I Speak for the Fish is a monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor Kathy Johnson, coming out the third Monday of each month. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit Public Television. Check out her previous columns.

I Speak for the Fish is a monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor Kathy Johnson, coming out the third Monday of each month. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit Public Television. Check out her previous columns.

Spend enough time on a Great Lakes fishing pier or in a bait and tackle store, and you’ll likely hear someone ask if the lakes have flipped.

As a diver, I’ve spent a lot of time in the vicinity of sport fishers and have overheard more than one asking if the lakes flipped yet. Their question usually garnered a quick and decisive yes or no.

Understanding what it means for the Great Lakes to “flip” is invaluable for anyone interested in finding fish.

It’s also useful to know how water temperatures affect fish when discussing climate warming trends. For instance, a lack of ice cover in the Great Lakes is not only bad for lake levels, it also negatively impacts the lakes’ inhabitants.

Native Great Lakes fish are categorized as coldwater species, but only some tolerate the icy waters of winter.

All native Great Lakes fish are categorized as coldwater species, but some like yellow perch prefer warm water while others like lake trout thrive in icy cold waters.

Most of the year, the cold water lovers can be found deep in the lakes and the warmer-water fish are up in the shallows.

In the winter, and during some weather events, the lake temperatures and corresponding groups change places, or flip.

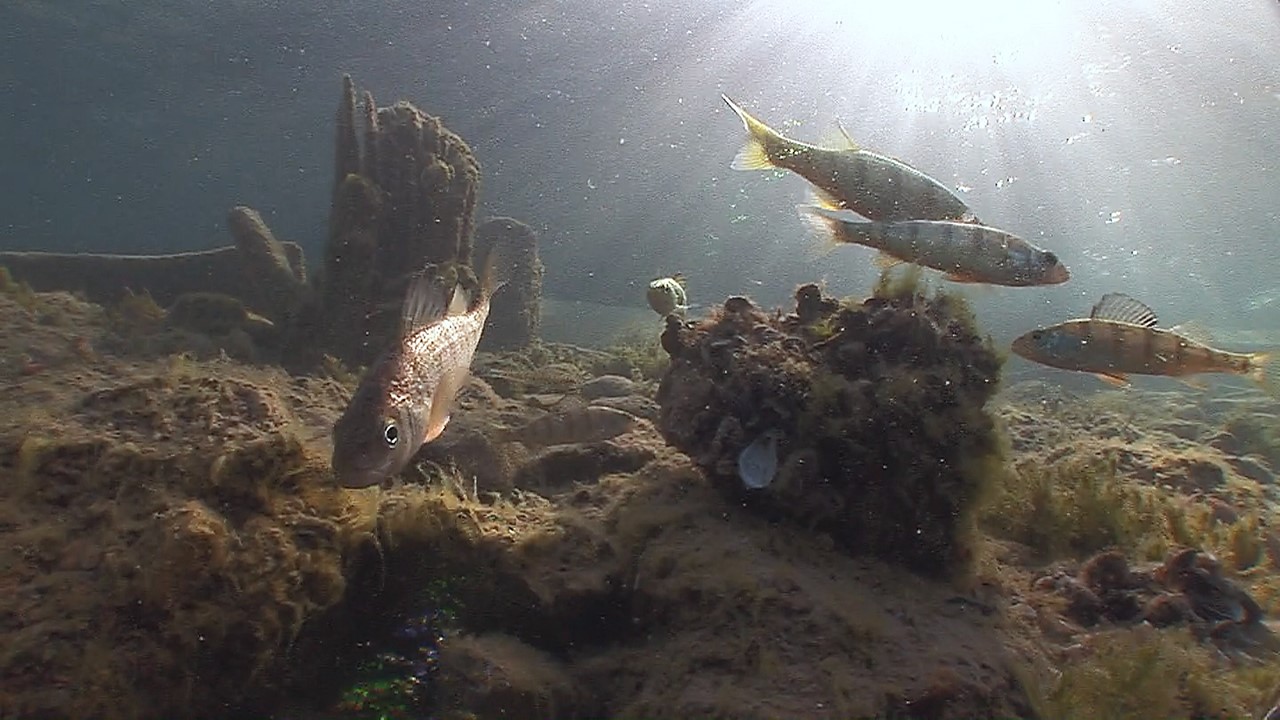

Perch in the shallows. (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

Aquatic seasons

My quest to learn more about why the Great Lakes flip and how this impacts fish in the winter led to three engaging conversations.

First, I spoke with Judy Ogden, a Great Lakes Fishery Commission member and seasoned sport captain and then Mike Thomas, a retired Michigan Department of Natural Resources research biologist. Lastly, Eric Anderson, a hydrodynamicist at National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

All three were familiar with the lake flipping concept but the scientists referred to the seasonal top-to-bottom change by a slightly different term. They call it the turnover.

Seasonal temperature changes are the primary driving force behind the turnover or flip.

Ice is the lightest form of water which is why even in an ice-cold beverage ice cubes still float.

Paradoxically, warm water is also lighter than cold water which is why the bottom of lakes and ponds are typically colder.

Water is densest or heaviest at 39 F. At that temperature, water sinks which is why the deepest parts of the lakes are perpetually 39 degrees.

Historically, cold winter air causes water temperatures to drop until eventually the surface ices over. With the surface at 32 degrees there is now only a 7 degree spread between the shallow water temperature and the bottom temp. Not a big difference but every degree counts.

In the spring, as the days grow longer and the sunlight strengthens, the surface begins to heat up. As the water warms, it will reach a point where everything from the surface to the bottom is 39 degrees. That is the spring turnover point.

As summer progresses the shallow water continues to get warmer and warmer. However, because midwestern summers are not historically long enough or hot enough to warm the lakes all the way through, the bottom remains 39 degrees.

By the end of August, there can be more than a 30 degree difference between the shallows and the depths. This large temperature difference creates distinct layers called thermoclines.

Fall ends the surface warming cycle and once again the shallow waters begin to cool. As the temperatures continue to drop the water will reach the second 39 degree turnover point of the year, and once again the coldest and warmest zones will flip.

Fishing. (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

Snow fish

Each fish species in the Great Lakes responds differently to the seasonal changes.

There are commonalities. Most spawn in the spring and summer. And come fall, most relocate somewhere to overwinter.

Where they go depends in part on whether they are a true coldwater species or prefer warmer water.

True coldwater species like salmon, trout and whitefish enjoy water temperatures in the 40s. They frolic with icebergs and rarely venture above the thermoclines in the summer.

When the lakes cool in the fall and the thermoclines become less defined, these large coldwater predators are free to roam and they frequently head for the shallows.

Coldwater predators heading for the shallows was the premise of last month’s column, ‘Twas the Night Before Fishmas.

Species that prefer their water on the warmer side, includes crappie, minnows, muskie, perch, pike, smallmouth bass, sunfish, and walleye. This group never ventures below thermoclines if they can help it and if given the option to overwinter in the freshwater springs of the Florida panhandle, they might take it.

Since traveling south for the winter is not an option, they seek out the warmest safest waters they can find. Minnows tend to stay near shore huddling together under logs, branches and other shallow water debris.

Although, these bait fish would likely prefer the slightly warmer water near bottom, they usually sacrifice temperature for safety and shelter in shallower water to avoid the increased threat from the coldwater predators.

The yellow perch would bask in a Florida spring all winter, given the chance. They love warm water which is why the shallower areas like Green Bay, Saginaw Bay, Lake St. Clair and the Western basin of Lake Erie are all renowned for perch.

Perches thrive in the warm shallows all summer but also stay shallow in the winter. They have a high food drive, their main food source being minnows, that also keeps them in the shallows. Plus, the depths are thick with predators.

Larger warmer-water predators like bass, muskie and pike slowdown in the winter and drop down into the slightly warmer water near bottom. Their digestion slows, taking them longer to digest the food they do eat which allows them to hunt less. They literally just chill out.

There are other winter survival strategies Great Lakes fish employ.

For instance, log perch and round goby overwinter by burrowing under rocks where they basically hibernate all winter.

Shiners in shallows. (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

North wind effect

The most obvious effect of wind on water is waves. But wind also plays a significant role in water temperatures and its impacts reach all the way to the bottom.

Shallow water bays and the entire western end of Lake Erie never develops thermoclines. In those areas, the wind acts like a giant mixer keeping the top and bottom layers blended.

So, the wind prevents thermoclines from forming in shallow water and it also moves the deepwater water ones.

When a big summer storm blows it can push the surface water to one side of the lake. This is called a seiche, and this movement also drives deeper water up to the surface.

If you have ever enjoyed a warm swim in the Great Lakes in August and jumped in the following day to a lake that felt ice-cube cold, you have experienced the effect of a seiche.

For the yellow perch basking in an 80 degree bay, the sudden upwelling of icy water is not appreciated.

On the other hand, the salmon that have been essentially locked below the thermoclines for months. They are thrilled to follow the colder water stream, right up into the shallows full of grumpy yellow perch and shivering sunfish.

That is the kind of day when the anglers catching salmon off the Ludington pier can be heard saying, “Great fishin’ today. The lake flipped.”

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

I Speak for the Fish: ‘Twas the night before Fishmas

I Speak for the Fish: Carp are crazy about corn

Featured image: Fall salmon. (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

2 Comments

-

When winds are from the north, much of the water below the surface will be pushed toward the west due to a process known as the Ekman spiral. When warm water gets pushed away from our beaches, cold water from deeper in the lake will take its place.”

-

Very interesting article for the public. As a fish biologist, I want to share that trout, salmon and white fish are considered cold water, species, while perch and walleye are considered coolwater, species, and bass and bluegill are considered warm water species. by the way, while Trout and salmon are active at 32°, their optimum temperature is actually 59°. Thanks for explaining thermal inversions to folks.