By Matt McIntosh

The Great Lakes News Collaborative includes Bridge Michigan, Circle of Blue, Great Lakes Now at Detroit PBS, Michigan Public and who work together to bring audiences news and information about the impact of climate change, pollution, and aging infrastructure on the Great Lakes and drinking water. This independent journalism is supported by the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation. Find all the work HERE.

From the window of a fishing boat, Andrew Taves has a clear view of how Lake Erie is changing. He’s been a commercial fisherman for just shy of seven years in Wheatley, Ont., which claims to be the largest freshwater commercial fishing port in the world.

Taves and his crewmates set nets primarily for the most valuable and sought-after fish — yellow perch and pickerel — as well as a couple other species of lesser value. Sometimes they catch lamprey, gobies and other invasive fish, as well as significant quantities of low-value shad — a species that’s supposed to largely die off in winter, but which Taves suspects has proliferated due to warmer winter water temperatures.

Fishermen in Wheatley, Ont., the largest commercial freshwater fishing port in the world, start early in in the morning. The presence of invasive grass carp in the lake system threatens the local environment and economy. (Photo Credit: Andrew Taves/The Narwhal)

Taves has yet to find grass carp in his crew’s nets, but it could be just a matter of time.

The invasive fish have been caught off the coast of nearby Point Pelee National Park, Rondeau Provincial Park and elsewhere in Canadian waters. There are breeding populations of grass carp on the American side of Lake Erie. But collaboration between American and Canadian governments, research institutions and local communities have kept the species from gaining a strategic foothold.

The massive freshwater system is no stranger to invasive species, but grass carp could upend the Great Lakes ecology, as well as the operations of some of the world’s most significant freshwater commercial fisheries. So far, the Great Lakes have successfully held grass carp at bay. Those involved in managing the grass carp — not to mention the fishermen who rely on the abundance of native fish — can only hope that success is sustainable.

Yellow perch and pickerel are by far the most sought-after species by Lake Erie commercial fishermen. They also catch a variety of lesser value, and often invasive, species. (Photo Credit: Andrew Taves/The Narwhal)

What are Asian carp?

Grass carp are one of four similar fish species known as Asian carp that originate in Eurasian rivers: grass, silver, big head and black carp. Each species has unique characteristics, but they can all get very big — up to 40 kilograms — and all four species are prolific eaters. Each day, carp can consume between five and ten per cent of their body weight in microscopic plant and animal life (phytoplankton and zooplankton). Grass carp also eat rooted aquatic plants. This feeding behaviour can devastate threatened wetland environments, and the fish that rely on them for spawning and nursery activities.

Grass and other Asian carp were imported to the United States in the 1970s as a biological method of cleaning ponds. Through flood events, dumping and other means, some eventually escaped their ponds to American lakes and rivers. There, they thrived.

With no natural predators, these species have successfully outcompeted native fish in waterways across vast swaths of the United States, most notably in parts of the Mississippi River and its tributaries. Asian carp are estimated to comprise as much as 80 per cent of all aquatic biomass in some places, wreaking havoc on local biodiversity. The economic hit to both commercial and recreational fishing has also been profound.

Staff with the Ohio Department of Natural Resources are a part of a cross-border effort to catch grass carp and keep them from establishing themselves in the Great Lakes. (Photo courtesy of the Ohio Department of Natural Resources)

Since 2007, it has been illegal to import live Asian carp to American states bordering the Great Lakes. Importing live fish to Ontario is also prohibited, but eviscerated fish can be brought in for the food market. Live imports in other parts of the United States are still permitted, as long as the fish are rendered infertile through a treatment applied when they’re newly hatched.

But whether by ineffective treatment or illegal importation, the Great Lakes region now faces a constant threat of Asian carp entering its wider ecosystem. Thus far, barriers between the Great Lakes and Mississippi basins have kept them at bay, except for grass carp — the only Asian carp species found in the Great Lakes in any significant number to date.

Grass carp make their Lake Erie debut

Chris Mayer, a professor at the Lake Erie Centre at the University of Toledo, Ohio, is a veteran in the study and control of grass carp in Lake Erie and its tributaries. Speaking to journalists and fishing charter captains at Ohio State University’s Stone Laboratory in August 2024, Mayer said grass carp have been identified in Lake Erie watersheds in small numbers since the 1980s. However, they were largely infertile, and spurred little concern.

But in 2012, fertile grass carp were first identified near the mouth of Ohio’s Sandusky River, which opens into a bay of Lake Erie. The finding indicated some breeding populations had likely established themselves in parts of the Great Lakes system. This hypothesis was confirmed when, in 2015, grass carp eggs were found in the Sandusky River. In response, an inter-state surveillance and control effort began in 2017.

“There aren’t any, or many fish that eat plants that are rooted to the bottom … This is a very unusual thing. They are very good at it, and can get very big,” Mayer said. “Our state is spending money to construct and connect wetlands to the lake. We don’t want to have this herbivore wiping out the vegetation that does good things for water quality, and provides good habitat for juvenile fish of other species.”

In 2015, grass carp eggs were found in the Sandusky River, putting the Ohio Department of Natural Resources on high alert. Crews from the department are seen here in 2018 seeking out the invasive fish. (Photo courtesy of the Ohio Department of Natural Resources)

David Marson, manager of Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s aquatic invasive species program, described grass carp as “machines for feeding on vegetation” that can actually consume up to 40 per cent of their weight in rooted aquatic plants daily.

“If we had a breeding population get into Rondeau Bay or Long Point — those are highly productive, highly valuable resources for a lot of our native fish species for spawning or fish rearing habitat, or other waterfowl and things as well. We don’t want these fish getting in there and consuming a lot of that vegetation,” Marson told The Narwhal.

In her August presentation, Mayer was even more blunt about the current situation: “With grass carp, we are past prevention because they are here. We’re in the stage of eradication or containment.”

Gone fishing: catching grass carp is easier said than done

Mayer, Marson and many others across a wide range of political, institutional and community borders have collaborated under the Great Lakes Fishery Commission to seek and destroy grass carp wherever they are found.

The Americans maintain a constant force of people monitoring for the fish and their eggs, with a network of rapid-response fishing crews. In Ontario, Marson said four crews are employed full-time through the summer, with reduced operations the rest of the year. There are also separate “larval crews” for monitoring eggs in at-risk waterways, as well as multi-species monitoring crews in the St. Lawrence River. Indigenous partners help monitor remote areas such as northern Lake Huron. The Ontario government also co-operates in sampling.

Currently, an average of 150 to 200 grass carp on the American side of Lake Erie are caught each year. On the Canadian side, Marson said 33 have been caught since 2012. Most of these have been infertile — but not all.

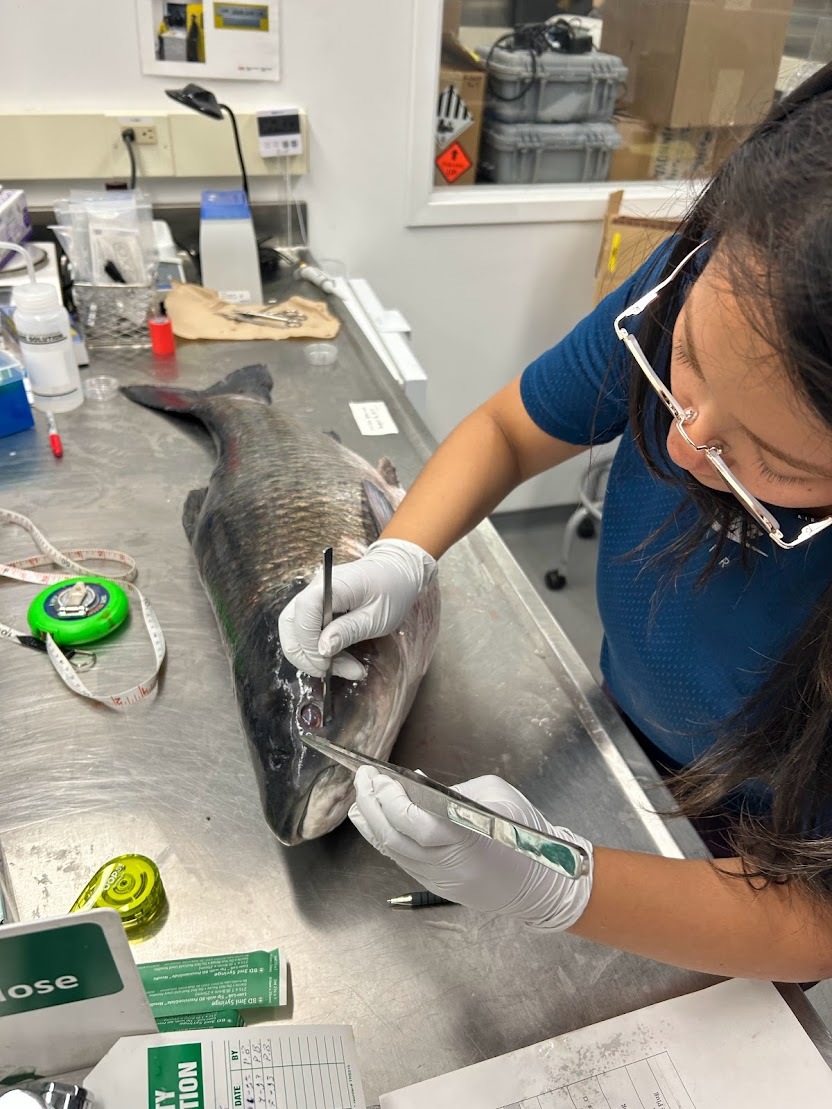

Biologist Trisiah Tugade samples a grass carp to determine whether or not it’s fertile. It is illegal to bring live grass carp into Ontario, whereas parts of the U.S. allow live imports as long as they’re rendered sterile. (Photo courtesy of Fisheries and Oceans Canada)

A range of methods are used to catch grass carp, including different types of nets and electrofishing — using electricity to stun fish to the surface, where they can be collected and euthanized. Captured fish are brought to laboratories and analyzed for age, fertility and other biological indicators.

Recreational anglers who catch grass carp also provide opportunities for concerted eradication efforts. Marson related one instance, where a fisherman on Lake Gibson, in Niagara, Ont., thought he landed a once-in-a-lifetime lunker, as an example why public awareness campaigns also comprise part of the cross-border control strategy.

“It was his birthday, and he was like ‘Look how lucky I was to catch this!’ — and released it. But we were able to track them down. They didn’t do anything wrong. They didn’t realize what they had. So, we approached them, figured out where it was and went out with our crews … It wasn’t just one fish, it turned out to be ten fish we removed from there,” Marson said.

Mayer said determining the best fishing methods and times of year to capture grass carp is an ongoing challenge. And some areas are very hard to reach, making regular analysis a challenge. Current fishing methods are also best suited to catch grass carp that are at least four years old, while sexual maturity occurs at three years.

“They get a year of reproduction in before our methods are kicking in … But it’s better to know we have this problem,” Mayer said. She added their analysis of captured grass carp indicates average maturity is rising over time. Fewer young fish in the population mix suggests the control efforts are having an effect in limiting reproduction.

A trail along the shore of Erieau, Ont., a village on the southwestern point of Rondeau Bay on Lake Erie. Individual grass carp have been caught in this area, but so far no breeding populations are known to have established. (Photo Credit: Matt McIntosh/The Narwhal)

Cautious optimism about keeping grass carp at bay

In Canadian waters, Marson said there’s been no detection of grass carp breeding.

If grass carp were filling fishing boats every time they launched, or leaping out of the water en masse as other species of Asian carp do in the Mississippi River, Mayer said, “the horse [would be] out of the barn.” Thankfully, this has not come to fruition.

But the risk of grass carp getting out of hand is still real, however, as is the risk posed by the other three Asian carp species.

“It wouldn’t take a long time. We would only need ten males and ten females, and that would be sufficient to really lead us down the road to an invasion,” Marson said.

For fishermen like Andrew Taves, it’s a very real threat that could make it challenging to earn a living on the Great Lakes.

“We already have invasive species, pollution, climate change,” Taves said. “We don’t need this.”

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

4 things to know about a youth-led court case against Ontario’s climate plans

Two high school students want to keep trash out of the Great Lakes. They think rivers are the key

Featured image: On the Bay of Quinte, on Lake Ontario, crews with Fisheries and Oceans Canada, along with partners in the U.S., keep a watchful eye for grass carp. Breeding populations of the invasive fish have been found on the American side of Lake Erie, and could devastate the Great Lakes ecosystem. (Photo courtesy of Fisheries and Oceans Canada)