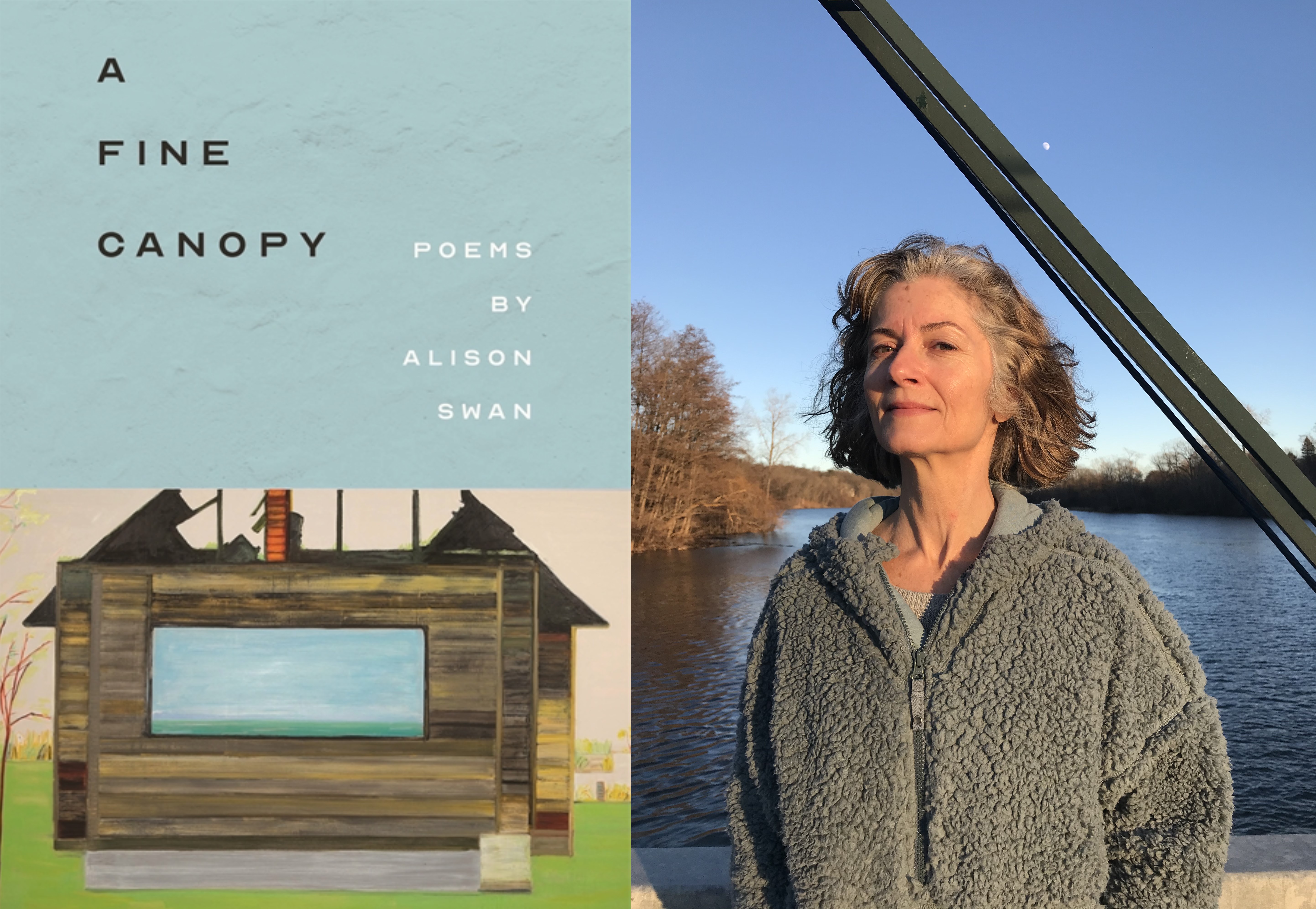

In a Great Lakes world dominated by policy proclamations, fights for funding and the never-ending conflict between the triad of politicians, business and environmental interests, Michigan poet Alison Swan operates on a different level.

Fully cognizant of these struggles, Swan engages them on a human and experiential level through her poetry by calling “the reader to witness, appreciate and sustain this world before it becomes too late,” as described on the cover of her new book, “A Fine Canopy.”

“A Fine Canopy” is a collection of poems based on Swan’s life-long personal experiences, diverse locales where she has lived and material collected over decades.

A 1986 book on the declining state of the Great Lakes prompts Swan to write “shores erupt in built things that have never held a seed.” She processes her feelings about Detroit’s decline and evolution in a poem simply titled, “Detroit.”

Senior correspondent Gary Wilson recently talked with Swan about “A Fine Canopy,” the state of Michigan’s sand dunes and the current state of Michigan’s waterways. Swan also shared her thoughts on National Geographic’s recent widely-publicized Great Lakes feature.

The interview was conducted on the phone and via email. It was recorded, transcribed and edited for clarity.

Great Lakes Now: You are described as “an Eco Poet whose writing shows her advocacy for natural resources.” Can you elaborate on “eco poet” and how it translates to “A Fine Canopy?”

Alison Swan: It’s a great question because it provides an opportunity to let you know that I didn’t choose the label ecopoet and I don’t use the phrase natural resources.

Alison Swan (Photo Credit: David Swan)

In 2021 it feels like people who talk about eco poems and eco poetry emphasize environmental awareness. In other words, a poet who is writing an eco poem is writing a poem that shows awareness of the multiple crises that the Earth is facing right now in terms of what we call nature, a word we might need to reclaim.

I don’t label myself and hardly ever call myself a poet actually.

Eco poet is a newer term, the cool kids way of describing nature poems. I don’t think nature poems can be written in the 21st century that don’t show awareness of crises. I’d say they’re fantasy rather than nature poems. I don’t use the phrase natural resources because I don’t think of land as a resource first, I think of it as habitat. If I were to characterize my work, I’d say I write poems of inhabitation.

GLN: While firmly rooted in Michigan now, you lived in Florida, Boston and Seattle earlier in your life. You say every poem you’ve written owes a bit of its existence to peninsulas in Michigan, south Florida and the Pacific Northwest’s Olympic Peninsula. Is there a common thread between these locales or are they unique in how they inspired you?

AS: Peninsulas are powerful landforms because they are places where water and land come up against each other in ways that humans can experience easily.

The weather in Michigan’s peninsulas, the weather of south Florida and of the Olympic Peninsula are very much impacted by how much water surrounds them. They are dynamic places in terms of ecology, weather and climate. I was attempting to inhabit them, trying to know and have them be part of what it means to be a human on Earth. I didn’t just passively reside in those places. I was engaging with them as places, as habitats.

Read more on Great Lakes Now:

“Saving the Great Lakes”: National Geographic December issue explores the lakes and their struggles

Lifeblood: Photographer shares the Lake Erie connection uniting shoreline residents

The Best Part of Us: Great Lakes author tackles conflict and culture in new novel

GLN: The first poem in the book is titled, “After Reading The Late Great Lakes.” It refers to a 1986 book titled “The Late Great Lakes” by William Ashworth that focused on our apathy toward the condition of lakes. The poem talks about parceling real estate and shores that “erupt in built things that have never held a seed.” Why did you lead with that poem?

AS: The recent National Geographic feature article on the Great Lakes titled “So Great, So Fragile” caught my attention. The subtitle reads, the Great Lakes “helped make the United States an agricultural and industrial powerhouse. But now climate change, pollution and invasive species threaten the continent’s most valuable resource.”

Now? As opposed to when? There is nothing whatsoever new about any of these threats and they have all been well documented—for decades.

I led with the poem because it describes my deepest concern as a human alive in the 21st century. Human beings by and large do not seem to recognize that what we do to land we do to water, and when it comes to the Great Lakes we seem to be particularly blind. And what we do to land and water we do to ourselves—and evidence of our missteps is everywhere. All we have to do is look to that very land and that very water for information on how we might better proceed than the way that we are now.

GLN: The poem simply titled “Detroit” talks about scrub brush reasserting itself and how so much that was there has been undone. What’s happening in this poem?

AS: What I’m doing in “Detroit” I think is maybe writing through a bit of the tension I feel when I reflect upon my concern for the people who live there now and my conviction that we cannot simply build the city back the way it was when my grandparents raised their children on the East Side. Can urban farms play an important role? Can wild nature? I think so. Does everyone want to live next to a farm or a natural area? Maybe not.

There’s a fun story behind this poem though. Twenty-five years ago now I was listening to a radio report about what was then called urban farming in San Francisco. I went on high alert because at that point it wasn’t a trendy or talked-about subject. One of the people the reporter interviewed was a 12-year-old boy who had grown up in the city who had hands-on experience with farming in the city. The reporter asked him what he learned from the experience and he responded, “asphalt isn’t forever.”

I wrote that down and put it on my bulletin board and lived with it for literally two decades before I started doing anything with it. Then I watched a documentary about urban farming in Detroit and one of the Detroiters interviewed for the film was asked how he felt about having chickens and goats in his neighborhood. He was open to it and unfazed by it at the same time. He said, “It’s totally illegal and no one complains. What’s there to complain about?” That made me remember the card on my bulletin board that said asphalt isn’t forever and I thought I had the beginning of a poem.

What I believe strongly from what I’ve experienced in my life so far is that tending to plants and animals is a way to connect with the land in ways that we’ve lost. And when I say we, I mean human beings in general in this country on this continent. At the risk of sounding facile, it’s an easy way to heal.

GLN: A reviewer described “A Fine Canopy” as “restorative reading.” Was that your intent?

AS: I am going to be honest with you. I don’t think I had any intention for this book other than to make something that was fresh and engaging. And also factual when it comes to the natural world. I enjoy it when people describe this book as restorative. I’ve had people say that it’s comforting, and I had a good friend tell me that the night of the election instead of watching TV she read my book.

GLN: You have written about Michigan’s sand dunes and have been active in advocating to protect them. What’s the state of the dunes today? Are they still threatened by development or has that passed?

AS: The sand dunes of the Great Lakes are in more danger than ever because under the administration of the former Gov. Rick Snyder, quite a lot of teeth were removed from regulations that were protecting the dunes, along with a long list of other things. In the last four years it’s been more of the same. The situation at the mouth of the Kalamazoo River is, I would say, dire. It’s dire as a direct result of deregulation and pandering to profiteers, really.

GLN: Has Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s administration in its two years done anything to lessen the threat?

AS: I don’t think so. Although, I have to acknowledge that having Gov. Whitmer is a vast improvement and it remains to be seen what she will accomplish given the state legislature that she has to contend with.

GLN: With a long view of how Michigan has treated its waterways under both political parties, are you optimistic that lessons have been learned from past neglect? Or is an environmental recovery still generations away?

AS: Oh boy, I guess I believe in rapid and sudden change and the possibility of it. That’s the way it happens sometimes, though rarely in the natural world.

Sometimes there are cataclysmic events that cause massive change quickly. What we need in mainstream human civilization on Earth right now is a similar about-face. I’m so grateful to all the people who are doing the work who might make that happen. But I don’t think it’s a foregone conclusion that we will make the changes we need to make as quickly as we need to make them. We’re perfectly capable and I believe we know what we have to do, we just need to do it.

Information on A Fine Canopy is available at Wayne State University Press. More on Alison Swan can be found here.

Catch more news on Great Lakes Now:

Michigan cities must begin replacing lead pipes. But who has the cash?

Unexploded Ordnance: Lake Erie shoreline site of long-term munitions study

API key not valid. Please pass a valid API key.