Points North is a biweekly podcast about the land, water and inhabitants of the Great Lakes.

This episode was shared here with permission from Interlochen Public Radio.

Theresa Eischen would visit her grandparents every summer. They lived on a remote First Nations reservation in Canada. One of her favorite memories was their epic movie nights.

“I think they were the only family in Little Grand Rapids that owned a film projector,” remembers Theresa.

Grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins would all pile into one of the small houses on the reservation. They’d cover the windows with towels or sheets to make the living room dark.

“I remember sitting down with her and watching movies that were very entertaining,” she said. “But I wasn’t sure of how much she actually understood of the movie.”

That’s because Theresa’s grandma didn’t speak English. She’s Ojibwe and spoke Anishinaabemowin – the endangered indigenous language of the Great Lakes region.

Theresa dreamed of the day her grandma could watch a film in her own language.

Then last December, when Theresa heard about the original Star Wars film being translated into Anishinaabemowin, she auditioned for Princess Leia. But she had zero voice acting experience, so it was a long shot.

CREDITS:

Producer / Host: Dan Wanschura

Editor: Morgan Springer

Additional Editing: Ellie Katz

Music: Blue Dot Sessions

Special Thanks: Cary Miller, Sabrina Ortiz, Anton Treuer

TRANSCRIPT:

DAN WANSCHURA, BYLINE: This is Points North. A podcast about the land, water, and inhabitants of the Great Lakes. I’m Dan Wanschura.

When she was a kid, Theresa Eischen loved visiting her grandparents. Every summer, she’d get in a small float plane and fly to this super remote place called Little Grand Rapids in Canada. It’s a First Nations reservation near the Manitoba–Ontario border. The only time you can drive there is on a winter road across frozen lakes.

One thing that stands out in Theresa’s memory from those visits are the epic movie nights … put on by her grandparents.

THERESA EISCHEN: I think they were the only family in Little Grand Rapids that owned a film projector.

WANSCHURA: Grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins – would all pile into one of the small houses on the reservation.

EISCHEN: And they would cover all the windows with sheets or towels to make it dark in the living room. And they would … put a sheet on the wall and they would … have to order these movies through the mail to get the film.

(sounds of horses and gunshots)

WANSCHURA: Westerns with stars like Gene Autry, Roy Rogers, John Wayne.

(John Wayne movie clip)

EISCHEN: I remember sitting down with her and watching movies that were very entertaining. But I wasn’t sure of how much she actually understood of the movie.

WANSCHURA: That’s because Theresa’s grandma didn’t speak English. She’s Ojibwe and spoke Anishinaabemowin – the indigenous language of the Great Lakes region. It’s an endangered language – as older people pass away, fewer and fewer people speak it.

But still, Theresa dreamed of the day her grandma could watch a film in Anishinaabemowin. The story of what happens with that dreaming – coming up right after the break.

(sponsor messages)

WANSCHURA: There’s something else you gotta know about Theresa Eischen. As a kid, she didn’t speak Anishinaabemowin. She’s from a mixed race family. Her dad is white and her mom is Ojibwe. They raised their kids outside Winnipeg, Manitoba, in a mostly white area.

So, Theresa grew up speaking English. Which meant when she visited her mom’s family on the remote reservation in Little Grand Rapids, she couldn’t have a conversation with her grandma – the woman she’s named after.

EISCHEN: My grandma, she was so dear and she was so gentle, and she helped me a lot because she would use hand gestures and pointing to things as well when I was around her.

WANSCHURA: But Theresa wanted more.

EISCHEN: I was probably about five years old when I recognized that. … I said to my mom, ‘I want to learn the language. … I want to be able to communicate with my grandmother.’

WANSCHURA: Throughout her childhood, Theresa slowly picked up bits and pieces of Anishinaabemowin. But she still wasn’t fluent.

Then in her early twenties, she packed up, left her hometown, and moved to Little Grand Rapids to live with her grandma.

EISCHEN: It was very simple and … I like that simple way of life, like a non-materialistic kind of life.

WANSCHURA: And she decided to stay. She got an elementary school teaching job and settled into the community where most people spoke Anishinaabemowin, also called Ojibwe.

EISCHEN: I thank all my community members for, you know, just keeping the language alive and I love being around it because it’s a beautiful language.

Theresa Eischen and her gookom (grandmother). The name Theresa called her was Gaganaan. (credit: Theresa Eischen)

WANSCHURA: Over time, Theresa became fluent.

Fast forward about 25 years. One night last December, Theresa was sitting in her house in Little Grand Rapids. The news was on and a story caught her attention.

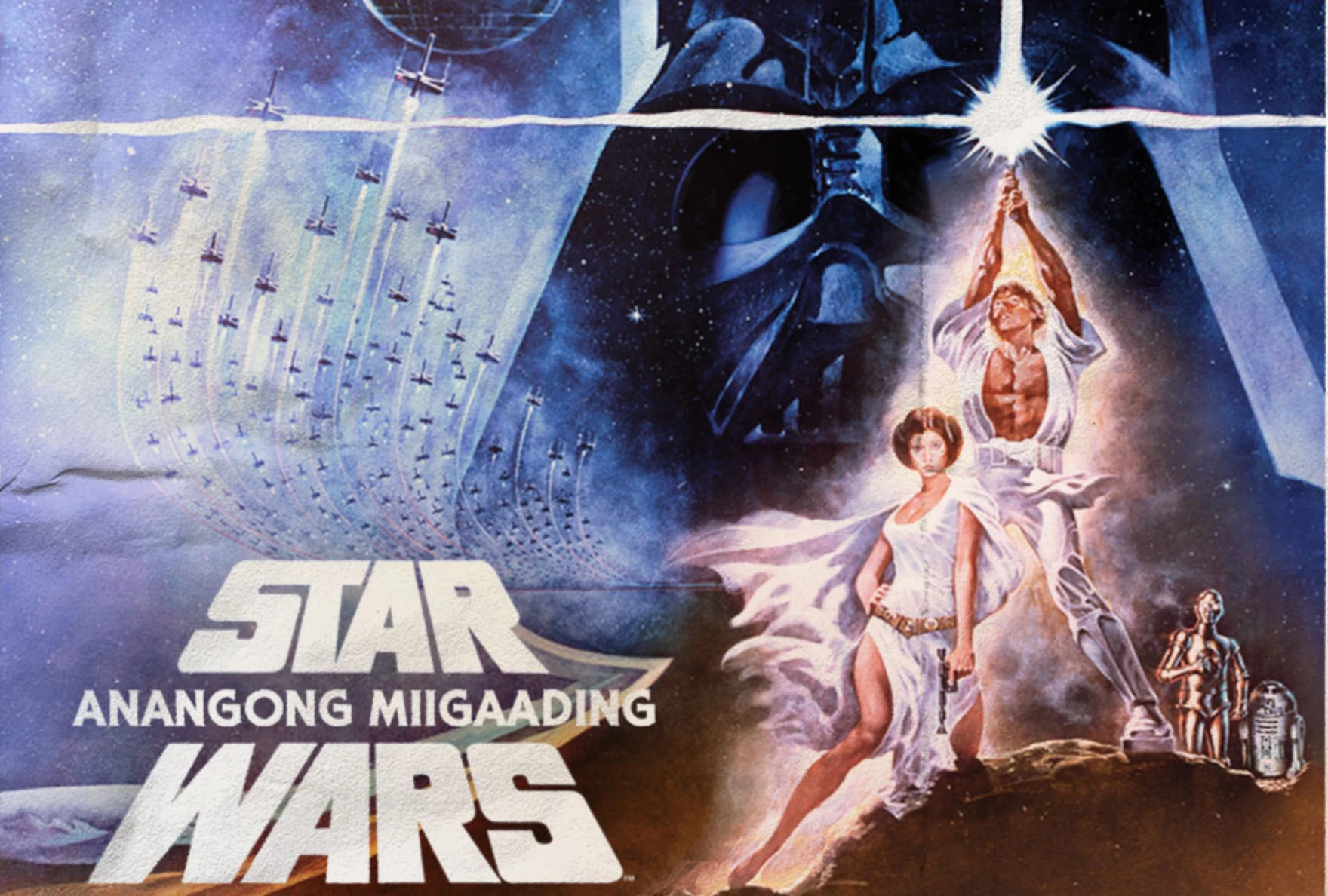

CTV NEWS: An open call for Ojibwe speakers. … Plans are in the works to translate and dub Star Wars – A New Hope into the Ojibwe language.

EISCHEN: I just got chills. I was like, ‘Wow, that’s really good! That’s so good for the Anishinaabe Nation.’

CTV NEWS: The translation is expected to happen next year. And there are plans for an eventual premier in Winnipeg.

WANSCHURA: Theresa loves Star Wars. She’s been a huge fan ever since she was a little girl. She saw A New Hope for the first time in a theater … as part of a double bill with The Empire Strikes Back.

Theresa had never imagined watching an Anishinaabemowin version. And by Disney no less.

Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope is one of the most popular films of all time. Since it was released in 1977, it’s been translated into over 50 languages, including Navajo. That was part of the inspiration for dubbing it into Anishinaabemowin. The project was trying to help revitalize the endangered language.

After that news story, Theresa didn’t really give it another thought. But a few days later, she got an email from her brother with the link to the film project.

EISCHEN: And he said, ‘You should audition.’

WANSCHURA: Theresa had zero voice acting experience. She taught elementary kids on the remote reservation. Really the only qualification she had was she could speak Anishinaabemowin.

She mulled it over for a few days, then decided what the heck. She started filling out the audition form.

EISCHEN: I wasn’t even sure if I was doing it right ’cause there was a lot of lingo in there about your experiences … as if I was like an everyday voice actor and I wasn’t.

WANSCHURA: But she heard back. They asked her which part she wanted to audition for.

EISCHEN: And of course, as we know, you know, there’s only basically, you know, Princess Leia is the, you know, the only female, really. … So, I said, ‘I want to audition for Princess Leia.’

WANSCHURA: So, the producers emailed Theresa an audition script – a single scene from the movie. It’s where Princess Leia meets Imperial Governor Tarkin … who’s in charge of building Darth Vader’s Death Star.

PRINCESS LEIA: ‘Governor Tarkin, I should have expected to find you holding Vader’s leash. I recognized your foul stench when I was brought on board.’

EISCHEN: And so I would practice like that and just practice in English. And then I would … emulate that voice in the Anishinaabe language. So when I speak it, so when I say it in the translation, I say,

‘Ogimaa Tarkin, giin nangwana omaa gidayaashkish. Aazha gigiiminaamin apii giibooziwigoowaan omaa, gi-maazhimaagoziwin.’

WANSCHURA: She recorded it, sent it in, and then waited. The more Theresa studied Princess Leia, the more the character resonated with her.

EISCHEN: She says what she wants when she wants it. She expects the best out of others, she’s resilient, you know, and she’s a leader.

PRINCESS LEIA: Listen, I don’t know who you are, or where you came from. But from now on, you do as I tell you, okay?

HAN SOLO: Look your worshipfulness, let’s get one thing straight. I take orders from just one person – me.

PRINCESS LEIA: Hmmm. It’s a wonder you’re still alive.

WANSCHURA: And then, she heard back again. This time the director wanted a live audition. The day of the audition arrived and Theresa logged onto Zoom. The director told her to go ahead and read her lines.

EISCHEN: And I’m looking at them and I’m just like, ‘Well, I’ve practiced so much, I don’t even need to read the lines. I just have to say the lines.’ And so I just went ahead and said them.

They said, ‘Wow, we like your voice. You have a very good voice.’ And I said, ‘Oh, thank you so much.’ You know, and that was the extent of it.

I didn’t ask any questions. I didn’t say anything about like, ‘When are you going to contact everybody?’ This is all going on in my head, but I didn’t want to ask, you know, it was just kind of like, ’If it’s going to happen, it’s going to happen.’

WANSCHURA: So there’s Theresa, with a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to be a part of Hollywood history. And she had no idea when casting decisions were gonna be made. Or even if she’d be notified if they went with someone else.

EISCHEN: I just was just enjoying the ride, kind of thing, not knowing maybe I’m just going to get dumped off somewhere at any given point.

WANSCHURA: Weeks went by and Theresa didn’t hear back. Until one night this March, she was in bed about to fall asleep. And she decided to look at her email one last time. There was a message from the film’s producer.

EISCHEN: I just remember reading the first line saying, ‘Congratulations. I’m happy to let you know that you’ve been casted as Princess Leia for the upcoming Star Wars in Ojibwe.’

Oh my goodness, I shot out of my bed like a cannon, and I was jumping up and down. And, you know, I hadn’t even read the whole email. And I was jumping up and down, yelling in the hallway, ‘I’m Princess Leia, I’m Princess Leia.’ I was just laughing so hard. I was just elated, you know. It was just a wonderful feeling.

WANSCHURA: But Theresa had to figure out a way to keep the news under wraps. She signed a confidentiality agreement, which meant she had to get creative about how she practiced so people wouldn’t hear.

EISCHEN: A lot of times I would do my lines in my truck.

If you were to say some of those lines as Princess Leia says them … with the sound coming out of her mouth and yelling and screaming and whatever, you would worry people in your community.

My cousins down the road would probably be concerned. ‘What’s going on over there?’ kind of thing.

PRINCESS LEIA: Will someone get this big walking carpet out of my way?

EISCHEN: Daga wiindamaw gichi-miishiz e-gibishkang?

‘Can somebody tell this big hairy thing that he’s in the way?’ is basically the translation.

Theresa Eischen records Princess Leia’s lines in a studio in Winnipeg, Manitoba. (credit: Lucasfilm, Ltd. / Disney)

WANSCHURA: Then this May, Theresa and the rest of the cast traveled to Winnipeg to record their lines in a studio. The key for these voice actors was to speak quickly. That’s because the Anishinaabemowin dub has to line up with the lip movements of the original English version.

EISCHEN: Our words are so lengthy that you really had to get it down.

WANSCHURA: At times the actors had to borrow a shorter English word to describe something. Like the word ‘droid.’

PAT NINGEWANCE: We’d have to say, ‘Gaa bimaadiziimagak biiwaabik.’ … A metal that can move around by itself, you know. … We can’t use that phrase over and over again. It wouldn’t fit the script.

WANSCHURA: That’s Pat Ningewance, a professor at the University of Manitoba. She was the lead translator for this Star Wars film. Other words like ‘lightsaber’ were easier to come up with.

NINGEWANCE: That wasn’t too bad. … Our translation is light and knife. A light knife, you know, a knife that shines, a shining knife.

That’s what it ended up, uh, being translated as ‘Waaskone mookomaan.’ It’s short and we used it over and over again. … It’s very descriptive, but it’s also a vivid translation.

WANSCHURA: On August 8th, 2024, the Anishinaabemowin version of Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope premiered at this huge concert hall in Winnipeg. Theresa Eischen was there with others from the cast and crew. There were photo ops, interviews – the whole red carpet experience. And hundreds of Anishinaabe people showed up to watch it.

Theresa Eischen takes a selfie at the premiere of the Anishinaabemowin version of Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope, in Winnipeg, Manitoba. (credit: Theresa Eischen)

EISCHEN: Everybody was just excited just to hear those lines. And some of those lines are very funny in the language. And just seeing our language written in the opening scene, that’s so exciting, you know, and you could hear it in the audience.

WANSCHURA: She saw people laughing. At other times, they got a little emotional. For Theresa, the whole experience was a dream come true. But there was someone who she wished could have been there.

EISCHEN: I always think about my grandma, a person who loved movies.

WANSCHURA: Sadly, Theresa’s grandma passed away about 12 years ago.

EISCHEN: I wish this had happened earlier. But I know even though she’s not here on this earth anymore … she’s watching, and my ancestors are going to be watching from the spirit world, you know. I truly believe that and they’re going to applaud that.

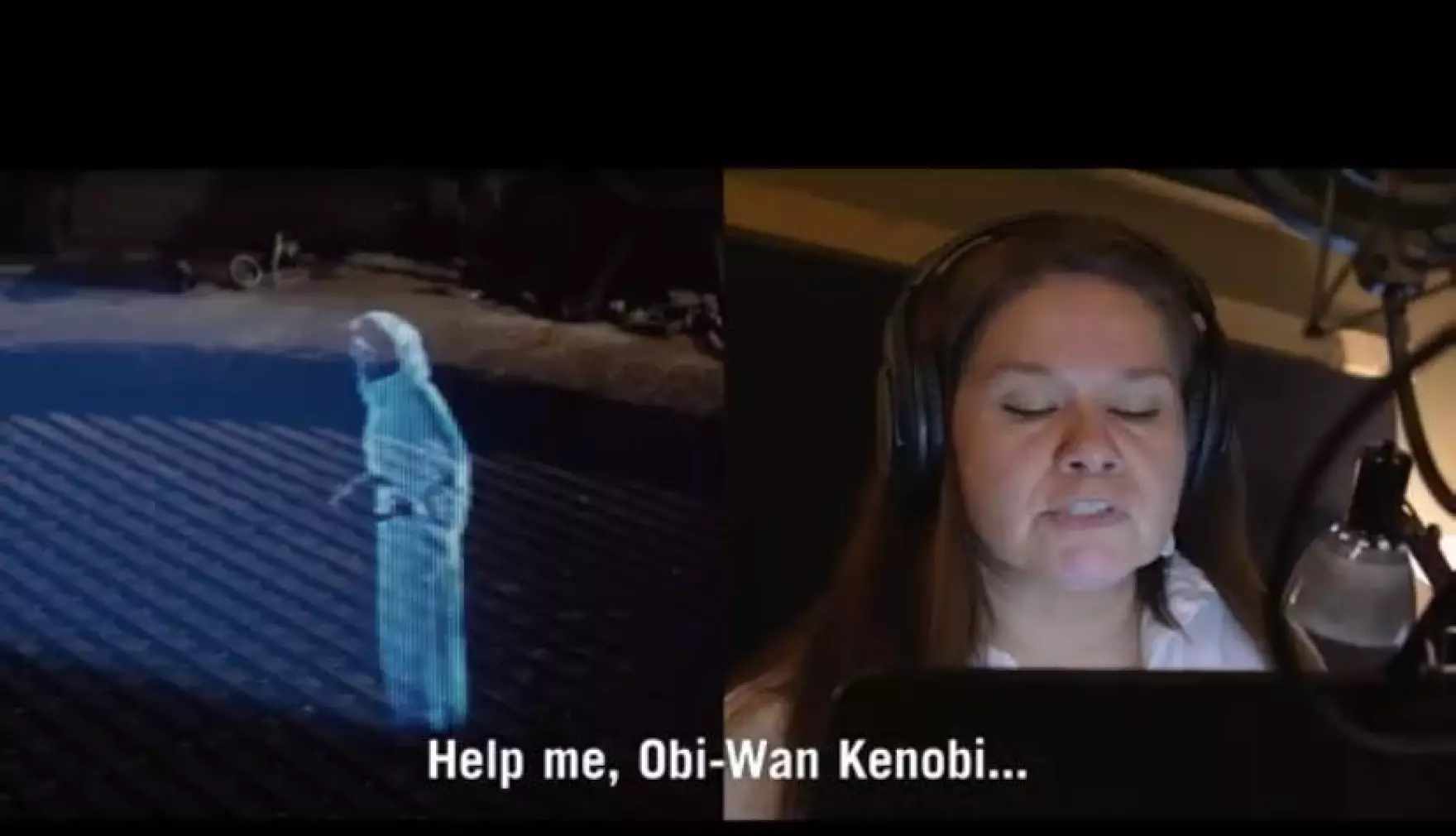

WANSCHURA: There’s this famous scene in A New Hope. It’s where the Jedi master Obi-Wan Kenobi gets a message from Princess Leia asking for help fighting against the Empire.

PRINCESS LEIA: This is our most desperate hour. Help me Obi-Wan Kenobi. You’re my only hope.

EISCHEN: Wiidookowishin Obi On Kenobi giin eta gibagosenimin.

WANSCHURA: That’s one of Theresa’s favorite lines. It’s a cry for help. But also a sign of hope. And that’s what this Anishinaabemowin film is about for her.

EISCHEN: I get emotional. And I know other Anishinaabe people can relate. And with this, I just want people to, I want, I guess, my story to give people hope. Not to give up in trying to learn their language. Because if I could do it, anybody can do it.

WANSCHURA: The film played in select theaters across the Great Lakes region, including in Ontario, Minnesota, and Wisconsin. It’ll also be available on Disney Plus later this month.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Points North: The Last to Leave

Points North: Labor of Mixed Emotions

Featured image: A poster for the Anishinaabemowin version of Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope. (credit: Lucasfilm, Ltd. / Disney)