Generations of a family led by a strong patriarch clash over the future of a treasured Canadian vacation home. The local Ojibwe chief threatens to claim the land.

And a pristine but foreboding lake north of Lake Huron is an omnipresent part of the drama.

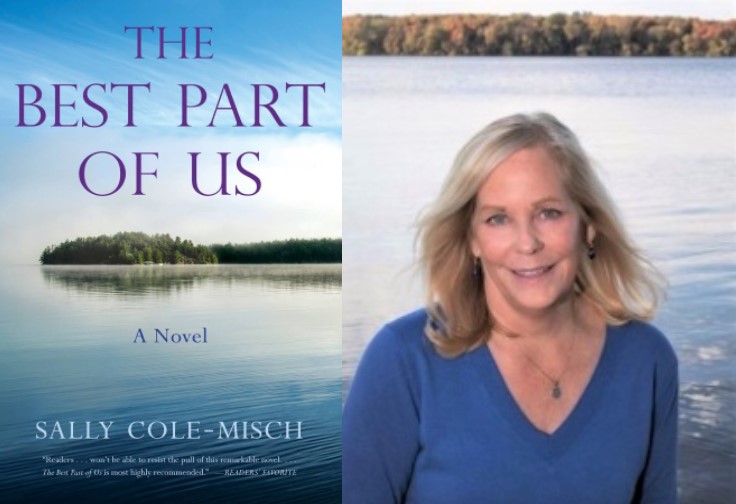

That’s the setting for The Best Part of Us, the debut novel by former international Great Lakes executive, Sally Cole-Misch.

A self-described “environmental communicator,” Cole-Misch is a former public affairs officer with the International Joint Commission, the U.S. and Canadian agency that advises the two countries on trans-border water issues, including the Great Lakes.

She lives in greater Detroit.

Part of her work for the IJC was to communicate our connection with nature and the role we all play in restoring and protecting the gifts that nature provides.

That in turn influenced the creation of her book which, though it is set in the Great Lakes region, is fictional.

Great Lakes Now senior correspondent Gary Wilson recently talked with Cole-Misch about the impact nature has on life events and how disparate cultures deal with issues that go back centuries.

The interview was recorded, transcribed and edited for clarity.

Great Lakes Now: The plot for The Best Part of Us exists at the intersection of family connection and conflict with a looming culture clash. The environment and the natural world are often in the foreground. What attracted you to this mix?

Sally Cole-Misch: I wanted to write a novel where nature was as much a character as the people in the story, because we are all part of the same universe and interconnected with nature every day, even if we don’t realize it. I wanted it to feature a family whose connection is strong but also has conflicts.

Sally Cole-Misch (Photo courtesy of She Writes Press)

Because of my previous work with Indigenous peoples, I couldn’t imagine writing a Great Lakes-based novel without including them. I wanted their role in Great Lakes history and their cultural connection to the land, water and air to be a part of this story.

GLN: Why did you choose the Canadian setting north of Lake Huron? What attracted you about this location?

SCM: Part of it is my family history, as we visited that region when I was young. I think Lake Huron is often the forgotten Great Lake. We all know about Lake Michigan and Lake Superior’s majesty. But the Canadian Shield country is gorgeous, so it was easy personally to write about it.

GLN: In a dispute between Indigenous people and descendants of European settlers, the book takes on the issue of ownership and property rights of natural places. Can anyone really own a natural place or is society still grappling with that issue?

SCM: We are still grappling with the ownership of nature issue and that’s part of my reasoning to raise it in this book. Because Indigenous communities around the Great Lakes have been here for thousands of years, you can argue that they have an inherent right to the land, and yet that land has been either taken or sold over time to other people who feel they have a right to it. But it’s part of the same overall scope of nature and perhaps sharing is a better resolution.

GLN: The book is rich in references to the natural world like “these trees, this land and water, all of this is my family too.” How do you see the connection between nature and people?

SCM: When you look at the studies, nature provides so many benefits that help our physical and emotional wellbeing. Being in nature helps to lower blood pressure and stress. It reduces anxiety and gives us a sense of generosity and commitment to something larger than ourselves.

I also wanted to write a story to help readers remember a special place or part of nature that they hold close in their heart. A place that will help them consider the valuable and essential roles the natural world holds in their lives.

GLN: Another natural world reference is “I’ve learned that nature always has the last say. Once you accept that you can relax and start to see its magic.” Can you elaborate?

SCM: We all know that nature does have the last say whether it’s a tree that falls in your yard following a storm or the fluctuating high water levels around the Great Lakes. We can’t control Mother Nature and we shouldn’t try to. We need to understand, as Indigenous cultures do, that it’s up to us to adapt and become resilient to nature’s changes.

In the book’s dedication I quote Ralph Waldo Emerson where he says, “If the stars should appear one night in a thousand years, how men would believe and adore.” I think that’s true.

Rather than taking for granted that the stars and nature will always be here, separate from us, we can embrace how magical our world is and that we are a part of that world. When we recognize this, we will think twice about actions that aren’t sustainable for the planet, and thus for ourselves and our children as well.

GLN: Given your tenure at the International Joint Commission, we’d be remiss if we didn’t ask about the state of the Great Lakes. How do you see the trendline for the health of the lakes?

SCM: I see positives as far as funding for the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative and similar funding mechanisms in Canada in the last few years. Some state, local and provincial governments are instituting creative projects. I’ve seen a tremendous amount of citizen commitment and a sense of urgency about the issues facing the Great Lakes.

On the negative side, there has been an unrelenting reversal of environmental protections in the U.S. in particular, and in Canada the federal and Ontario provincial governments have very different environmental priorities.

When I compare the 1980s and 1990s when I was first at the IJC to now, there has been a drastic decline in the level of coordination and cooperation between the two countries. I fear that this doesn’t bode well for the Great Lakes in the future.

The Best Part of Us is scheduled for a Sept. 8 release. More information at She Writes Press.

Read more Q&As on Great Lakes Now:

Eastland Documentary: Filmmakers talk behind-the-scenes journey and stories

Turtles vs. Oil: Great Lakes Now producer talks ecosystems, life on the water and covering the lakes

Wetland Wisdom: Documentary looks at breakthrough in Great Lakes wetland research