This is part one of a two-part series on heat islands around the Great Lakes. Part one is on the human health cost. Part two is on the science behind urban heat islands, solutions to the complex problem, and the role the Great Lakes play.

In Cleveland, Ohio, it’s best to leave the city proper and head to the suburbs for a big outdoor celebration. This is only because parks within the city don’t have nearly enough shelters or a system that allows families to rent these limited spaces for the day — which can cause quite a rift among neighboring party throwers, according to Aletha Acree, 51, who has lived in Cleveland all her life.

On Sunday, June 2, Acree and her extended family had a big summer barbeque but had to head out to Stafford Park in the suburb of Maple Heights. There was a band, a DJ, and tons of games — a lot was invested in this party for them not to have a guaranteed shelter, as shade is one of the most important considerations at Acree’s summer family gatherings.

“I definitely wear a sun visor or a hat, I put on sunscreen, I put on the loosest airy clothes — I have something like linen, and I try to stay under the shelter for the most part,” said Acree. “I either go right before the sun comes up in the afternoon, or I go after it’s starting to go down, and my family generally tailors everything to that — for me.”

When Acree was 16 years old she was diagnosed with Lupus, a chronic autoimmune disease that affects many parts of the body like skin, joints, blood cells, brain, heart, kidneys, and lungs. For Acree, too much exposure to the sun was causing a rash around her nose, commonly known as a “butterfly rash,” and such extreme migraines that she was in the emergency room at least once a month during the sunny, warmer seasons.

This went on for years, because Acree said she’s an active person who was always out on weekends doing different things, like riding horses. Until 13 years ago, when she joined a support group at the Lupus Foundation, where she now works as a Community Outreach Coordinator.

“I’m African American, and I was one of those people who was like, ‘we don’t need sunscreen,’” laughed Acree. “It wasn’t until I came to Lupus Foundation that I found out that, ‘hey the sun irritates – the sun causes these things.’ Those weren’t even things that I had discussed with my doctor. They were just happy to have me moving around and being active. We didn’t even discuss the sun, and I didn’t correlate that the sun was causing the fatigue or worsening symptoms.”

Despite being on the Great Lakes, the cities of Cleveland, Chicago, Detroit, Milwaukee, Windsor, and Toronto have all been labeled urban heat islands. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), heat islands are primarily urban areas with a lot of buildings and infrastructure that absorb and re-emit heat from the sun, creating a higher temperature than outlying areas where there is more natural landscape, like forests or water.

According to Climate Central, metropolitan areas that are known as urban heat islands are hotter than their outlying neighborhoods. Urban areas can experience peak temperatures that are 15°F to 20°F hotter than nearby neighborhoods with more trees and less pavement. (Illustration by Matt LeBarre)

One of the largest problems currently has to do with cultural orientation to heat; because heat is seen as a relatively new issue in the Great Lakes region, the tracking of heat-related health events in this part of the United States and Canada is lacking.

According to a recent Axios-Ipsos poll, two-thirds of Americans are worried about the health impacts of climate change. Data from the United States Census Bureau in 2023 suggests that about one-fourth of Americans are vulnerable to extreme heat exposure; either socially (meaning they cannot afford their energy bills) or they have health concerns (meaning they have low resilience to extreme heat). The 2022 Canadian Survey on Disability showed that 8 million Canadians are living with health limitations, some of which could make them vulnerable to heat.

“Without a doubt, I think every emergency department across the country during the heat spells, especially when the heat gets above 88 to 90 degrees, experiences an influx of people, especially in the heat islands,” said Dr. Patrick McHugh, an emergency room physician with Cleveland Clinic at Akron General.

McHugh also has a fellowship in wilderness and environmental medicine and said that dehydration is the biggest factor when it comes to the dangers of heat. It’s not just about staying cool and drinking enough water, but making sure people are replenishing with enough electrolytes and minerals when they’re sweating a lot.

And the list of ways McHugh says a body could be negatively impacted by heat is almost overwhelming. Some of this includes:

- Various medications, such as beta blockers, prevent the heart from beating fast, and for that reason they are not able to dissipate the heat that their body is feeling. Also, psychiatric medications like antipsychotics or ADHD stimulants can mess with hydration.

- Cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy are vulnerable to dehydration.

- Autoimmune conditions such as Lupus or Multiple Sclerosis can make people more prone to dangerous symptom flare-ups during extreme temperatures.

- Heat also triggers issues breathing for anyone with asthma or COPD.

- Young children, pregnant and elderly people are more susceptible to dehydration and heat intolerance.

- More than half of the millions of people struggling with long COVID or diabetes who also have dysautonomia issues, meaning the autonomic nervous system — which helps to regulate automatic functions of the body, like the body’s response to heat — have thermoregulation issues.

- Anyone with cardiovascular issues is more at risk for having another event like a heart attack or stroke.

This means water shutoffs and rising energy costs across the region also play a role in public health when it comes to managing heat, according to Becky Rose, a geographer at University of Wisconsin-Madison. Rose recently studied what she refers to as “heat mitigation” versus “heat management” in northern cities in the United States, where heat is a more recent concern.

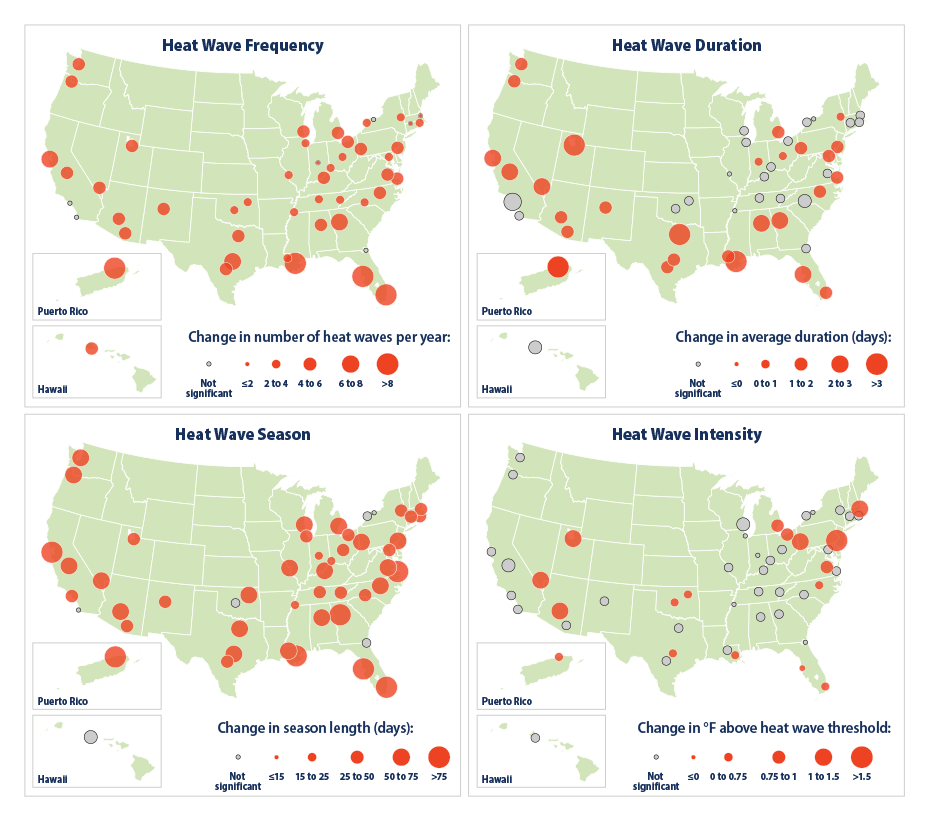

Data from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency about heat wave characteristics in 50 Large U.S. Cities, from 1961–2021.

Heat mitigation is what the city is doing to cool down long-term, like reducing automobile traffic with more bike lanes and prioritizing public transit, green roofs or painting roofs a lighter color to reflect sunlight, or planting trees and creating more shaded greenspace. Heat management is about what a city is doing in the short-term to ensure residents have access to air conditioning, clean drinking water, hospital preparedness, city-wide warning systems, and community structures so people are checking on vulnerable neighbors who are living alone — anything that can be done in the moment.

What Rose discovered was that many of these cities scored very well in terms of long-term heat mitigation. Especially Chicago, she noted, likely after experiencing what is now known as the “1995 Chicago Heatwave” where within five days, over 700 people died of heat related deaths. Milwaukee was also affected during this same heatwave, having lost nearly 100 residents during that same time. However, according to Rose, all the northern cities she studied did not score well in terms of heat management.

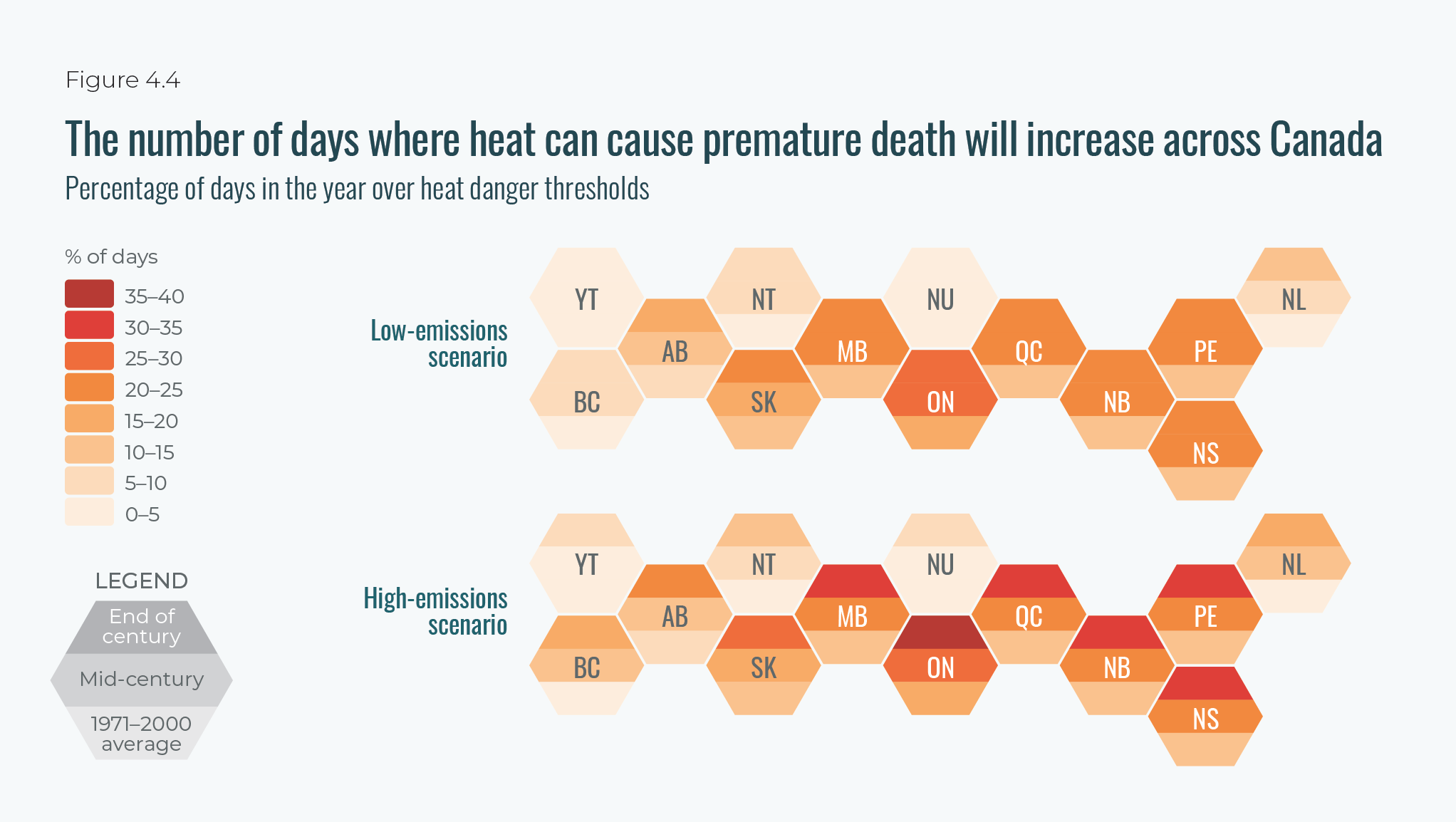

This graph shows the potential number of days when heat could cause premature death for Canadians, based on whether or not global emissions are reduced. (Data from the Canadian Climate Institute, 2023)

This makes sense after speaking with Mobile Care Chicago — a traveling health organization also known as the “Asthma and Allergy Van” — as well as the Night Ministry, also from Chicago. Both said there were obvious inequalities in terms of where trees have been planted, whose roofs are being painted lighter colors and communication around where cooling centers are and what their hours are.

Redlining and segregation, in many areas still defines where different racial groups live in U.S. cities, according to bioclimatologist Scott Sheridan, who has extensively studied the relationship between climate and people. He said, a lot of the more “preferable” neighborhoods tended to have more vegetation and less dense housing, which all reduce the urban heat island. Looking at areas that were more marginalized in the redlined areas, they always had a lot less vegetation, denser housing, and a lot more concrete.

“I was part of looking at resilience within the city of Cleveland, where we looked at the mortality rates during heat events for different subpopulations,” said Sheridan. “We saw that Black people were more vulnerable than white people, which tends to be shown in a lot of studies throughout the U.S., that racial minorities are more heavily affected by heat events than white people. And a lot of that is not due to physical differences but comes down to issues of socioeconomics. And so you actually see environmental justice issues where you tend to have minority populations that are living in areas that have greater heat islands, as a result of the legacy of what happened many years ago.”

Sheridan went on to describe why definitions of extreme heat differ from city to city. This is something he had to consider while helping develop warning systems for cities like Toronto and Chicago. It all depends on what a person is used to. Once a temperature jumps beyond what someone is used to, especially during that first heat wave of the year — that is when things are most dangerous, because there’s been no transitional period to slowly acclimate the body.

These are graphics from U.S. EPA on how to stay safe and who is vulnerable during extreme heat events.

“This tends to affect a lot of outdoor workers,” said Sheridan, expanding on how seasonal jumps in temperature are dangerous: “If you’re acclimatized to a certain set of weather conditions, and then you have something anomalous to what you’re used to over the last several months, it takes you a while for your behavior to adapt to that. You have your summer routines for how you go about your day and your winter routines for how you go about your day. And the transition that we make — you don’t really think about — but there’s obviously a lot of behavioral decisions involved.”

Placing the short-term burden on residents

Matt Siemer is very aware of air conditioning. It’s one of the first things he notices about a place, as a person who has been living with severe asthma since childhood. Not only because air conditioning cools an environment, making it easier to breathe, but also because it contains a filter that helps reduce certain irritants that might trigger an attack.

“Preparation becomes really important, like being ready if something were to go wrong, and in many cases, we’re putting this burden on 6 and 8 year olds, to be moving around their environment and in a state of readiness,” said Siemer, who works as the Executive Director of Mobile Care Chicago.

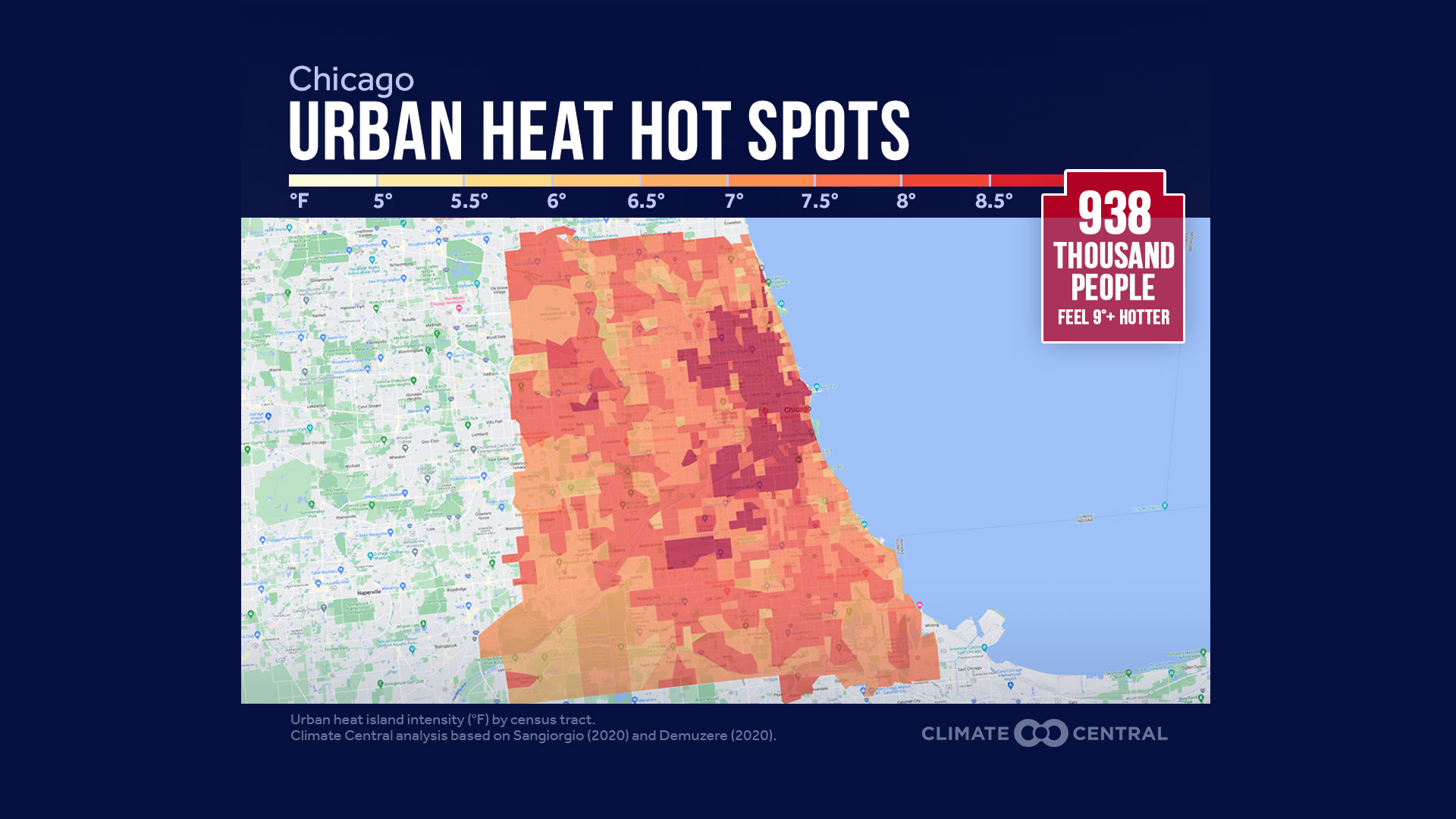

In 2023, a Climate Central analysis found that 938,000 Chicago residents are experiencing the urban heat island effect.

He said many of their clients are children located in the heat island neighborhoods of Chicago, like Humbolt Park, Pilsen and Little Village, and Gage Park. They work with 55 different school sites, have a 24-hour hotline, and in years past have donated air conditioning units to low-income families.

Before Simer leaves his house in the summer to do something physical, like hiking, he makes sure he has taken his antihistamines, grabs his inhaler and has enough water to drink. This kind of preparedness is something Stephan Koruba, medical director and family nurse practitioner, and Summer Kee, a psychiatric nurse practitioner, advocate for their patients at The Night Ministry. Many of their patients are dealing with housing insecurity or struggling with substance use.

Koruba recalls one of his former patients, who spent many years on the street. This patient had a history of heart failure that was likely from his history of IV drug use. Devastatingly, his patient ventured to the west side of Chicago on a very hot day and ended up overdosing in a field. The west side of Chicago is known for being the most extreme part of the city’s heat island, as it’s farthest from Lake Michigan. Koruba said it took days to find him in the tall grass.

“I really do think that the heat contributed in two ways,” said Koruba. “For one, I know his activity tolerance was less. But also, he didn’t have this partner that … normally would travel with him, because they didn’t want to go out in the heat. What we talk about for harm reduction is to [stay] with a partner who can keep an eye on you.”

People in the Great Lakes region might be used to living comfortably without air conditioning, but, the climate is changing much faster than the pace of most people, or even city infrastructure, is capable of adapting. Most of the experts Great Lakes Now spoke with said all these cities are putting a lot of the responsibility of heat management, things that could be done in the short-term to prevent serious health events, onto individual residents who are suffering at grave costs in the long-term.

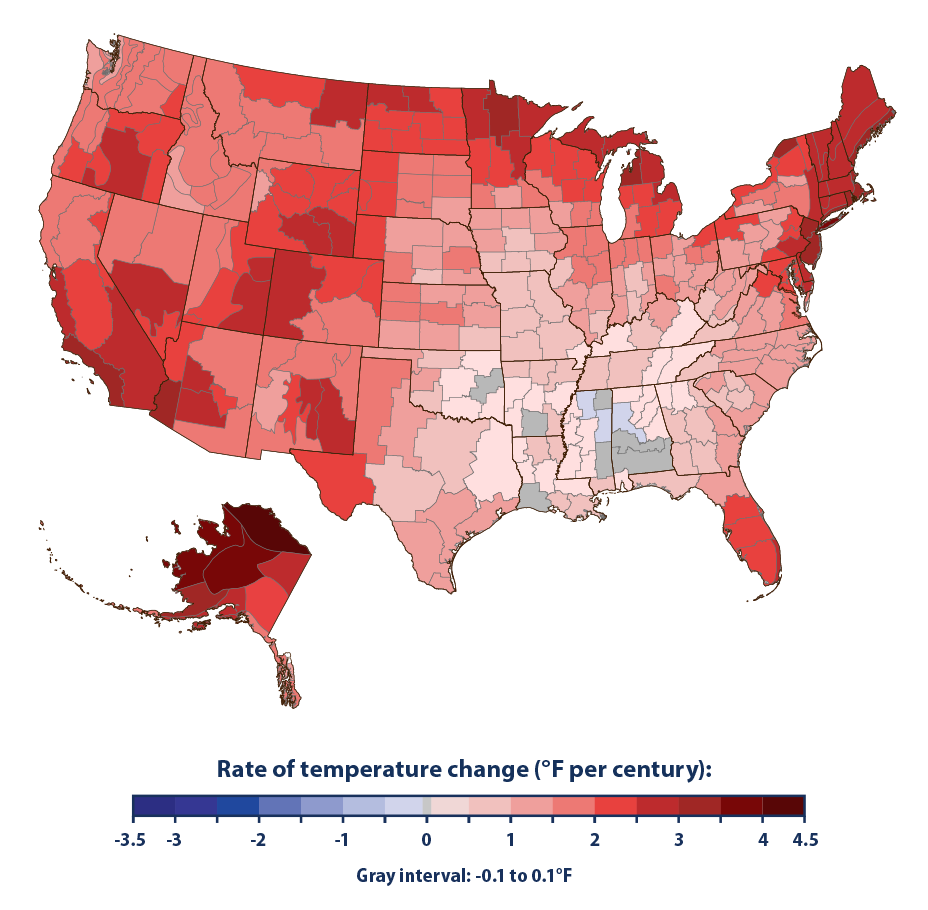

Rate of Temperature Change in the United States from 1901–2021, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Other cities closer to the equator might be more used to living with extreme heat, and might have more plans in place to manage that. But with April 2024 being the world’s hottest on record, inspiring United Nations Secretary General António Guterres to demand that fossil fuel companies pay a “windfall” profit tax, after the planet also endured 12 straight months of record-breaking heat — it’s safe to say no matter where someone lives, it is the hottest it’s ever been.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Looking for a US ‘climate haven’ away from heat and disaster risks? Good luck finding one

As Great Lakes warm, collaboration and Indigenous self-determination are keys to adapting

Featured image: Young children tend to be more susceptible to extreme heat. Having access to water and shade is vital. (Illustration by Matt LeBarre)