I’ve been outsmarted by more than one species.

A red fox in a Florida nature preserve comes to mind. I observed the fox entering a den and spent two hours patiently waiting for it to emerge so I could take its picture – only to discover the clever fellow had exited out the back shortly after I parked myself out front.

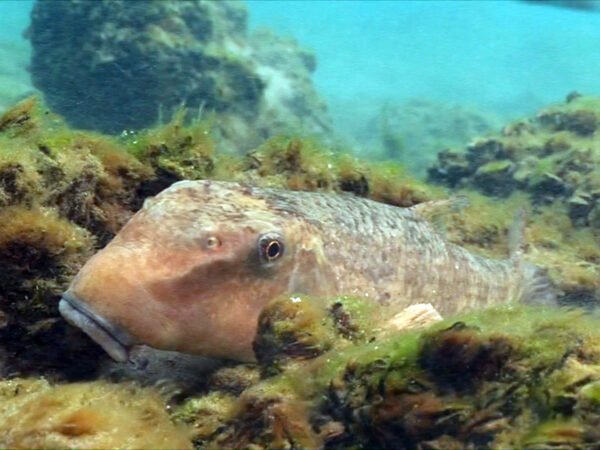

A grouper in the Caribbean gave me a similar ditch during my one and only attempt at spearfishing.

I watched the grouper duck into a small cave on the reef and thought I had it cornered. I took a deep breath and dove down to the entrance of the coral cave. But the only thing I found was a 3-foot-long, mildly irritated green moray eel, the grouper having long since exited out the back of the reef.

The fox and grouper both perceived me as a potential threat and took evasion tactics. In the wild, when survival often depends on the ability to avoid hungry predators, it pays to err on the side of caution.

Another species that comes to my mind when I think of uber-smart avoidance is the duck. Our first attempt to film them from underwater proved to be a case study in waterfowl awareness and diligent avoidance of predators.

The idea began when my husband and I were watching a pair of grebes swim across a small pond. The tiny birds moved so quickly across the water that they caused a wake. I figured their little webbed feet had to be churning below the surface.

How cool would it be to see and film that?

We immediately began a duck filming plan.

We selected a filming location along the Thomas Edison Parkway in Port Huron where the St. Clair River is about 15 feet deep. We wanted it deep enough for the ducks to feel safe, but shallow enough that Greg could zoom in on their feet just beneath the surface.

We figured 15 feet was enough depth since we planned to film mallards. These ducks are called dabbers because they only submerge their head and necks underwater when they feed. Unlike mergansers or cormorants – which we occasionally see cruising along the river bottom looking for food – mallards never truly leave the surface.

Mallards offered two additional benefits. For one thing, they are the most abundant duck in North America. In 2014, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service estimated the North American population at 11.6 million breeding birds.

And a mallard’s feet are bright orange.

We waited for a sunny afternoon when the water clarity was over 20 feet and the rocks on the river bottom were visible from the boardwalk.

Greg got in and laid motionless on the river bottom while looking directly up at the surface. From the top of his hooded head to the tips of his jet-propulsion fins, his gear was uniformly matte black. His camera system was an equally benign matte grey.

To our eyes, nothing about him seemed overtly threatening. We thought he would appear to the ducks as just another shadowy spot on the distant river bottom.

The current carried Greg’s bubbles a good 25 to 30 feet downstream before allowing them to break the surface. We knew this would ensure his exhalations did not rise straight up and pop right under the birds which was sure to scare them away.

We were hoping the downstream bubble drift would help to disguise Greg’s true location.

Once Greg was in position my job was to encourage the resident flock of mallards and ring-billed gulls to leave their green parkway perches for the river’s clear blue waters. I used seed pellets from a local feed store as incentive.

Mallards are omnivores which means they are not picky eaters. My Audubon field guide lists their diet as including all kinds of aquatic plants from pondweed to wild celery, aquatic insects from mayflies to scuds, terrestrial grasses and seeds like acorns, and all forms of protein from tadpoles, frogs and small fish to earthworms.

Basically, everything but the sliced bread that people like to feed them even though it is not good for them.

The grain pellets we purchased are designed to initially float then slowly sink as they become more saturated.

Luckily for us, the perpetually hungry ducks liked the pellets enough to jump into the St. Clair River to retrieve them.

I got the whole flock floating a good 50 yards upstream of Greg’s position. And as expected, the river quickly carried the birds straight downstream toward the camera.

Duck swimming beside sunfish. (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

As the first birds drifted over Greg, I watched a male stick its emerald-capped head underwater.

It looked straight down at Greg.

A split second later, the duck snapped his head out of the water and started screeching and honking. I’m not fluent in mallard, but there was no mistaking his alarm.

The entire flock reacted with the same frantic flight response as tourists at the beach when someone yells shark. Within seconds, every bird was in the air and no amount of coaxing on my part would get them back in the water that day.

The mallard’s fear upon seeing a large, dark, unfamiliar object directly below reflects an important survival skill.

Ducks and other waterfowl need to be wary of predators that attack from below. Muskie, pike and even large snapping turtles are known to hunt and eat birds.

The ducks need to constantly monitor their surrounding for danger and that includes things attacking from underwater. Birds cannot afford to take chances and they don’t. Which meant filming them from below was probably not going to work.

So, we devised a new plan.

This time there would be no diver, no bubbles and we hoped no threat with one little GoPro camera on a pole.

We picked a new location at a small inland lake with a public park and another resident flock of mallards. We set up at the end of a floating pier. Greg rigged our GoPro to a long pole with a 90-degree bend that allowed him to extend the camera 8 ft out from the pier.

We thought the ducks would feel safer further away from the pier and us.

Using the same pellets, we gradually moved the flock from the shoreline toward the submerged camera at the end of the pier. Everything was fine until the ducks got about 10 feet from the GoPro.

That’s where they stopped.

And they would not swim directly over the camera.

We were feeling defeated again until the sunfish showed up and changed the dynamic.

Our failed attempt to lure the ducks over the camera had successfully gained the attention of the lake’s abundant population of pumpkinseed sunfish.

The sunfish had no fear of the camera rig, and the large school eagerly began to devour the duck pellets.

Once the fish were above the camera, the ducks finally moved in and began to feed.

As long as there were at least half a dozen sunfish between the surface and the GoPro, the ducks paddled back and forth directly over the camera. But when the fish scattered, so did the ducks.

Even after multiple visits on different days, the mallards never swam directly over the camera unless there was a layer of fish below them.

It’s kind of a brilliant survival strategy.

The ducks basically use the fish as an insurance policy. By keeping another species between themselves and the potential treat, the ducks reduce their risk of dying from a surprise attack.

We did eventually get some usable footage of bright orange webbed-feet paddling around. And it is very cute.

But every single frame also contains at least one sunfish.

I’m not embarrassed to admit that when it comes to matching wits with other species in the wild, it’s fair to say I’ve been schooled by some of the best.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

I Speak for the Fish: Logperch rocking, rolling and rebounding

I Speak for the Fish: Meeting the mysterious muskie

Featured image: Duck swimming beside sunfish. (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)