Great Lakes Moment is a monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor John Hartig. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit PBS.

Traditional natural resource management used to focus on individual issues, like controlling pollution from industries and municipal wastewater treatment plants or managing a single species. As isolated pollution sources came under control and progress was achieved for individual species, the focus shifted to a more comprehensive ecosystem approach that accounted for all sources of pollution and targeted overall ecosystem health and resilience. Resilience is the capacity to respond to ecological disturbance by resisting damage and recovering.

An ecosystem approach was first championed in the late 1970s. At the time, it was a paradigm shift. No longer were humans considered separate from the environment, but part of an ecosystem. What humans did to their ecosystem they did to themselves. In contrast to historical environmental management that fostered autocratic decision-making, an ecosystem approach champions collaboration and empowering stakeholders.

Early on, an ecosystem approach was considered an aspirational goal of resource managers and a way of thinking. It has now evolved into a management framework and a way of acting.

Today, it is generally accepted to be a framework that integrates the management of natural landscapes, ecological processes, physical and biological components, and human activities to maintain or enhance ecosystem health and resilience. It acknowledges the interconnectedness of community, economy, and environment, involves all stakeholders, works to understand places and integrate processes, and pursues sustainability.

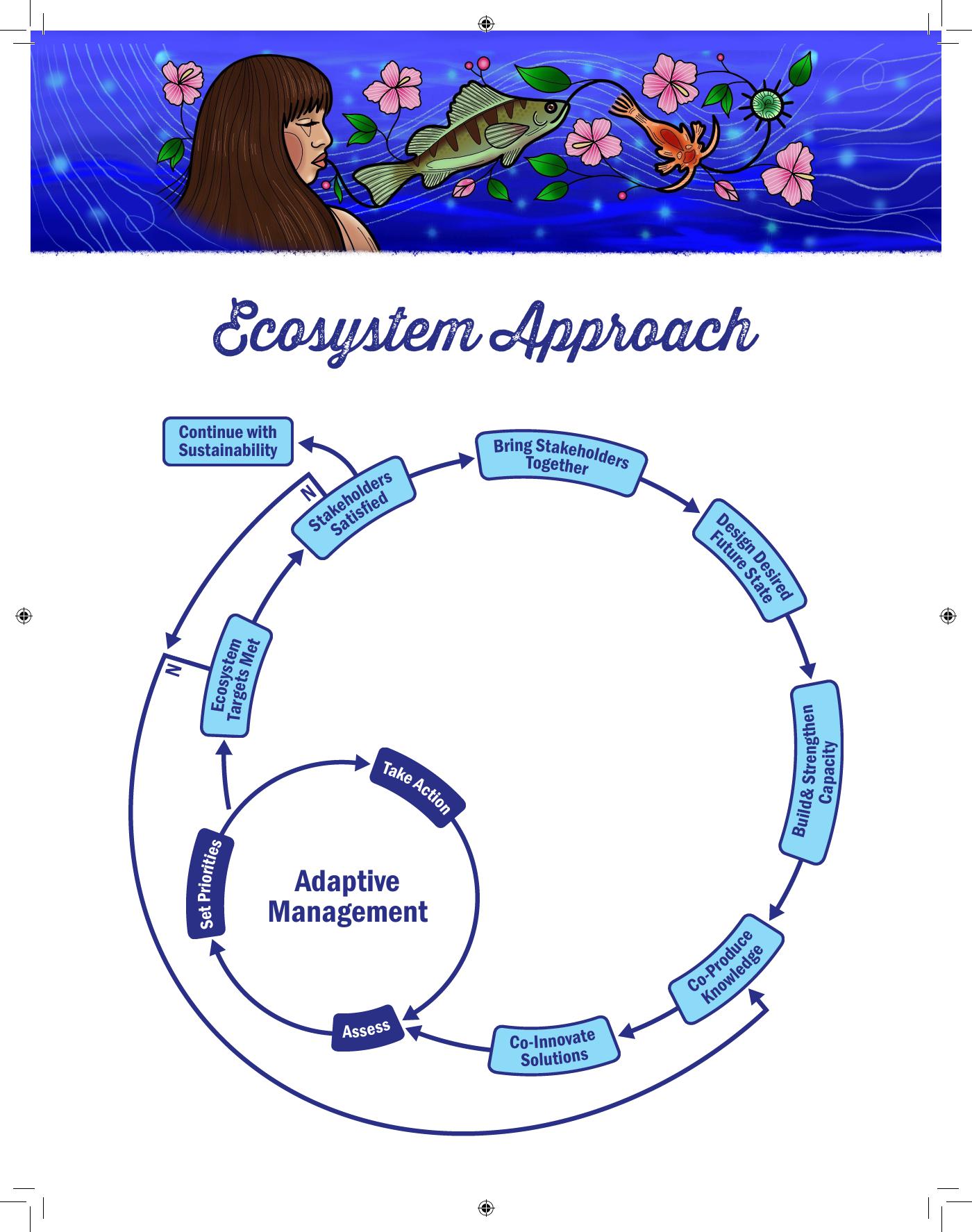

A recent study by the Health Headwaters Lab of the University of Windsor reviewed 12 ecosystem frameworks and recommended several action steps. These were designed to advance the use of an ecosystem approach.

Steps include bringing stakeholders and rights-holders together, building or strengthening capacity, co-producing knowledge, co-innovating solutions, and practicing adaptive management. The process of adaptive management involves assessing, setting priorities, and iteratively taking action for continuous improvement.

This study also identified 45 practical examples of ecosystem-based management where progress is being made toward long-term ecosystem health. These exemplars range from small to large scales and have a variety of local institutional arrangements designed to practice an ecosystem approach. One thing they all have in common is a boundary organization.

There are many boundaries and barriers to ecosystem-based management, including institutional, geographic, political, disciplinary, cultural, socio-economic, and more. An ecosystem approach requires spanning such boundaries and overcoming barriers in support of science-based decision-making. Boundary spanners are individuals or organizations that reach across borders and overcome barriers to build relationships to help restore and protect ecosystems.

Below are three key ecosystem approach exemplars, along with boundary spanners, examined in the study.

Buffalo River, Buffalo, New York

Substantial water pollution of the Buffalo River resulted in it being designated as a Great Lakes pollution hotspot or Area of Concern in 1985. Initially, the process was led by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. After a slowdown in the cleanup progress, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency selected the Buffalo Niagara Waterkeeper as the first nonprofit organization in the Great Lakes to re-energize the restoration process in an Area of Concern, coordinate implementation, and serve as a boundary organization.

Over time, this Waterkeeper and many partners brought in over $100 million to restore the river using a locally designed ecosystem approach. Cleaning up the Buffalo River spurred improving public access to the river that contributed to waterfront economic revitalization, including more than $428 million of waterfront development between 2012 and 2018.

Commitment to an ecosystem approach gave the Buffalo Niagara Waterkeeper freedom to experiment with multidisciplinary teams and approaches to problem-solving. Key strengths included developing a bold vision and sharing it broadly, co-production of knowledge, co-innovation of solutions, well-recognized community benefits, and grassroots advocacy.

Saugeen Ojibway Nation, Ontario

The Saugeen Ojibway Nation lives in the vicinity of the Saugeen (Bruce) Peninsula which divides Georgian Bay of Lake Huron from the lake’s main basin. This First Nation and the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry collaboratively manage the commercial fishery within the Saugeen Ojibway Nation’s traditional territorial waters.

In concern for declining fish stocks in Georgian Bay, the Saugeen Ojibway Nation began working more closely with the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry and the Great Lakes Fishery Commission on integrated fisheries research and science-based management. This collaboration is guided by “The Two-Eyed Seeing” approach. This approach includes learning to see from one eye with the strengths of Indigenous knowledge and ways of knowing, and from the other eye with the strengths of mainstream knowledge and ways of knowing. The goal is to use both of these eyes together, for the benefit of all.

Saugeen Ojibway Nation serves as a boundary organization, helping translate knowledge into better management of the commercial fishery, consistent with the Anishinaabe concept of Wesindamay, or “walking together.” Key strengths include stakeholder engagement, mutual respect and understanding, shared decision-making, co-production of knowledge, co-innovation of solutions, and adaptive management.

Severn Sound, Ontario

Severn Sound is a complex of bays and inlets in the southeastern Georgian Bay of Lake Huron. It too was designated as a Great Lakes Area of Concern in 1985.

The cleanup process started as a federal-provincial government initiative. To foster the use of an ecosystem approach, it had to evolve into a partnership called the Severn Sound Environmental Association – a boundary organization. It included federal, provincial, and municipal governments, as well as other organizations. This association was instrumental in fostering use of an ecosystem approach, ensuring local ownership and acceptance, sustaining long-term restoration efforts, and facilitating the transition to sustainability.

The combination of strong public involvement and a comprehensive, cost-effective plan resulted in the implementation of remedial and preventive measures and the successful removal of Severn Sound from the list of Great Lakes Areas of Concern in 2003.

Study Recommendations

Major recommendations from this study include:

- Priority should be placed on the development of boundary spanners to serve as facilitators, knowledge brokers, and champions of strengthening science-policy-management linkages

- Establish an ecosystem approach community of practice that includes resource managers, researchers, educators, and practitioners

- Prioritize breaking down the “silo mentality” – an unwillingness to share information or knowledge between or across different departments or organizations – and improve communication to foster co-production of knowledge and co-innovation of solutions

- Resource managers should prioritize building trustful relationships and capacity-strengthening efforts that enable the incorporation of Traditional Ecological Knowledge into every step of ecosystem-based management

- Ecosystem approach watershed education should be included in the curriculum of K-12 students and educator training for all Great Lakes states and provinces

For more information about this study, visit:

An Ecosystem Approach: Strengthening the Interface of Science, Policy, Practice, and Management

John Hartig is a board member at the Detroit Riverfront Conservancy. He serves as a Visiting Scholar at the University of Windsor’s Great Lakes Institute for Environmental Research and has written numerous books and publications on the environment and the Great Lakes. Hartig also helped create the Detroit River International Wildlife Refuge, where he worked for 14 years as the refuge manager.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Great Lakes Moment: Detroit River’s important role in lake whitefish

Great Lakes Moment: Gordie Howe International Bridge becomes part of binational trail system

Featured image: An ecosystem approach to natural resource management. (Photo Credit: Nik Charette/University of Windsor’s Healthy Headwaters Lab)