photo Credit: Dr. Anibal Armien, California Animal Health & Food Safety Laboratory)

KATZ: Then it just waddles away looking disoriented and kind of unsteady. Sometimes other bears have muscle tremors, or drag their back feet. To try to explain how these bears got sick out west and in Minnesota, Armien and a number of other scientists have come up with a few different theories. And to understand those, we gotta zoom out a little bit. On the whole, black bears in North America are doing pretty well. Here’s Minnesota wildlife biologist Andy Tri again.

TRI: There’s more black bears now in North America than all other species of bears combined worldwide. They’re truly a conservation success story. We have bears in places we haven’t had for 200 years.

KATZ: But their habitat has changed. We’ve built roads, cut down trees for farmland. And instead of uninterrupted stretches of bear habitat, it’s patchier now, more fragmented. And because of all that, we’re living in closer proximity to bears. They’ll venture into farms, backyards and garbage cans for food. Which leads us to our first theory: this could help the spread of disease.

Armien thinks maybe pathogens from humans, and more importantly, our domestic animals, are making wildlife sicker. Andy, the biologist, sees some evidence of this in the bears he studies when he screens them for disease.

TRI: They’re showing exposure to distemper and exposure to rabies and exposure to toxoplasmosis.

KATZ: Canine distemper is a virus that we vaccinate dogs for. Toxoplasmosis is a parasite that often affects domestic cats. There’ve also been a handful of bears with bird flu, which often comes from domestic poultry flocks.

TRI: The only way they would be catching a lot of those things is through contact. … Without question, some of these diseases just didn’t occur in the wildlife populations prior to contact with humans and pets and that sort of thing.

KATZ: Another theory is that more bears squeezed into less space makes it easier for disease to spread.

ARMIEN: Many diseases, especially viral diseases, are favored by density.

KATZ: Which brings us to a third theory: Maybe bears are just more stressed out since they’re competing for less space and they’re living next to humans. Maybe that stress makes them more susceptible to disease.

And there’s other theories too. Like maybe these diseases have always existed in bears, and we’re just starting to notice. Or maybe there are just more diseases spreading amongst animals and humans in the world because of things like the exotic animal trade and climate change.

All of this leads us back to one big fat question: Do more sick animals mean more dangerous encounters with humans. Maybe? We don’t know that yet either. But the one thing everyone agrees on, is we are altering the world, and that’s affecting the health of wild animals. Armien, and others, argue one really good way to keep everything healthier is by protecting wild places.

ARMIEN: Basically the best form of defense for all of these problems, I will say, [is] conservation, preservation. … Wildlife have to have their own space where they can interact normally, free. And we have to respect that, yeah?

KATZ: Bill Vagts, the guy who wrestled the bear in Minnesota, is on board with that idea. His injuries from the bear attack were pretty minimal. He had two superficial puncture wounds from the bear’s teeth in his stomach. Same thing with Darla, his corgi, just on her back. And she’s still alive and well. Every once in a while, Bill thinks about what happened. But it doesn’t weigh on him too much.

VAGTS: It was never something that I was like, ‘Oh my gosh. You know, I could have been killed’ or anything like that. No, never. … I do know I’m very lucky.

KATZ: Bill didn’t see the bear again, except a photo of it after it was dead.

VAGTS: The bear, you know, was laying in the snow. He looked smaller, you know, lifeless. Yeah, sad, kind of.

KATZ: Yeah, why did it make you feel sad?

VAGTS: Well, I don’t– I just, you know, I’ve done, did a lot of hunting and fishing in my youth, and, you know, the older you get, the more you just like to see things alive.

KATZ: The northwoods were Bill’s home. But it was that bear’s home too. He wouldn’t change that.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Points North: Back to the Boundary Waters

Points North: A Sticky Solution for Microplastics

Featured image: After a black bear attacked three people and a dog in Isabella, Minnesota in December 2017, conservation officers tracked down the animal and killed it. Medical results later revealed it had a brain disease. (Photo Credit: Minnesota Department of Natural Resources)