TRAVERSE CITY, Mich. (AP) — Clare Nagrant earns her living from tourism, so she’s taken a beating during the coronavirus-imposed shutdown. A few months ago, she was juggling four jobs. Now she’s down to one part-time gig with a distillery that stayed open by adding hand sanitizer to its product line.

Yet the 42-year-old single mom doesn’t feel the usual excitement about thousands of free-spending summer visitors flocking to northern Michigan’s lake country, even though its restaurants, taverns and shops are being allowed to reopen this weekend.

“I feel like I’m between a rock and a virus,” Nagrant said after Gov. Gretchen Whitmer loosened restrictions on some businesses in northern Michigan, which has had far fewer COVID-19 cases than Detroit and other cities in the southern part of the state.

“It’s good that we can prosper again, but there’s no vaccine, there’s no cure, there’s still people dying. I’m just going to go to work, wear gloves and masks and be as clean and cautious as possible.”

Many feel likewise in the Traverse City area, one of the Midwest’s premier tourist havens. It’s revered for Lake Michigan beaches, cherry and apple orchards, vineyards and craft breweries, farm-to-table restaurants, miles of bike trails and a diverse arts and culture scene.

In this May 9, 2020 photo, customers pick up containers of vegetables, baked goods and other items at the downtown farmers’ market in Traverse City, Mich. In normal times, the market would be crowded with shoppers browsing leisurely among dozens of stalls. But because of the coronavirus pandemic, they are asked to wear masks and observe social distancing while lining up for pre-ordered bags of food. (AP Photo/John Flesher)

With only a few months of warm temperatures, summer is make-or-break season for many hotels, souvenir shops and other small businesses, generating profits that can sustain them during the long snowbound winters.

In these topsy-turvy times, however, many locals are conflicted. They yearn to make money and get outdoors. But they want to keep the virus away.

The need to survive economically without igniting a flareup is forcing people to make hard choices and adapt in previously unthinkable ways.

It’s also highlighting the big socioeconomic gaps in a region where wealthy part-time residents can be secure in spacious waterfront homes while restaurant cooks, store clerks and hotel cleaners weigh the risks of going to work versus sacrificing paychecks.

Meanwhile, people in the rural communities outside Traverse City, especially the elderly and sick, are facing new difficulties that can’t always be solved by going online. Internet and cell phone services are often spotty or nonexistent.

In this Saturday, May 16, 2020 photo, bicyclists cruise along the Boardman Lake Trail in Traverse City, Michigan on The trail is among many popular outdoor recreation spots in the area, where the tourism industry has suffered because of stay-at-home orders resulting from the coronavirus. Gov. Gretchen Whitmer is allowing restaurants and shops to reopen this weekend if they abide by social distancing requirements, but some local residents fear a crush of visitors could boost the number of cases in an area that has mostly avoided the virus. (AP Photo/John Flesher)

Traverse City is the largest of many tourist towns a four-hour drive northwest of Detroit, scattered among gently rolling farmland and hardwood forests. Although the city’s population is just 15,000, nearby townships are growing. Retirees and young entrepreneurs who can work remotely are attracted to the community’s walkable neighborhoods and varied recreation. According to a recent report, one of its zip codes has the most millennial millionaires of any in the U.S.

“The perception is that we live in this beautiful paradise where people come to get away from their troubles,” said Kerry Baughman, executive director of the Northwest Michigan Community Action Agency. “But we have challenges that aren’t always visible.”

As of mid-May, the 10 counties in Michigan’s northwestern Lower Peninsula had a combined 138 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 13 resulting deaths.

Meanwhile, the Detroit and Chicago metro areas had more than 97,000 cases and 6,700 deaths between them. Many of northern Michigan’s vacationers hail from those hot spots.

That puts leaders of up-north towns in an awkward position.

Jim Carruthers, mayor of Traverse City, said he “caught a lot of flak” in the pandemic’s early days for discouraging outsider visits.

“It’s pained me this entire time to say ‘No, please don’t come to Traverse City right now, we need to figure this out,'” he said. The updated message, he said, is “We want you to come have fun, but we want you to be wise and safe.”

Most summer events are canceled, including the National Cherry Festival, which typically draws huge crowds for its parades, air shows, orchard tours and fireworks. Interlochen Center for the Arts called off its summer music camp. Theaters and museums are closed. Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore is mostly off-limits, as are state park campgrounds.

Yet many stir-crazy vacationers may head north and enjoy whatever recreation they can, even if it’s just sunbathing along Grand Traverse Bay or hiking in the woods.

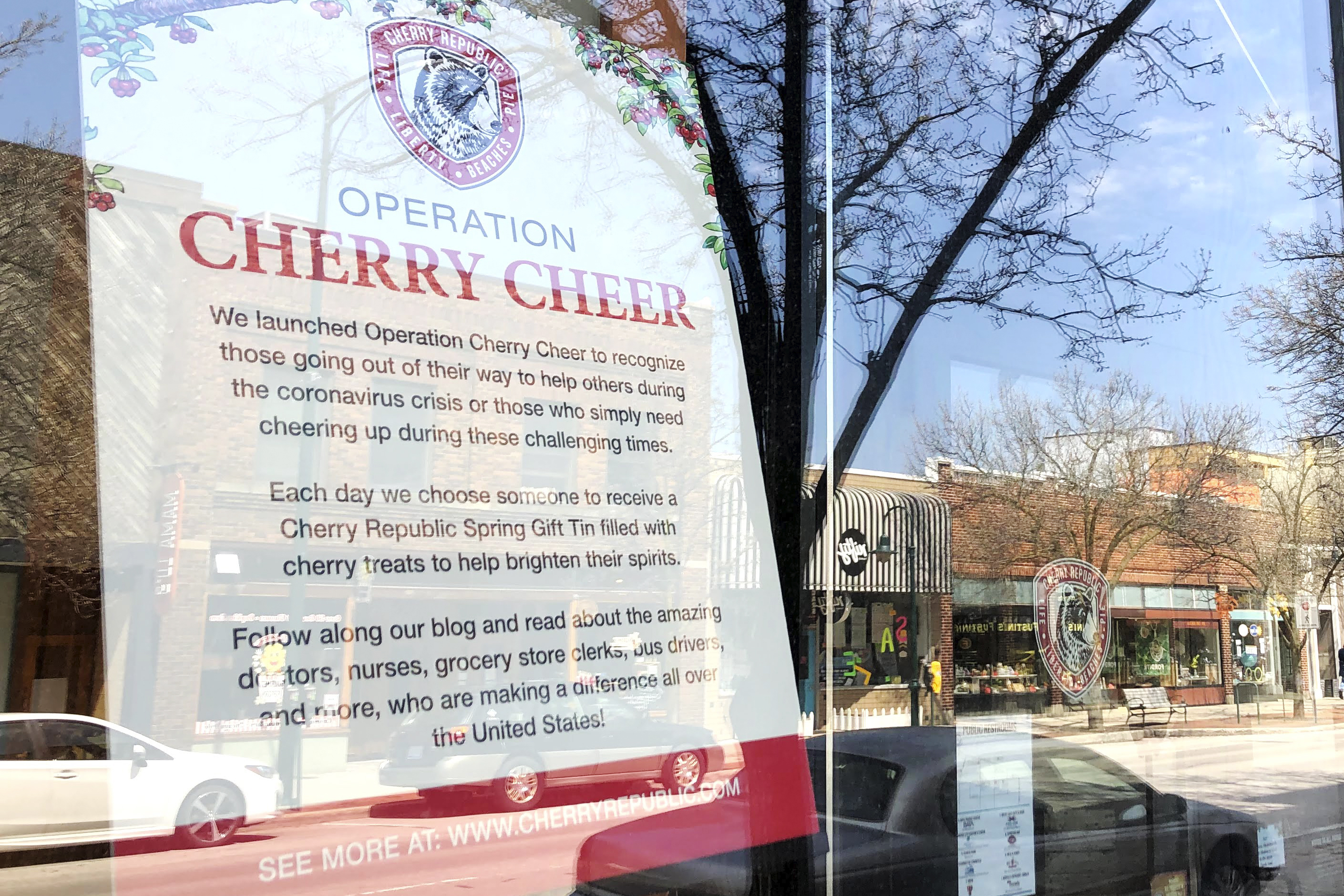

In this May 2, 2020 photo, a nearly deserted Front Street is reflected in the window of Cherry Republic, a popular downtown store that sells products made with the region’s signature fruit in Traverse City, Mich. It’s one of many local tourist-oriented businesses that have shut down during the coronavirus pandemic. With summer vacation season looming, this town on a Lake Michigan bay normally would be expecting a crush of visitors. But festivals are canceled and shops shuttered across the region, and some local residents have mixed feelings about crowds descending on the area, which might cause the number of virus cases to rise. (AP Photo/John Flesher)

“There’s so much pent-up demand, and it’s such a long-standing tradition,” said Trevor Tkatch, president of the tourism bureau.

Governments and businesses are adjusting. Customers who once browsed leisurely at the farmers’ market now place orders online, don masks and wait in line for pickup.

Sugar Beach Resort Hotel is open but, like others in the state, can offer only the bare minimum — no swimming pool or exercise room.

While some restaurants closed, others provided takeout service. The upscale Cooks’ House retooled its menu, substituting Salisbury steak and other comfort foods for its signature Great Lakes whitefish, which doesn’t travel well.

“You work twice as hard for a third of the money,” co-owner Eric Patterson said. “It’s now starting to get on the desperation side.”

To be extra careful, he’s waiting until mid-June to reopen the dining room and add outdoor seating in keeping with social distancing requirements.

The precautions so far have helped keep the area’s coronavirus numbers low, but the region’s medical resources are limited, and health officials are wary about what the partial economic reopening might bring.

“If we do this the wrong way, blow off the masks and blow off the distancing … we could start seeing a lot of cases and shut back down again,” said Dr. Christine Nefcy, chief medical officer of Munson Healthcare, which operates nine hospitals in northern Michigan.

Some considered the strict lockdown excessive.

Barbecue restaurant operator Dean Sparks doesn’t want his servers to wear masks, which he thinks would be a turnoff for customers.

“If you’re not comfortable, stay home and if you are willing to take the risk, go out,” Sparks said. “We’re all adults here and can make our own decisions.”

Catch up on Great Lakes Now’s COVID-19 coverage:

State Struggle: Budget shortfalls stall Asian carp plan, put cleanups at risk

Despite virus, Michigan groups aim to keep summer fireworks tradition

Sewage Check: Great Lakes researchers look to wastewater for data on COVID-19

Featured image: In this March 18, 2020, photo, a tongue-in-cheek message is displayed on the marquee of the State Theatre in Traverse City, Mich. (AP Photo/John Flesher)