Abdullatif Ahmed was just 23 years old when he first stepped foot on the Medusa Challenger, a 1906-built Great Lakes bulk freighter.

“Before I came to America in 1990,” he said, “I had never even seen the sea.”

Born and raised in Juban, a rural district in southern Yemen, Ahmed was drawn to the Great Lakes by family history and opportunity.

His grand-uncles and father, who came to the U.S. in the 1950s, worked on Great Lakes ships including the Ford Motor Company’s fleet, delivering raw materials from around the region to the massive Rouge plant in Dearborn.

“I wanted to be a sailor for two reasons,” he said. “I like water and as a sailor, at that time, you could save more money.”

Ahmed and his relatives aren’t alone. Records show Yemeni sailors working in the region as far back as the 1910s.

Back then the Great Lakes region was a hive of industrial activity.

Millions of laborers from around the world streamed into Detroit, Chicago, Milwaukee and elsewhere to work in automotive and other industrial plants.

Much of the economic activity in Detroit was fueled by manufacturers such as the Ford Motor Company, which owned iron ore and graphite mines in Wisconsin and in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan — materials essential in building its vehicles in Dearborn and Hamtramck.

In the 1920s, the company is believed to have faced a major problem: a lack of sailors to man the ships transporting raw materials south to Detroit.

In the 1800s, Yemeni seafarers were employed by the British navy in the Gulf of Aden and across the Indian Ocean. Although it has been difficult to verify, oral stories suggest that many who came to Detroit were reportedly sought out for their sailing skills and because of their abstinence from alcohol.

Later, waves of Yemeni immigrants who came to the U.S. in the 1950s and 1960s settled in Michigan to work in the Great Lakes shipping industry.

Today, around 30,000 people of Yemeni heritage are believed to live in Michigan, and Ahmed estimates that around 600 to 700 of those work on Great Lakes ships.

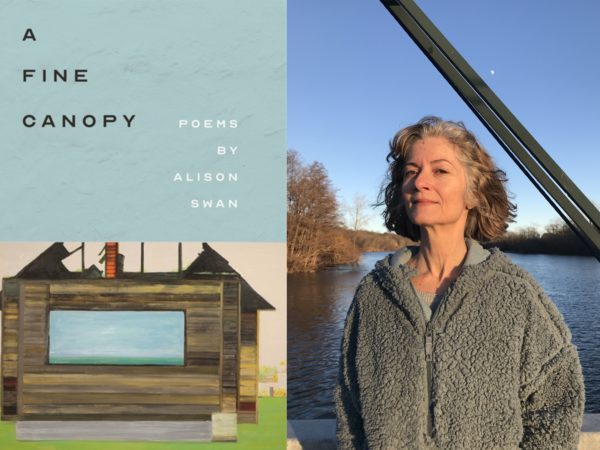

“I wanted to be a sailor for two reasons,” says Abdullatif Ahmed. “I like water and as a sailor, at that time, you could save more money.” (Photo Credit: Stephen Starr/Great Lakes Now)

“Now there are Yemeni captains, first mates, bosuns and [Yemenis in] other high-ranking positions,” he said.

Recording history

About 15 years ago, this little-known history of Yemeni Great Lakes sailors caught the attention of Professor Sally Howell, director of the Center for Arab American Studies at the University of Michigan-Dearborn.

“I had been running into Yemeni-Americans over the years and once I became aware that people’s parents worked on the Great Lakes, I became really curious about it, because there didn’t seem to be a record of this,” she said.

“Once I became aware of the history, it seemed like almost every Yemeni I talked to had somebody in their family who worked on the lakes. It was a much bigger story than I imagined, and it was a really important economic niche for this community.”

This prompted her to make the topic of Yemeni sailors a research project for her students in 2019, who set out to find and interview current and former sailors and ship workers. In total, 22 interviews were conducted, often by the sailors’ younger family members and in their own homes.

“A lot of people we interviewed, their fathers had come in the 1950s,” said Howell. “Especially when the auto industry began requiring a high school education [in the 1950s], a lot of men who were coming in that period were working on the lakes because [the shipping industry] didn’t have the same education requirements.”

In the interviews, the sailors speak of the pain of spending lengthy periods of time away from family, the monotony of life at sea, the back-breaking work of shuffling coal and working in ship “smokehouses” in the 1950s and 1960s. Others talk about how securing a position that included a private room was a goal as they could “pray my prayers and not worry about others.”

Professor Howell said what stood out to her was the skill level acquired by some of the Yemeni-American mariners.

“Some of the people we talked to become navigators,” she said. “There is one who is known [for his skill] guiding ships through the Detroit River, which is a challenging waterway. People have risen through the ranks.”

Another interesting observation, she said, was how it affected women in families whose fathers were absent for long periods. How some wives were empowered in the absence of their husbands.

In the past, many Yemeni-Americans chose to work on Great Lakes ships because the winter months saw shipping shut down, which offered extended periods of time off, allowing them to return to Yemen to see and support their families.

Today, however, most Yemeni sailors reside in southeast Michigan with their families.

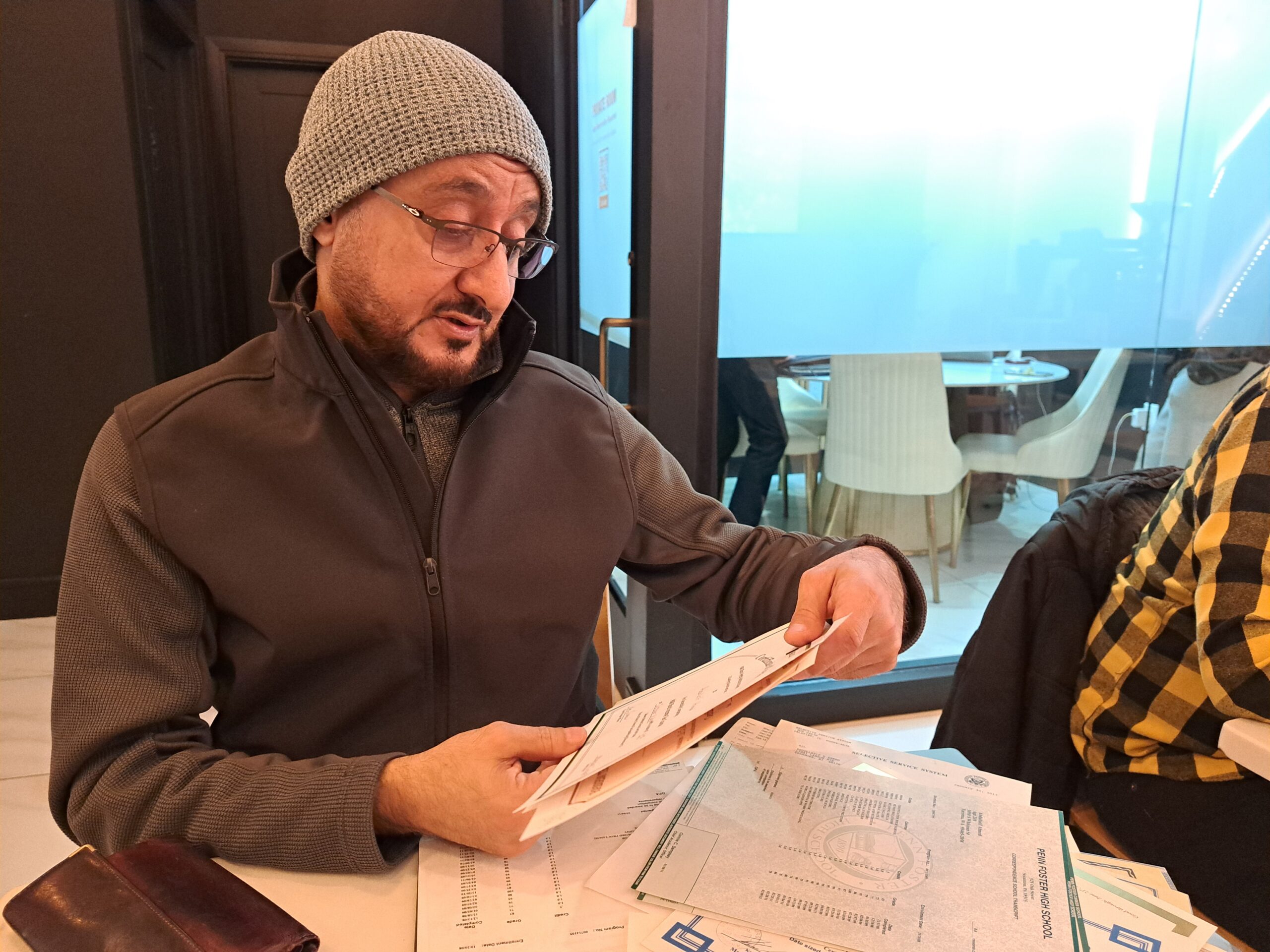

Dearborn is home to tens of thousands of Yemeni Americans such as Ahmed Abdullatif Ahmed who’ve spent their lives working on Great Lakes ships. (Photo Credit: Stephen Starr/Great Lakes Now)

Professor Howell said that several times the sailors, often in their 70s and 80s, came to her classes to listen to the student presentations.

The oral histories, which include photos and video footage of life on the frozen Great Lakes, were deemed to be of such importance that the work is now housed as a Digital Special Collection at the Arab American National Museum (AANM) in Dearborn.

“We’re happy to have these donated oral histories. It ties in with speaking about this recent immigrant community that we have in Dearborn and Detroit, this was their experience as a way of coming into the US,” said Shatha Najim, Community Historian at the AANM and who transcribed several of the interviews.

“It’s an important story to tell to create a complete picture of who is in Dearborn, Detroit and the surrounding areas,” says Shatha Najim, Community Historian at the Arab American National Museum. (Photo Credit: Stephen Starr/Great Lakes Now)

“A lot of people were also doing this back in Yemen, it was passed down in the family. It’s an important story to tell to create a complete picture of who is in Dearborn, Detroit and the surrounding areas. I’m really glad this project started and was done in such an authentic way.”

Central to Great Lakes life

At the Dossin Great Lakes Museum on Belle Island in Detroit, the role Yemeni and Arab sailors have played in the history of Great Lakes shipping is honored in a small way.

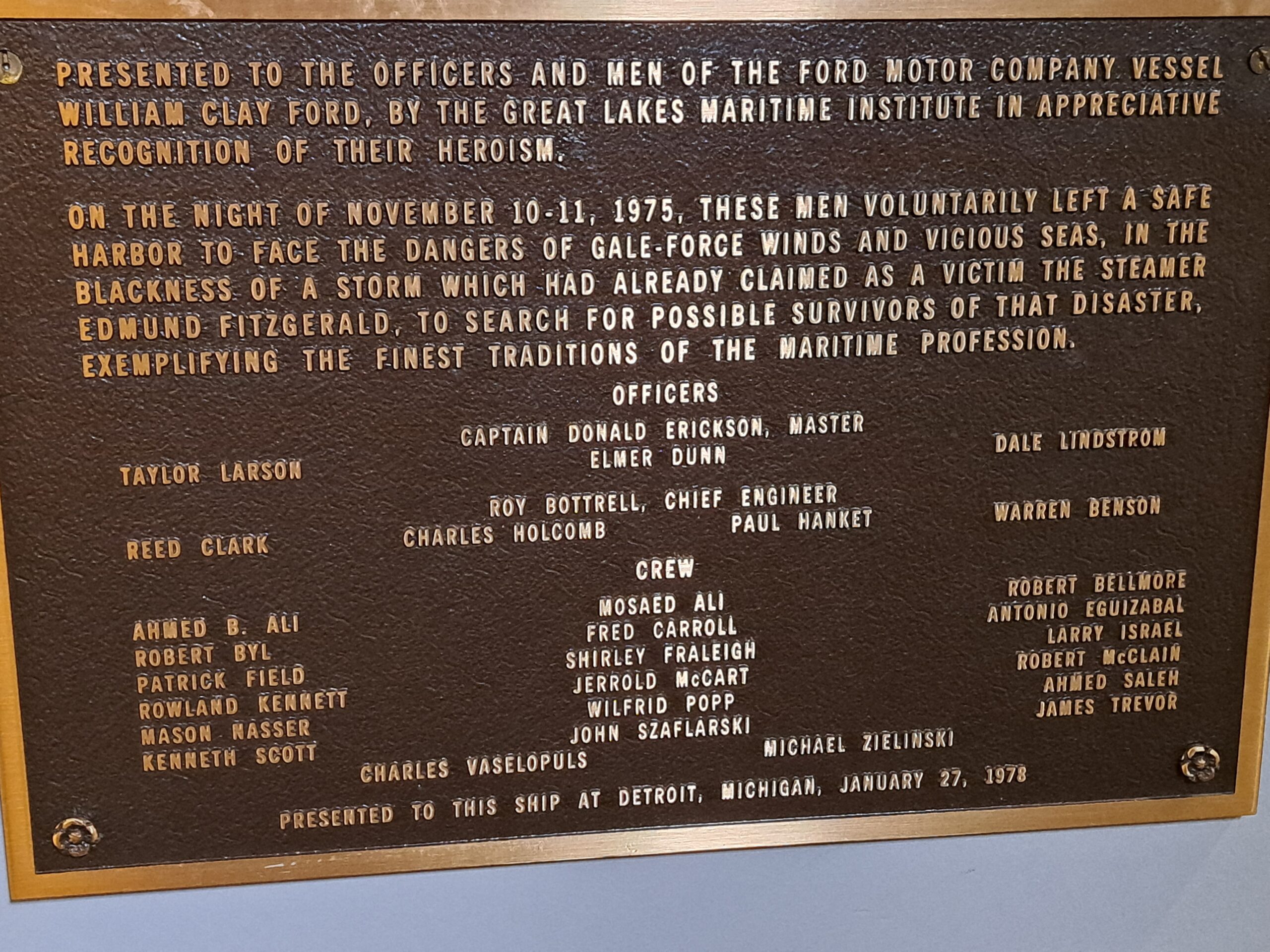

The museum contains the cabin house of the SS William Clay Ford, a bulk freighter.

Inside the ship’s pilot house is a dedication to its sailors, who on November 10, 1973 “voluntarily left a safe harbor to face the dangers of gale-force winds and vicious seas, in the blackness of a storm … to search for possible survivors of that disaster, exemplifying the finest traditions of the maritime profession.”

The “disaster” is in reference to the SS Edmund Fitzgerald, which went down northwest of Lake Superior’s Whitefish Bay with the loss of all on board in one of the worst tragedies in recorded Great Lakes maritime history.

The dedication bears the names of Ahmed B Ali and Mosaed Ali — Arab and Yemeni-American sailors who served on the ship that night.

A plaque in the SS William Clay Ford depicts the names of several Arab and Yemeni Americans who risked their lives to find survivors from the SS Edmund Fitzgerald. (Photo Credit: Stephen Starr/Great Lakes Now)

Illustrating the close-knit nature of seafaring life on the Great Lakes, upon seeing one of the names in a photo of the dedication, Abdullatif Ahmed’s face lights up.

“I know Mosaed Ali; he was my mother’s uncle,” he said. “I’m sure [it is him], because he was a well-known name in the community. One hundred per cent.”

Cold, ice and danger

Ahmed said one of the most difficult jobs he encountered on the Great Lakes involved using a bosun chair when working as a deckhand.

The bosun chair was made to go paint or do other jobs hanging off the side of the ship. According to Ahmed, it was often the only way to get to certain hard-to-reach spots. However, the bosun chair wasn’t the only dangerous part of the job.

“First, the Great Lakes weather is very much worse than the deep sea,” Ahmed said. “I’m not talking about waves or the swell, I’m talking about the cold, ice and danger.”

He said on one occasion his ship was stuck by ice on Lake Superior for three days.

But the worst was docking a ship at night, in the cold at a location where there was no dock crew to help.

“That meant that you had to swing off the ship onto the dock and tether the ship to the dock,” he said. “Doing that with snow and ice … Then you had to clean down the deck of the ship — you’re talking about an 800-foot-long ship. In the cold, the water on the steel would turn to ice quickly and you could slip.”

“You needed some heart to do that.”

After leaving the Medusa Challenger, which was later renamed the SS St. Marys Challenger, Ahmed worked on other ships, and for the Buffalo-headquartered American Steamship Company, transporting grain from ports in western Lake Superior to Toledo, Cleveland and Buffalo.

He eventually rose to the rank of third mate — a vessel’s safety officer — and worked on ships around the world, visiting North Korea, Hawaii and the Middle East.

He left shipping a decade ago when the demands of family life grew.

“We had four kids at home, my wife did not speak English, and she had to deal with all the things when I was away: doctors, school, driving around,” he said.

“There was nobody here to take care of them.”

But he said there are upsides to life on the lakes such as having extended periods of time off when ports around the lakes froze over, which allowed travel back to Yemen. And unlike deep sea sailing, he said, where employment contracts often lasted only several months, on the Great Lakes you still had a job when you returned from time off.

Yemeni ship workers have added their touch to life on the lakes. Those working in the kitchen regularly prepare Middle Eastern dishes such as hummus, tabbouleh salads, lamb kabobs and baklava.

On the whole, Ahmed said that his religious requirements that meant fasting during daylight hours during the Islamic month of Ramadan or eating halal food were well-respected.

“Sometimes we had a Yemeni cook who knew [what our dietary requirements were]. Sometimes we have very nice people who would tell you what was pork,” he said. “Eighty or 90 percent of the ships knew.”

While Ahmed has left his seafaring days behind, the regular sight of ships and tugboats on Dearborn’s Rouge River serve as a constant reminder of his past life.

“The fresh air you can breathe in,” he said, reminiscing of his days on the open water. “It’s just different to life in the city.”

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Cargo tonnage lagging at Great Lakes ports as shipping season nears its end

Great Lakes Moment: Michigan’s Port of Monroe fosters a blue economy that welcomes wildlife

Featured image: Ships on Dearborn’s Rouge River are a constant reminder for local seafarers of their connection to the Great Lakes. (Photo Credit: Stephen Starr/Great Lakes Now)