While gathering in Montreal recently, perhaps the Great Lakes region’s mayors took a page from urban planner Daniel Burnham’s playbook which said, “make no little plans.” From Burhham’s legendary Plan of Chicago.

At the mayors’ annual conference, the focus was on nothing less than an “economic transformation” in the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence region with the theme, “Tapping into Water for Sustainable Prosperity.”

The 10-year plan will launch in 2025 and calls for the region to “become a globally renowned economic corridor.” The region’s water, innovation and sustainability are at the core of the plan.

To take a closer look at the ambitious initiative, Great Lakes Now recently spoke with Rob Sisson, a former U.S. commissioner on the International Joint Commission (IJC), the Canada-United States agency that advises the countries on transboundary water issues. Sisson previously served as president of ConservAmerica and was mayor of Sturgis, MI.

Sisson commented on the plan and added words of caution for the mayors. He was circumspect about a reliance on innovation, and explained the “myth of abundance” in regard to water in the region.

The interview was recorded, transcribed and edited for length and clarity.

More here on the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Cities Initiative economic transformation plan.

Great Lakes Now: The Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River mayors organization recently announced an initiative to transform the Great Lakes St. Lawrence basin into a blue-green economic development corridor. One where “the basin’s freshwater catalyzes increased economic opportunities for innovative businesses.” What’s your high-level take? Is it feasible given the breadth of the region over eight states, two federal governments and multiples of municipalities, differing regulations and more?

Rob Sisson: It’s definitely feasible. As you know the Great Lakes region itself would be the world’s third largest economy if a government by itself. But it’s not so much “transforming” the economy but perhaps transitioning from the Rust Belt type of economy to modern tech.

I was shocked once going to New Mexico and seeing an Intel chip manufacturing facility. Chip manufacturing takes a lot of water. I have no idea why they would locate in the desert.

The Great Lakes mayors really need to be prepared beyond just being ready to accept the next opportunity that comes for the long term. Climate refugees and manufacturing will rebound back to the Great Lakes region and the cities need to have capacity and the infrastructure in place to deal with it.

GLN: The initiative said the mayors want to tap into the region’s water for “sustainable prosperity.” There is no mention at this point of conserving water. Sustainable can mean different things depending on the user’s interpretation. How do you see water as an economic development tool as the mayors have presented it?

RS: Water for the next 25 years will probably be one of the primary economic development tools available to states, provinces and municipalities. That’s because so many manufacturing processes require water. As someone who grew up in Michigan, I watched in the 1970’s as manufacturing abandoned the Great Lakes region for the south where there was cheaper labor and lower utility costs.

I see a return to the Great Lakes region because of the water. The mayor’s plan is a good one but they need to make sure they’re prepared. As many in your audience will know, use of Great Lakes water means putting it back into the system after treatment and it stays in the basin. My concern is the infrastructure piece. That needs to be in place before we go full tilt recruiting people and business back to the region.

GLN: Do you think the mayors realize that or do they see it as someone else’s problem?

RS: I think they do. Because there’s become a big reliance on state and federal funding for that type of infrastructure. Rather than mayors, it’s more for the populace that needs to be aware of it.

When I was mayor of Sturgis, MI we almost annually raised the rates for wastewater service. That’s because we were determined to invest to make sure our system was state of the art and could handle what came its way related to growth. In Sturgis, our waste and stormwater all go into a system that feeds into the Great Lakes. We were aware of that as municipal leaders but I’m not sure the people who pay taxes for services and who adore the Great Lakes are aware.

GLN: Regarding water as an economic development tool, the city of Chicago in 2023 agreed to sell Lake Michigan water to Joliet, IL which is well outside the Great Lakes basin. Such a sale would normally require a rigorous examination of the need then approval by the Great Lakes governors based on the Great Lakes Compact.

However Chicago’s sale is allowed based on a Supreme Court decree and Chicago has hinted that it may seek additional water sale opportunities to generate revenue for the city. Is that a good message?

RS: I don’t think that’s a good message although it’s a fair message as they do have the Supreme Court decision that governs their withdrawals from Lake Michigan.

The thing I’d be worried about in Chicago and the metropolitan area is what if we need that water back in 10, 15 or 20 years. Will they cut off the municipalities that have come to rely on us providing that water? I worry that we will oversell the commodity or resource and then get pinched down the road.

GLN: Innovation is having a moment and at the recent Chicago Water Week conference it was in the spotlight along with promotion of the Blue Economy. Can we innovate our way to sustainable water management? Is there a risk of over-reliance on technology at the expense of water conservation?

RS: Innovation is a nice $100 word. But we can’t define it until something is innovated in the future. We know we need to conserve and use less water and better care for it. And we need to treat it and put it back into the basin in a form that’s drinkable, swimmable and fishable. It sounds simple and I’m sure there are innovations coming that can help us with that, but we know how to do it right now.

I don’t think banking on something down the road to make us feel good about shipping water out of the basin or using water in a non-sustainable way today makes sense.

GLN: As you have traveled the length of the U.S. and Canada border for water issues, how do people see water? To be conserved or as a tool for economic development, or maybe they don’t think much about it?

RS: It’s not just the U.S. and Canada, we’re also talking about Indigenous nations along the border and in the Great Lakes region and they have to be taken into account too.

The people with whom I interacted as an IJC commissioner care deeply about water. Whether it is the source of sustenance, a key agricultural input for irrigation, a place for recreation or an economic development tool. These people work with water daily and understand today’s abundance may be tomorrow’s drought.

Unfortunately, there are people who don’t think much about water or take it for granted. Their only interaction is to turn a faucet on and water pours forth, with no thought about natural and manmade systems that make that possible. Water impacts the daily lives of every one of us and we need to do a better job of educating the folks who aren’t out in boats fishing, wrenching irrigation valves, or carrying a five-gallon jug of water home from a community spigot. One-quarter of the world’s population still doesn’t have access to clean drinking water!

Thankfully, Indigenous voices are increasingly being heard along the entire transboundary. Their ancient wisdom and respect for nature is beginning to affect western science and minds in how we look at water. An Anishinaabe woman once pointed to my glass of water and said, ‘Molecules of water in your glass may have been in your mother’s womb, protecting you before you were born. Every drop is sacred.’

GLN: Canada’s Maude Barlow, a former adviser on water issues to the United Nations, talks about the “myth of abundance” that exists in the Great Lakes region. That our water supply is infinite but we only recognize the myth of abundance after experiencing it. Does Barlow have a point? And I’d cite the Colorado River’s situation where its limitations didn’t receive proper attention until it was nearing a crisis.

RS: Barlow is absolutely correct. Circling back to the first question, it’s incumbent on leaders in the Great Lakes region to reach out to every citizen to educate them about water and the Great Lakes and that it isn’t an infinite resource.

In 2012 water levels were near all-time lows and the IJC had people petitioning to build a dam in the St. Clair River to hold water back into the Great Lakes. Then years later water levels were at an all-time high and people wanted us to pipe it to the southwest’s arid states. All it takes is one short period of drought to put fear in people that water may not be high enough to draw it into our municipal drinking water systems and for toilets and firefighting.

I live now in Bozeman, MT and we know that there’s not enough water here, yet new development is rubber-stamped by officials thinking that we’re going to innovate our way out of this shortage.

Last year I represented the IJC at the United Nations water conference. I sat in the General Assembly and listened to heads of state from around the world bemoaning the fact that their country doesn’t have water for sanitation and health. They talked about the collaboration they need to do regionally and across continents to ensure that their people can survive and live.

In the Great Lakes region I agree with Barlow, the average citizen needs a wakeup call. That water is a precious resource not only for the region but globally. It may be the most important resource in the world.

GLN: Given your years on the frontlines of water stewardship in the U.S. Canada, and with Indigenous Nations, what is the status related to water of those relationships between the entities?

RS: I can’t speak for Indigenous people but just before I left the IJC in March the two governments gave the IJC the first new reference in over 40 years and it was in partnership with the Ktunaxa Nation. That was innovative and precedent setting and I think going forward we will see the two countries in their work with the IJC include Indigenous Nations as equal partners in references in the work of the IJC.

GLN: Final thoughts? What’s important to know for the average U.S. and Canadian concerned citizen about Great Lakes stewardship and the government entities charged with their conservation and protection?

RS: There is a thread through this entire conversation that people need to make the connection between the Great Lakes region being the third largest economy in the world. How powerful that is and what it means to their work. income and future prospects for their children and grandchildren. And how quickly that can turn if we don’t take care of the water.

It’s important that people take a vested interest in the lakes and make sure our leaders make decisions for the sustainability of the lakes and the regional economy.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Wisconsin’s Jane Elder chronicles personal and professional Great Lake’s journey in new book

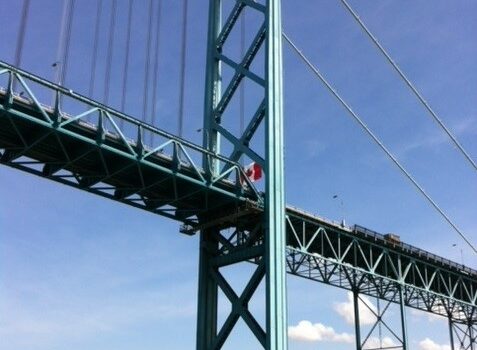

Featured image: Detroit River approaching the Ambassador Bridge. (Photo Credit: Gary Wilson)