The gold medal winner of this year’s annual San Francisco Chronicle Wine Competition was a light unoaked chardonnay from Debonné Vineyards – a vineyard located in the Lake Erie region of northeast Ohio.

Despite the American wine and grape industry’s association with California’s Napa Valley, the Great Lakes region boasts four of the top 10 wine producing states in the nation.

New York produces 32 million gallons of wine annually, making it the third largest wine-producing state. Pennsylvania, Michigan and Ohio round out the top six wine-producing states.

Wine can mean big business for local economies. In Ohio, the wine industry is responsible for creating over 8,000 jobs and generating $1.3 billion in annual revenue. Michigan’s wine industry is growing as well with over 150 wineries across the state.

Even Wisconsin, which is not in the top 10 producing states, is benefitting from its burgeoning wine tourism sector. The wine and grape industry in Wisconsin brings in a total of almost $120 million in annual revenue with roughly $42 million coming from tourism-related activities, according to a study conducted by the University of Minnesota Extension.

And the soil conditions of the Great Lakes play a big role in that – you cannot make wine without grapes.

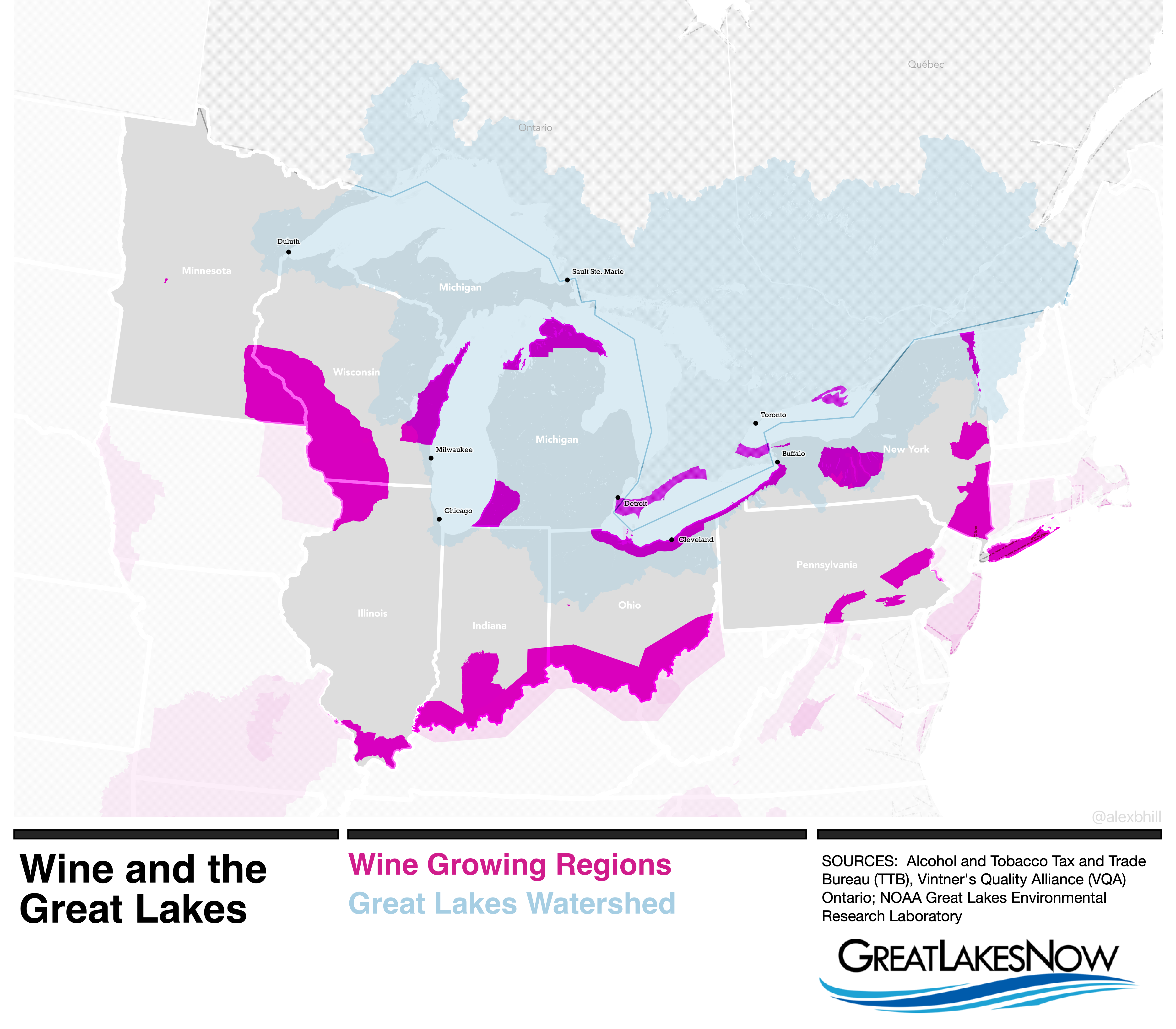

Map of wine growing regions around the Great Lakes (Image created by Alex Hill for Great Lakes Now)

One big wine-growing region is the Niagara Escarpment, a specific sub-region around the Great Lakes known for its porous soil. The Escarpment spans from eastern Wisconsin to upstate New York, and its rocky conditions allow for good drainage, giving heartier grape varieties an opportunity to thrive.

But the soil is just one component contributing to a robust grape industry around the Great Lakes. Climate also plays a role. The well-known lake effect cold prevents an expedited budding cycle of the grape, while the warmer falls extend the growing season.

“For a long while, it was thought the climate in the Midwest was too harsh for the more tender vinifera – and it still is for some varieties,” said Donniella Winchell, executive director of the Ohio Wine Producers Association. “But many of the ‘cooler climate’ varieties like chardonnay, riesling, cabernet franc, showed some promise, especially when planted around the Great Lakes, which provided winter temperature moderation and delayed spring bud break as a foil to killing frosts.”

The areas around each of the Great Lakes tend to be suitable for different types of grapes. Lake Erie is known as the leading concord grape-growing region in the world while the climate off the northeastern coast of Lake Michigan creates perfect growing conditions for grapes such as sauvignon blanc and riesling.

Vinifera, otherwise known as the common European grape variety used to make wine such as chardonnay, cabernet sauvignon and pinot noir, is more difficult to grow in many parts of the Great Lakes region because it does typically need warmer conditions.

Lake Erie’s colder, longer winters are “pretty tough on vinifera and some of the less cold hardy hybrids,” according to Bryan Hed, research technologist at the Penn State Lake Erie Grape Research and Extension Center.

“There is some vinifera here, but I think we probably have a harder time getting red vinifera ripe up here compared to the southeastern part of the state where there is more heat and a longer growing season,” Hed said.

Concord grapes grown at a Pennsylvania State University experimental vineyard at the Lake Erie Regional Grape Research and Extension Center in northeast Pennsylvania. (Photo courtesy of Pennsylvania State University)

Breeding solutions for more grapes

To address the frigid temperatures of the Upper Midwest, a group of hybrid grape varieties were developed by grape breeder Elmer Swenson in Minnesota during the mid 20th Century.

Cold climate variety grapes are defined by how well they can survive winters. Cool climate ones are known by how well they can survive winter in comparison to warmer climate varieties such as vinifera. For context, a cold climate variety can survive in temperatures up to -30 degrees Fahrenheit while cool varieties can only survive in temperatures up to roughly -6 degrees Fahrenheit.

Swenson is viewed by many as a pioneer in breeding cold climate grapes. While he is not the first to make strides in cold climate grape research, he made a name for himself by breeding grapes that could be used in wine blends. For example, his St. Pepin and Lacrosse hybrid grape varieties are used in wine that has a sweet taste similar to riesling. Swenson’s St. Croix hybrid is used in making red and rose blends and is low in tannins. St. Croix is likely the most frequently used cold climate variety grape to make wine. It has spawned popular wine brands across the Midwest, including wine made in Nebraska, Iowa and of course Swenson’s own Minnesota.

The efforts from individuals like Swenson and academic centers like the Lake Erie Grape Research and Extension Center are far from the only to study and develop the industry in the Great Lakes region. Michigan State University has a viticulture program, University of Minnesota is home to a grape-growing enology program, and the University of Wisconsin Fruit Program also studies grapes.

Over the years, with research from Michigan State, Ohio State, Perdue and Cornell, among others, wineries in the Great Lakes region have been able to improve growing conditions through careful site selection to take advantage of a variety of elements including slope, sun exposure, air and water drainage, as well as soil types.

Researchers have also helped grape growers innovate their practices to maximize the region’s soil and climate conditions. Findings by the grape researchers in Ohio have helped implement row tiling in Ohio, which keeps the grape roots dry. Research led to wind machines being used to blunt the impact of temperature inversion, which can cause freezing air to be trapped under warm air. Left unattended, that freezing air could damage or destroy the grape vine.

“As a result of those discoveries, we are now planting varieties like cabernet sauvignon, pinot noir, pinot gris, etc., along the Great Lakes’ shorelines that a dozen years ago were a pipe dream to most vineyard managers,” Winchell said.

Catch more news on Great Lakes Now:

Tips, Tricks, Recipes: Want to know how to eat Great Lakes fish?

Great Lakes Trails: Relief funds spark new investments into outdoor recreation

As Drought Grips American West, Irrigation Becomes Selling Point for Michigan

Featured image: Concord grapes grown at a Pennsylvania State University experimental vineyard at the Lake Erie Regional Grape Research and Extension Center in northeast Pennsylvania. (Photo courtesy of Pennsylvania State University)