By Enrique Saenz, Indiana Environmental Reporter

Federal funding mechanisms for improving Indiana’s water infrastructure work but need more flexibility to help eliminate lead service lines, PFAS and other issues, according to testimony from one of the state’s top finance officials.

Jim McGoff, Indiana Finance Authority chief operating officer and director of environmental programs, testified March 29 before the U.S. House Subcommittee on Environment and Climate Change of the Committee on Energy and Commerce.

McGoff was one of four witnesses called to testify on how the federal government could best facilitate the distribution and use of about $43 billion in water infrastructure funding provided by the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

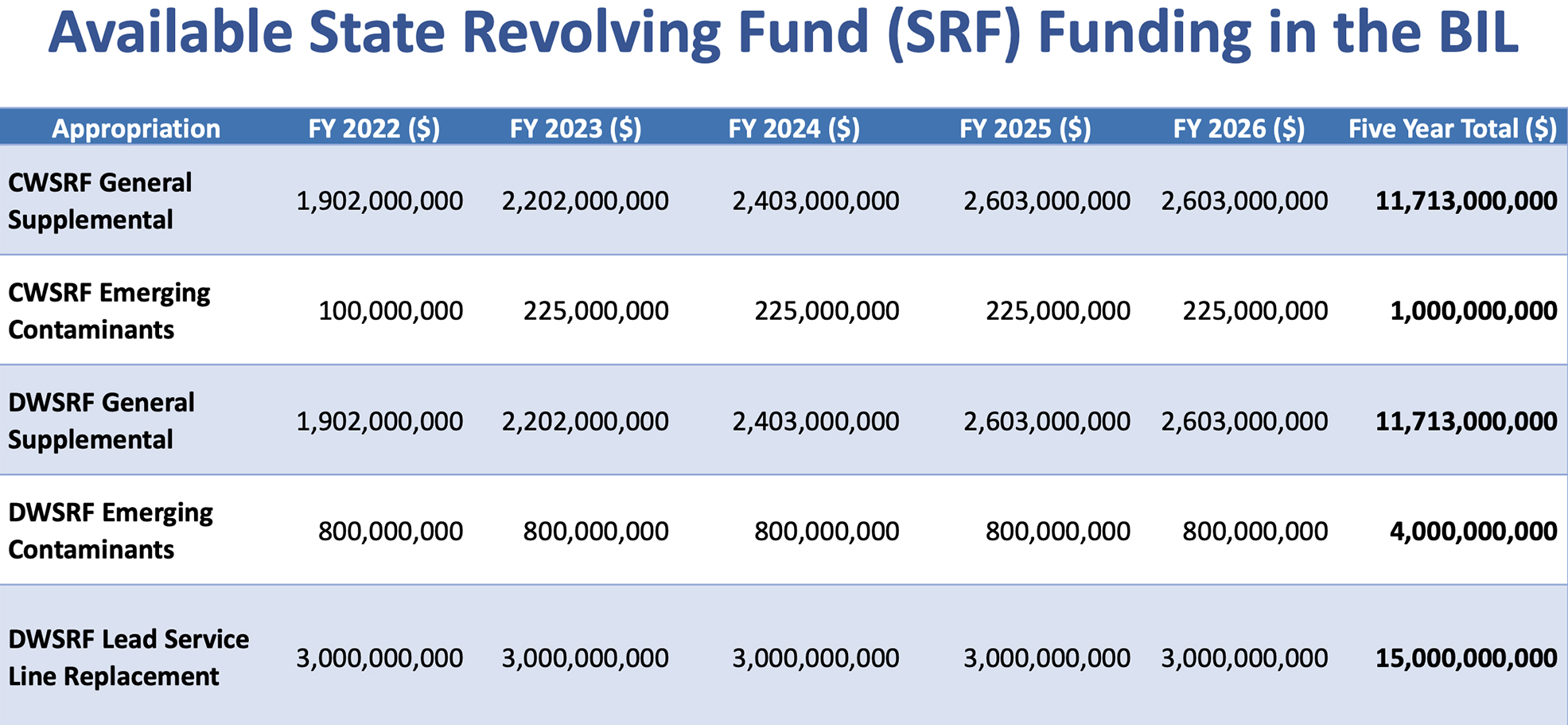

The money will be distributed through the Clean Water and Drinking Water State Revolving Funds, a federal program managed by states that provides low-interest loans and grants to communities needing to improve their wastewater and drinking water infrastructure.

The clean water and drinking water programs will each receive $11.7 billion to disburse among the states. The funding includes $15 billion for lead service line removal and $5 billion to address PFAS and other emerging contaminants.

McGoff said the program is effective, but requires some changes to effectively tackle water infrastructure challenges.

“I can confidently say the SRF programs are experts in providing low-cost financial assistance for every community’s drinking water needs. Congress is right to choose the SRF programs when looking for the appropriate vehicle to address emerging contaminants and lead service line removal,” McGoff testified. “However, to be able to achieve the intent of the law, this targeted funding requires a more flexible and innovative approach than the base program that we currently monitor.”

McGoff said the program’s rules sometimes conflict with its intent, preventing the IFA from funding some efforts to address public health threats despite the clear benefit.

Source – EPA

He said the IFA was not permitted to use emerging contaminant funding to remove PFAS firefighting foam from fire stations in Indiana, an act that would prevent PFAS chemicals from making their way into waterways, because SRF rules require the financial assistance to go directly to a drinking water utility.

Over 9,000 PFAS chemicals exist, but only a few have been thoroughly studied. Those PFAS chemicals have been linked to serious health conditions like increased risk of kidney and testicular cancer, increased cholesterol levels, increased risk of high blood pressure and others.

Firefighting foam made with PFAS, known as aqueous film forming foam, has been used for decades to fight fires involving petroleum and other flammable liquids. The foam was found to leach PFAS chemicals into soil and waterways, potentially exposing people close to and downstream from the site the foam was used.

The chemicals do not degrade in the environment and remain in the human body for at least five years after it enters.

Indiana lawmakers banned the use of PFAS firefighting foam for training in 2020.

IDEM later tested some community water systems throughout the state for several PFAS chemicals, finding evidence of them in at least four systems.

It’s unclear whether other PFAS chemicals exist in Indiana waterways or on land that threatens the waters.

McGoff said that unless the federal government is flexible in how PFAS funds are used, states may never get the chance to find out.

“An SRF program has used its clean water SRF funds to fund energy efficiency projects with EPA approval, under the theory that energy efficient addition to homes would reduce energy use, which would reduce energy production, which would reduce stack emissions, which would reduce particulate matter leaving the stack and falling into a receiving stream,” McGoff testified. “Arguably, there’s a greater threat of a container of firefighting foam failing and leaking in the basement of a firehouse, or the more likely scenario of it being used and then flowing into a receiving stream or well that may be the only the town’s only source of drinking water.”

The state runs its own voluntary PFAS firefighting foam collection initiative through the Indiana Department of Environmental Management and the Indiana Department of Homeland Security. The initiative collects PFAS foam from fire departments willing to rid themselves of their stockpiles at no cost to the departments.

McGoff, who also serves as president of the Council of Infrastructure Financing Authorities, said increased flexibility would also help address lead service lines in the state.

Lead contamination has long been a threat to the health of Americans. Lead gasoline, paint and plumbing were all legal to sell and use until the late 1970s.

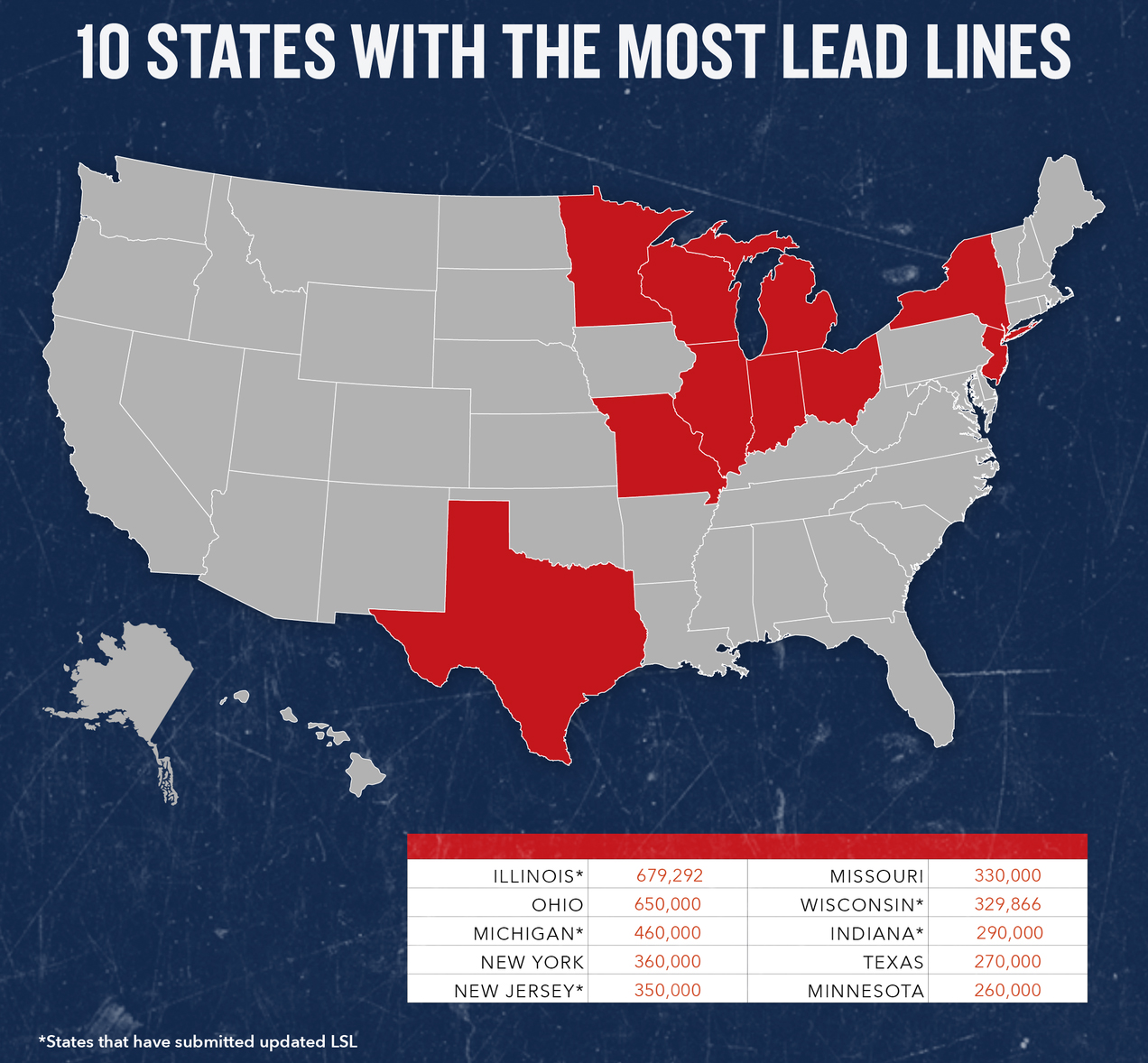

But Indiana residents and other Rust Belt residents experience a greater threat from lead service lines than other areas.

Source – NRDC

A 2016 survey by the American Water Works Association estimated about 6.1 million lead service lines in all 50 states combined. The region including Indiana and neighboring states was estimated to have the largest number of lead service lines in the nation.

But no one really knows how many lead service lines actually exist in Indiana or elsewhere.

The IFA funds a statewide voluntary lead-testing program in public schools, which found that in the 2017-2018 school year, 62% of schools tested had at least one fixture detected with lead levels over 15 parts per billion. Hundreds of schools did not participate in the program.

In 2020, Indiana lawmakers passed a law requiring schools to test their buildings for lead contamination by Jan. 1, 2023.

Outside of schools, the extent of contamination continues to be unclear.

According to Gabriel Filippelli, director of the Center for Urban Health at Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis, communities only started mapping service line construction in the 1970s and 1980s.

“We actually have absolutely no idea where most of these service lines might be. I think we have a very inadequate understanding of the distribution of lead in soils, paint and water. And, clearly, we can’t test 5 million soil samples around the state. It just doesn’t work that way,” Filippelli told the Indiana Environmental Reporter in November, soon after the infrastructure funding was signed into law.

McGoff said current State Revolving Fund rules prevent states from investing allocated funds into serious investigations of where lead service lines exist.

Federal law currently requires that states provide the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the agency that runs the state revolving funds, a list of projects they intend to fund before they can begin spending a single dollar of allocated funding.

“Therein lies the problem. Utilities in many states have not begun the process of developing an inventory of lead service lines. It would be logical to think we would be able to use these funds to generate a statewide inventory and then begin the process of removing the lead lines. However, we are limited to only using a fraction of the funds for this purpose,” McGoff testified.

McGoff told the subcommittee that funds called “set asides,” which are generally reserved for administrative expenses, and state-specific initiatives may be eligible, but would not be sufficient to complete vital lead service line inventories.

“Logic suggests, and we believe your intent would be, that the lead service line funding be eligible for use in all things associated with the removal, or at the very least, the first and second year of funding be eligible for inventories, believing that once inventoried, the latter years funding could be targeted for their removal,” McGoff said. “We do not believe wholesale changes to the legislation are necessary. It’s good legislation. But minor revisions are needed to ensure we can achieve its goals.”

At least 49% of the SRF funding for clean water and drinking water must go to “disadvantaged communities,” a term each state has the power to define according to their state’s needs.

“In Indiana, we have both urban and very rural communities, and so our disadvantaged community definition recognizes very low median household income and high user rates,” he testified.

McGoff said the state targets grants and forgivable loans to disadvantaged communities.

The state’s aging infrastructure and climate change-altered rainfall patterns have prompted more communities to apply for grants and other help from the IFA.

A state audit found that many service lines in Indiana are nearing or have already reached the end of their service life and need to be replaced at the cost of $2.3 billion, and $815 million annually for maintenance.

Climate change is adding pressure to already stressed existing water systems by causing precipitation to fall in shorter, heavier events, increasing the likelihood of combined sewer overflows, a threat to public health.

More than 500 communities applied for funding from the IFA’s State Water Infrastructure Fund, a program that uses allocated state funding and Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds to finance projects to improve the state’s water resources and provide “substantial rate relief” to Indiana utility customers the state said are most in need of help.

So far, the state has issued 22 SWIF grants during the first of four rounds of funding. The IFA said it will open up applications for the next round of funding this summer.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Researchers find wetland plant can filter PFAS chemicals

Indiana University study links lead exposure to juvenile delinquency

Featured image: Indiana Finance Authority chief operating officer Jim McGoff was one of four witnesses that testified at the U.S House Subcommittee on Environment and Climate Change of the Committee on Energy and Commerce March 29. (Photo Credit: Indiana Environmental Reporter)