Great Lakes Fact or Fake? is a new book by Dave Dempsey. Below are adapted excerpts from the book, which bring readers along while he answers 41 myths about the Great Lakes.

Drinking Sewage

FACT or FAKE?

There was a time when many people in the Great Lakes watershed drank sewage.

With some highly publicized exceptions like the disastrous lead contamination of the Flint, Michigan, water supply in 2014 and the Benton Harbor, Michigan, water supply that prompted action in 2022, today’s public tap water in the Great Lakes region generally meets health standards. To be sure that the drinking water piped to households is free of harmful microorganisms, utilities apply chlorine, sometimes changing the taste of the water.

Chlorination was not widely used until the 1920s. This would have mattered less if municipal sewage discharges had not flowed downstream toward public drinking water intakes. But they often did, and the results were disease and death. In 1918, the International Joint Commission reported on the condition of the boundary waters between the two countries with an emphasis on the connecting waters of the Great Lakes. The IJC concluded that drinking water safeguards in those areas were a disgrace.

Contamination of surface waters used for municipal systems was fatal to thousands of people. Many communities at that time drew drinking water from rivers into which upstream communities dumped untreated sewage. Typhoid and cholera outbreaks were common. The boundary waters studied by the IJC in 1918 included the St. Marys, St. Clair, Detroit and Niagara rivers. The study found that the water supply of Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, was foul, adding, “Acute outbreaks of typhoid must always be expected from the use of such seriously polluted water.”

The Niagara’s problems were also dire. Although some people believed churning water below Niagara Falls dissipated sewage, “It simply mixes it more thoroughly with the water; it does not remove it or its danger. The pollution below the Falls is gross.”

The St. Clair River was too polluted for drinking without extensive treatment for 34 miles south of Port Huron, Michigan, and Sarnia, Ontario. Even worse was the Detroit River. “From Fighting Island to the mouth of the river the water is grossly polluted and totally unfit as a source of water supply… Unfortunately, Wyandotte, Trenton and Amherstburg are taking their water supplies from this part of the river,” the Commission concluded.

The Commission also compiled health statistics from communities relying on the waterways for drinking water, including Port Huron, St. Clair, Marine City, Algonac, Detroit, River Rouge, Ecorse, Wyandotte and Trenton. The results were striking: typhoid fever death rates were highest in cities whose community water supplies were drawn from the foulest water. In Port Huron, 33 people died from typhoid fever from January to July 1912 before chlorine was applied.

Things were barely better on the Canadian side, the Commission found. Walkerville and Windsor were in “dangerous situations” with sewage being discharged upstream of their drinking water intakes.

Those on land weren’t the only victims. In 1907, a steamer traveling the Great Lakes pulled drinking water from the Detroit River, resulting in 77 cases of typhoid fever. In 1913, on three Great Lakes vessels carrying 750 people, there were 300 cases of diarrhea, 52 cases of typhoid and seven deaths.

The report helped spur governments along the border, including Detroit and downstream communities, to chlorinate drinking water supplies and save lives. But the City of Chicago had a different solution. Its drinking water came from Lake Michigan, the same place where its sewage went. To reduce death and disease, the city engineered a reversal of the Chicago River, which had flowed into Lake Michigan. In 1900, the river began flowing west toward the Illinois River and away from the lake, taking Chicago’s sewage with it.

Over the decades, further advances in drinking water treatment have virtually wiped out typhoid and cholera linked to public water supplies. There was a time when many people in the Great Lakes watershed drank sewage.

FACT

Salt and Shark-Free

FACT or FAKE?

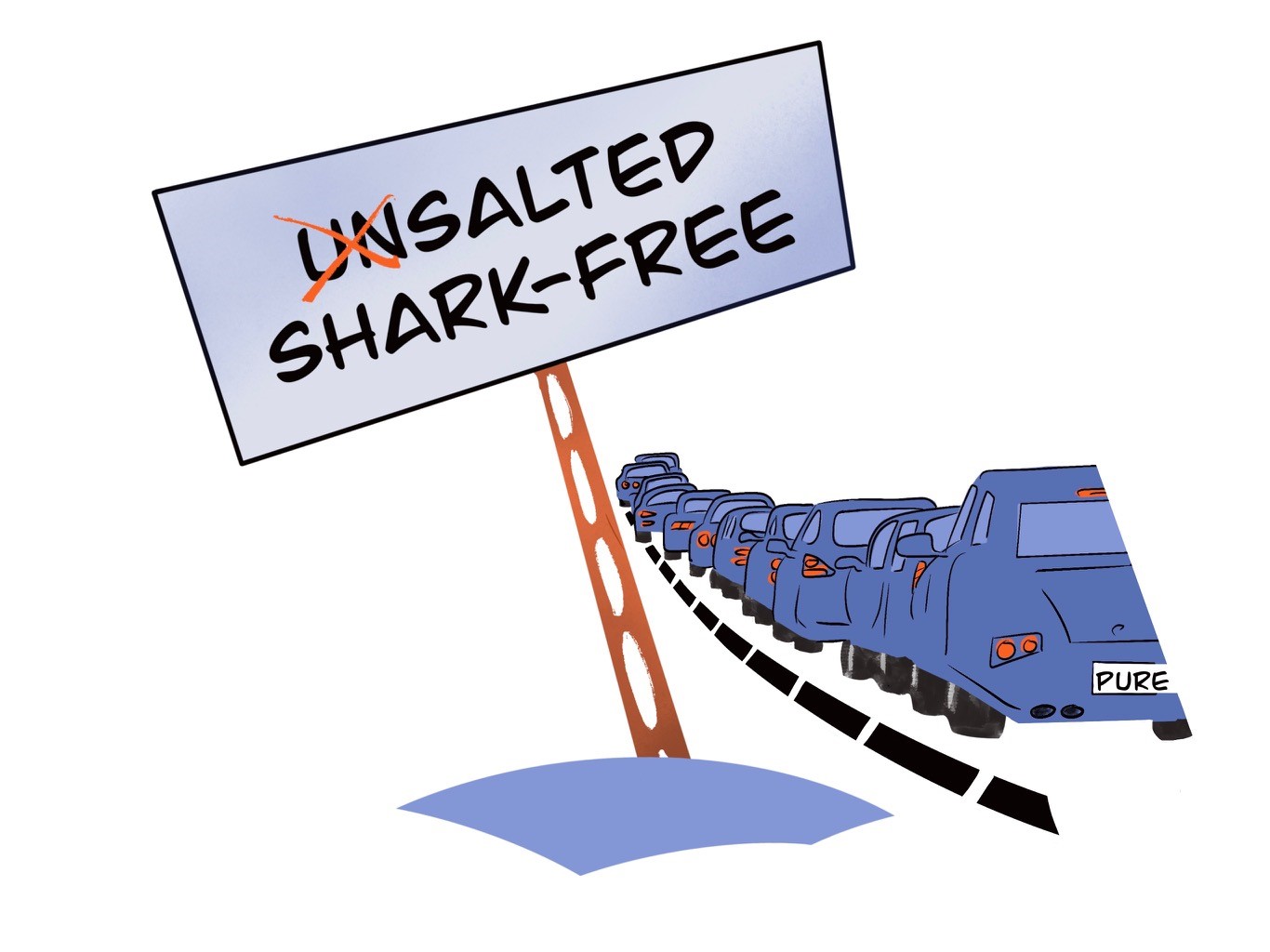

The Great Lakes are “Unsalted and Shark-free,” as a vehicle decal popular in the region proudly declares.

Some residents of the Great Lakes region, proud of their freshwater heritage, celebrate that identity with signs, personalized license plates, and decals. One decal commanding attention declares that the Great Lakes are unsalted and shark-free, and we’ve already seen that whales don’t inhabit their waters. No sober sightings of sharks have been confirmed, but are the Great Lakes unsalted?

Not if you consider road salt and salt from water softeners, they’re not. In 2021, researchers estimated chlorides in Lake Michigan had risen from about 1 to 2 milligrams per liter before European settlement to more than 15 milligrams per liter. Canadian researchers found levels ranging from 1.4 milligrams in Lake Superior to 133 milligrams per liter in Lake Ontario. Although these levels are well below the chloride concentrations in ocean water, about 35 grams per liter, and below the aesthetic standard for chlorides in drinking water, about 250 milligrams per liter, rising concentrations may have biological impacts.

These include killing or otherwise harming aquatic plants and invertebrates.

The Lake Michigan salinity level studies found that watersheds with a greater surface area of roads, parking lots and other impervious surfaces tended to have higher chloride levels due to direct runoff into streams and lakes.

Although road salt is likely the largest source of chloride pollution of the Great Lakes, livestock, fertilizer, and water softeners also contribute. Still, the simplest solution to rising chloride levels in the Great Lakes is to use less road salt, and transportation officials have sought ways to apply less salt on roads during winter while keeping roads clear and safe for motorists. The most direct way is to put salt on fewer roads. In some cases, sand or ash is used as an alternative in lower-traffic areas.

As for sharks, well, there was a report of a bite taken out of a Chicago-area man by a bull shark on Jan. 1, 1955. The best guess of the Chicago Tribune is that it was a hoax published in 1975, the year the movie Jaws was released. So “shark-free” is accurate.

The Great Lakes are “Unsalted and Shark-free,” as a vehicle decal popular in the region proudly declares.

FAKE

Only half right, the half involving sharks.

Abe and Asian Carp

FACT or FAKE?

A Great Lakes policy that threatens its fishery can be traced to Abraham Lincoln.

Just before the rise of the railroads, America teemed with proposals to link areas of the United States with canals. The aim was to connect farms and business with markets. Opening for business in 1825, New York’s Erie Canal provided a much shorter and cheaper route for commodities to flow from the Great Lakes to the Atlantic coast. Its success spawned imitators. The Great Lakes states caught the fever.

- Completed in 1832, the Ohio and Erie Canal connected Akron to the Cuyahoga River and Lake Erie in Cleveland. Later, it connected with the Ohio River near Portsmouth.

- Not completed until 1876, Wisconsin’s Portage Canal connected the Fox River and Wisconsin River at Portage, Wisconsin, but was not economically competitive with railroads at that late date.

- Michigan’s Clinton–Kalamazoo Canal was abandoned after only 13 miles of a proposed 216-mile route was completed. A nationwide financial panic dried up funding for the project, whose purpose was to connect Lake St. Clair with Lake Michigan, cutting hundreds of miles off the conventional route around the Straits of Mackinac at the tip of Michigan’s Lower Peninsula.

Connecting waterways for commerce made sense in the era before environmental impact statements. Environmental concerns were irrelevant to such projects. It is possible the sea lamprey reached the upper Great Lakes via the Erie Canal. Meanwhile, visions of expanding commerce spurred yet another canal, and future U.S. President Abraham Lincoln was a proponent. The Illinois and Michigan Canal would provide a trade shortcut, this time hitching the Great Lakes to the Mississippi River. State Representative Lincoln and fellow legislators from Sangamon County won support for the canal as part of a political deal. In 1848, the 96-mile canal was completed. Lincoln probably traveled on the canal on more than one occasion between 1848 and 1852. During his only term in Congress, Lincoln gave a floor speech in the House of Representatives heralding the opening of the waterway.

The Illinois and Michigan Canal in a sense fathered the much bigger connection of the Chicago River to the Illinois River completed in 1900. The latter’s primary purpose was the shunting of sewage away from the Lake Michigan drinking water intakes of the city of Chicago. But the connection also had a commercial purpose: increasing trade between the Great Lakes and Mississippi River systems. Today, the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal is the route by which three species of Asian carp are moving northeast toward Lake Michigan. Although it is unclear what impact Asian carp in the Great Lakes would have, fishery biologists worry that the carp’s foothold could be disastrous, as the invader fish compete with fish species for food and habitat, and carry diseases or parasites that could spread to native fishes. Asian carp grow large very quickly and native Great Lakes predators would be unlikely to control them, as they would quickly outgrow the gape (mouth) size of native species.

As of 2021, state and federal governments had spent nearly $607 million to stop the fish since 2004. Projected costs were about $1.5 billion over the next 10 years. Without the advocacy of Lincoln and legislative colleagues, the need to spend this money may never have materialized.

As a side note, Lincoln took at least one Great Lakes trip that resulted in rapture at the beauty of Niagara Falls and in the only U.S. patent awarded a future, current, or past president.

After seeing the falls in the autumn of 1848, Lincoln mused, “By what mysterious power is it that millions and millions are drawn from all parts of the world to gaze upon Niagara Falls! There is no mystery about the thing itself. Every effect is just such as any intelligent man, knowing the causes would anticipate, without seeing it. If the water, moving onward in a great river reaches a point where there is a perpendicular jog of a hundred feet in descent in the bottom of the river it is plain the water will have a violent and continuous plunge at that point.”

On the same trip, Lincoln’s passenger vessel cruised up the Detroit River. Lincoln observed the crew of a steamer that had run aground wedge empty casks and barrels under the vessel’s gunwales to increase its buoyancy. This gave Lincoln an idea that he patented the next year. Lincoln’s concept was to use sacks inflated by bellows carried by a grounded vessel to provide it with buoyancy. He got the patent but made no profit.

Meanwhile, Lincoln’s brainchild, a canal linking Lake Michigan to the Illinois River, continues to vex Great Lakes sport fishing interests. A Great Lakes policy that threatens its fishery can be traced to Abraham Lincoln.

FACT

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Invasive Species Control in the North American Great Lakes

Storied Two Hearted River gets 21st century update in new book

Featured image: Are the Great Lakes unsalted? (Photo Illustration by Heather Shaw)