“Was that a bear?”

We were a few hours into our drive eastward from the Winnipeg airport when the first black bear crossed the road in front of us. Chicago-based videographer Doug Clevenger twisted back and tried to wrestle his camera from its case in the back seat of the rented SUV as I (safely) spun the car around on the Trans-Canada Highway.

It wasn’t a story about bears that had brought us to the Manitoba-Ontario border, but we sure as hell weren’t going to pass up footage of one!

The bear disappeared into the woods on the south side of the highway, but I followed its route on the gravel road for a few yards. In my head, I hoped Doug was learning I was game to chase a story, even if we didn’t catch this part of it. He and I had met for the first time at baggage claim at the airport when we arrived that morning for his first assignment for Great Lakes Now.

The Experimental Lakes Area works to maintain a closed system of water so that experiments are not compromised, Photo by Sandra Svoboda

When we were interrupted by the bear – and a second one later that also eluded the camera – we were on our way to a remote area east of Kenora, Ontario, where scientists are working to better understand freshwater systems.

In this closed system of lakes, researchers can manipulate water chemistry – polluting with purpose, if you will – to see what happens in the real world over time in freshwater systems.

Their current work could better inform oil-spill cleanup, further understanding of what happens when marijuana is introduced to water systems through human waste or help answer countless other research questions the staff and visitors to the site are working on.

Getting There

The journey to the Experimental Lakes Area for me began at the International Association of Great Lakes Research conference in June, where Sumeep Bath, the communications manager for the site, spoke about his job helping scientists communicate with the larger public.

The Great Lakes Now team and Sumeep Bath, the communications manager for the International Institute for Sustainable Development’s Experimental Lakes Area poses between Winnipeg, Manitoba and the research station in western Ontario, Photo by Sandra Svoboda

He showed slides of pristine lakes that took me back to family canoe-camping trips in the Boundary Waters area of Minnesota and Ontario. He talked about the unique research environment these scientists work in, a system of separate lakes where experiments are conducted, observations recorded, hypotheses tested and results reported. He introduced the work of the International Institute for Sustainable Development, which owns the Experimental Lakes Area.

I knew Great Lakes Now had to go to bring audiences a firsthand look at research into the complexities and mysteries of freshwater systems and the people doing the work.

WATCH OUR SEGMENT: Polluting with Purpose

SHOOTING SCIENCE

Over the two full days Doug and I were there, we collected far more footage than made it into the piece that aired in Episode 1010 of Great Lakes Now. But I’ll tell you a little bit about our adventures that didn’t make it on screen.

First there was the bear. We covered that.

Then there was the rest of the drive in. Leaving the Trans-Canada Highway – which is a two-lane road where it passes by the Experimental Lakes Area – we then drove for dozens of miles on gravel road. We passed some parked cars where canoers and kayakers had stopped for some camping, and then we started seeing the signs for the lakes: numbers.

The Great Lakes Now team – videographer Doug Clevenger and Program Director Sandra Svoboda – on assignment at the Experimental Lakes Area in Ontario, Canada, Photo by Sandra Svoboda

We got footage of this with Doug balancing his camera on his shoulder while standing out of the moonroof of our rented SUV. I won’t confess at what speed he finally asked me to slow down.

When we got to the community, we lived like the researchers do in a bunkhouse with shared showers and living space. Meals are communal – think summer camp dining hall – but tasty! Conversations ranged from the scientific to the personal as the remoteness of the site and shared nature of the research build bonds.

During our stay we shared guest privileges with a performance art group from Winnipeg: Walk and Talk Theatre Company. The Experimental Lakes Area started a visiting artist’s program this year, and Walk and Talk was part of it.

The three troupe members spent a week at ELA – we gave them a behind-the-scenes look at TV production as they tagged along with us. We even made them hold light reflectors at one point…

Great Lakes Now interviews Lauren Timlik, in the boat, who is a researcher at the Experimental Lakes Area in western Ontario.

But on their own time, they composed, sang, sketched, wrote and gathered inspiration from the setting.

“Often when we have started a creation process, we’ve tried to find periods of time to escape or just get outside of the city and focus. And I think we all take inspiration from the natural world,” said Tanner Manson, who works as the group’s producer, production manager and movement director. “It’s so important to get outside of your bubble, your box and see what else is out there.”

BACK TO THE SCIENCE

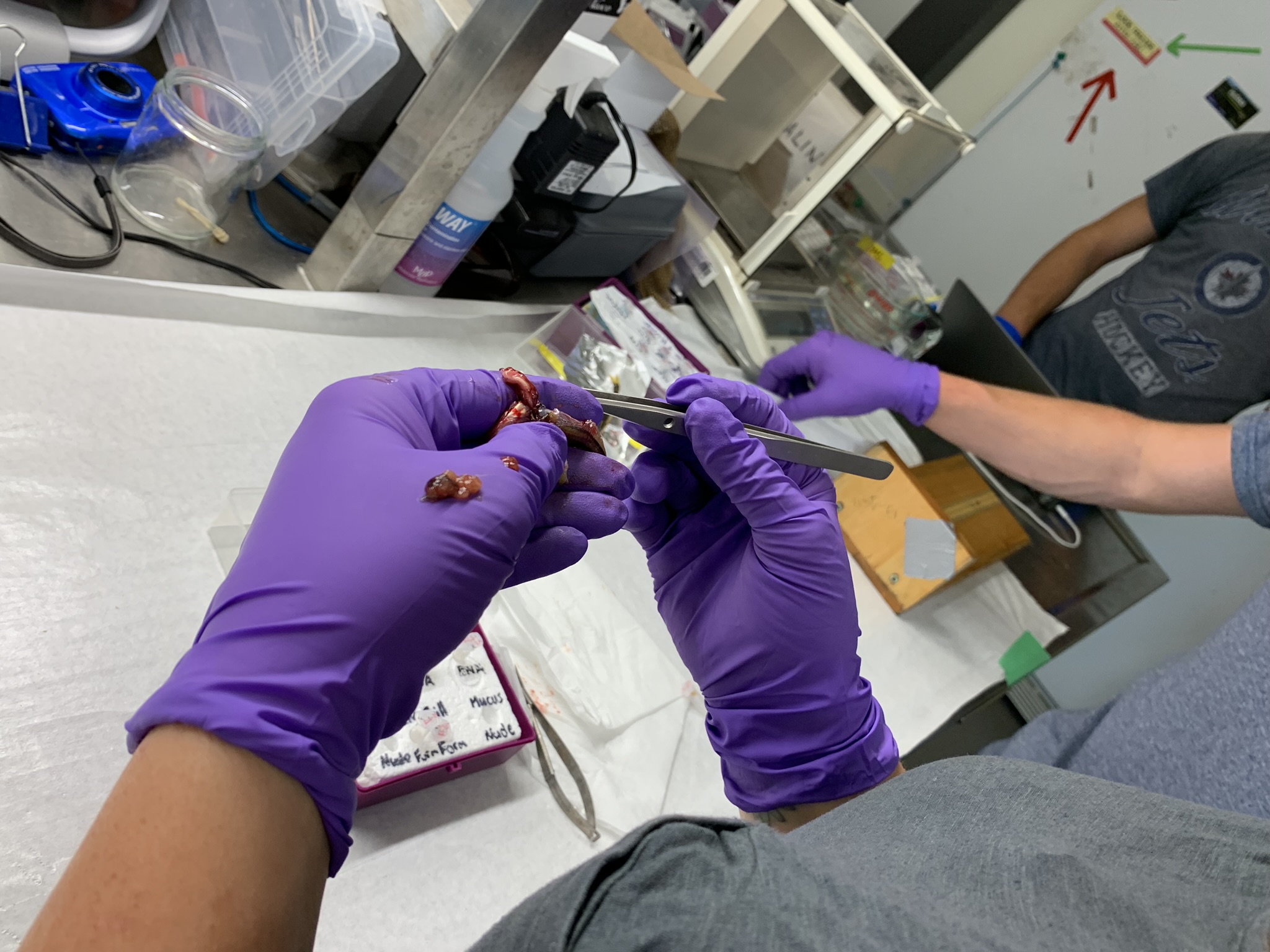

We also spent hours with scientists, who generously explained their work, demonstrated their procedures and reflected on the intersection of science and policy, which isn’t far from whatever they’re doing here.

Lauren Timlick, a graduate student and field biologist at the Experimental Lakes Area, considered the Kalamazoo River spill in western Michigan when she designed her current work researching the impacts of oil spills on freshwater systems.

“It is a balance to cut because as scientists, you always want to not expect a result. You have to go into something (thinking) ‘I could see a crazy result that could get me published and in Science or Nature, but I could also see nothing,” she said. “Both are very important results, especially when it comes to contaminants and pollutants.”

While there, we also learned about other experiments taking place. For example, a water diversion between the lakes means one of them is now warming – perhaps faster than it would have on its own.

Here the ELA researchers have spent a decade learning what impact climate change – specifically warmer waters in these lakes – mean to fish populations and other critters that live here.

“We really treat our lakes like test tubes. It sounds a little bit crass, but I think it’s a useful way to think about it,” said Pauline Gerrard, the deputy director of the Experimental Lakes Area. “The difference between the research that we do here is that we do stop whatever chemical addition we’re doing and we’re able to completely stop that chemical add.”

Great Lakes Now Program Director Sandra Svoboda, left, at the Experimental Lakes Area in western Ontario.

THE IMPACT

Like in the media business, it’s a bit difficult to judge the true impact of the work happening here.

If you do a search on Google Scholar, a database of academic articles, for “Experimental Lakes Area and Ontario”, you’ll get nearly 7,000 results – a few hundred just from the last few years. It’s a busy place where scientists gather data for their peer-reviewed publications.

Fish dissections are part of the work at the International Institute for Sustainable Development’s Experimental Lakes Area labs, Photo by Sandra Svoboda.

IISD has offices in New York and Ottawa, the capital of Canada, and program officers aren’t shy about sharing their work with politicians and policymakers, we were told. The scientists, researchers and graduate students also report their findings at numerous conferences.

Personally, I’d love to head back to ELA – so if you’ve got questions or another story idea, send it my way, please: Ssvoboda@dptv.org or @DetSandra on Twitter.

And maybe on the next trip we’ll get those bears on camera for you!

Program Director Sandra Svoboda took a moment to relax at the International Institute for Sustainable Development’s Experimental Lakes Area. But just a moment, Photo by Doug Clevenger

Featured Image: Researchers at the International Institute for Sustainable Development’s Experimental Lakes Area work on a series of inland lakes doing research about the impacts of pollution on ecosystems and water quality, Photo by Sandra Svoboda