The Great Lakes’ history of fishing can be separated into three general periods beginning with Indigenous nations’ utilization of the lakes for their subsistence.

That was followed by the commercialized harvesting of fish on massive scales, and then the current state of the lakes’ fisheries: modest commercial utilization combined with extensive recreational angling.

“It’s doing good now,” said Cory Goldsworthy, Lake Superior area supervisor for the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, referring to fish populations in the lakes. “We recognized back in 1888 that overfishing was having an impact, even back then, primarily on whitefish.”

He described that as a turning point in the lake’s management.

“That was the first year a federal fish hatchery was built on Lake Superior, for purposes of stocking whitefish. But throughout time they also stocked a number of other species,” Goldsworthy explained. “In 1917 Minnesota opened up a hatchery on Superior. It’s actually the building I’m sitting in now.”

Goldsworthy said Minnesota raised and stocked lake trout in Superior in an effort to replenish stocks.

“As we go through time there are essentially no real commercial restrictions or regulations all the way up until the mid-1960s,” he said. “So we started off with around 400 or so commercial operations, no limit on the fish they can catch, the whole works.”

The start

Long before Europeans laid eyes on the Great Lakes, Indigenous tribes had mastered its abundant fisheries. Archaeological evidence offers evidence of robust fishing communities on the lakes as early as 3,000 to 2,000 B.C.

Explorers, fur traders and missionaries wrote about Great Lakes fish and fishermen, and stories of Lake Huron’s bountiful fishery date to as early as 1623. French missionary Gabriel Sagard wrote about both abundance and size of fish during his early 17th century travels:

For indeed in this Fresh-water Sea there are sturgeon, Assihendos (whitefish), trout, and pike of such monstrous size that nowhere else are they to be found bigger, and it is the same with many other species of this that are unknown to us here (in France).

Chippewa Village, Sault Sainte Marie, Michigan, 1850, Photo by State Archives of Michigan

Members of more than a dozen tribes including Chippewa, Ottawa, Fox, Menominee, Mascoutin, Potawatami and others pulled fish from the lakes and its nearby tributaries.

Tribes fishing the lakes fashioned gill nets with basswood and nettle. They cast the nets from canoes, side-by-side suspending nets between the canoes, and would pull fish from the water with ease.

Night fishing was a popular endeavor also since fish were drawn to light sources.

Using pine resin and charcoal to fashion torches, Native peoples attracted fish with the flame then speared them. This was especially effective on lakes Huron and Michigan for species like walleye and sturgeon.

C.M. Davis’ “Readings in the Geography of Michigan” describes the region’s residents like this:

In the 1700’s travelers might have found Algonquins pitching their bark lodges along the beach at Mackinac, spearing fish among the rapids of St. Mary’s River, or skimming the waves of Lake Superior in their canoes.

Caught by the hundreds of thousands

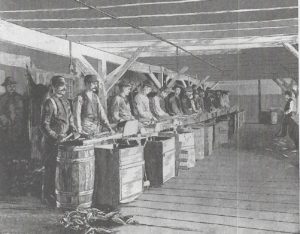

Interior of a fish-packing plant showing a fish-cleaning gang at work in Sandusky, Ohio, Photo by U.S. Commission of Fish and Fisheries

But by the very early nineteenth century, with a swelling tide of Europeans, settlers got into the fishing game too. Newcomers on the lakes were filling barrels with pickled and salted fish they’d seined, speared and hooked, then distributed mostly for family and community consumption. And whitefish were plentiful beyond imagination.

In “The Good Years: A History of the Commercial Fishing Industry on Lake Erie,” Frank Prothero finds a lake flush with fish:

American navy men laboring on the construction of (Commodore) Perry’s ships at Presque Ile in the summer of 1813 sent home accounts of whitefish, so plentiful that one might fill a net by simply casting it into the water from the beach.

Edward Guillet in “Early life in Upper Canada” stated that “in some parts of Lake Erie Single hauls of 90,000 whitefish were not unusual” and in the Detroit River fish were driven into pens by the hundreds of thousands to be later dried and used as fertilizer.

Fish become big business

As fishing the Great Lakes became a major business, the commercial apparatus that would see great successes, and failures, was born. Fleets of gill-net boats, including steam-powered vessels, worked ever-greater distances from home ports, farther from land and utilizing longer nets at greater depths. Manual net lifters gave way to powered lifters and harvest numbers climbed. The pattern of maximum harvest continued well into the 1900s.

While the ingenuity fed tens of millions during the next 150 years, it nearly wiped out the fish. Some species disappeared, like the blue pike.

According to the Ohio Biological Survey, between 1950 and 1957 blue pike harvests in lakes Erie and Ontario ranged between 2 million and 26 million pounds. By 1959 just 79,000 pounds were reported. In 1964 the number was less than 200 pounds. The blue pike is now just memory – and a specimen in a jar in a laboratory.

By the 1850s massive nets had evolved and were utilized by companies operating steam-powered vessels, which grew larger and larger as investment poured in and profits were made. Continued mechanization meant smaller fishermen, including Indigenous groups, could no longer compete with bank-financed operations set up by European immigrants. Many Indigenous fishermen were relegated to working in the employ of commercial operations. The few that remained independent operated small, mostly family organizations which pulled enough fish from the lakes to feed kin, with little surplus to sell at markets.

The arrival of railways and cold storage meant fish could be caught and shipped fresh, on ice, just about anywhere. The opportunity for large-scale profits drove the industry.

For the Great Lakes fisheries, that was when everything went downhill.

Targeted fish populations in constant fluctuation

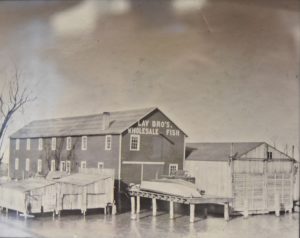

The Lay Brothers Wholesale Fish Company, Port Clinton, Ohio. Photo by the Ottawa County Museum

Currently, scientists say that while Lake Erie possesses about 2 percent of the water in the Great Lakes, it’s home to about 50 percent of the fish. It’s hard to imagine it was any different in the past – and likely a reason why its waters were so heavily pressed by those seeking fish and seeking to keep others out.

In “The Good Years, A History of the Commercial Fishing Industry on Lake Erie,” Frank Prothero writes that Canadians were not happy with their fishing friends from the south.

American catches continued to grow larger…Much of their catch was procured in Canadian waters and the simple expedient of placing patrol boats on the Canadian side was shortly going to curtail their lucrative poaching activities.

The desire to exclusively control the Great Lakes’ fisheries resource was a recurring theme in history, as well as the desire to protect it.

Industrial Revolution advanced society, harmed lakes

By the mid-19th century, commercial fishing was booming and so was industry, as towns and cities grew. But the rising populations of the lake states and Ontario, combined with serious pressure by thousands of commercial fishing operations, hit the fish populations hard.

The major urban areas of Toronto, Hamilton, Buffalo, Cleveland, Toledo, Rochester, Detroit, Chicago, Duluth, Superior and Milwaukee grew exponentially between 1850 and 1900.

Population in these 11 cities swelled from a combined 215,000 to 3.64 million in 50 years. The growth gave rise to great numbers of foundries, smelters, mills, oil fields, chemical factories and all manner of industry.

In Ontario’s Oil City there were 27 refineries operating by 1860. In Ohio’s Wood County near Toledo, 25 years later, oil fields opened that would eventually see 5,500 operating wells. Sewage from cities and intense timber and agriculture activities also took their toll on the lakes. All the while commercial operations pressed forward for maximum catches of lake trout, herring, whitefish and lake sturgeon.

Fishermen on the lakes began to notice declines in their catches, attributing it often to pollution from the thousands of new factories and the growing cities.

But the introduction of non-native species was a concern, as well. That included alewives that competed for food, common carp that uprooted vegetation and sea lamprey that fed off larger fish. Each took its own toll on native commercial fish.

Market glut, lower prices push fishermen to increase catch

In the years following the Civil War, the competitive nature of the industry saw a rise in the lakes’ yields. This in turn pushed prices for catches down. The 1880s were especially fraught with troubles for the industry as fishing fleets worked harder to earn income by harvesting more fish at lower prices.

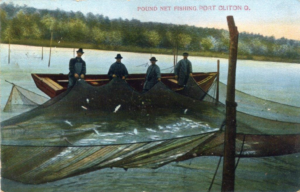

Pound net fishing, Port Clinton, Ohio. Photo by the Ottawa County Museum.

During the past two centuries, most populations of commercially exploited fish have either completely or partially collapsed at one time or another. Atlantic salmon disappeared from Lake Ontario, lake trout from lakes Michigan, Erie and Ontario, and blue pike from lakes Erie and Ontario. A handful of deepwater chubs, also called ciscoes, have either been extirpated from individual lakes or the entire Great Lakes system. Two of the nine cisco species present in the lakes in 1929, the deepwater and the shortnose, are now considered extinct.

In the two decades prior to 1900, many of the commercial species being taken plummeted. Lake whitefish production in the lakes declined from about 24 million pounds annually to nine million. Lake sturgeon dropped from about eight million pounds to less than two million. As these stocks declined, fishermen turned to other species to pursue profits. During that 20-year period, total commercial production on the Great Lakes rose from about 80 million pounds of fish to about 146 million. Desirable whitefish, sturgeon, herring and lake trout populations declined as catches of other fish rose.

The revolving door of once-popular commercial fish species have included northern pike, walleye, pickerel, American eel, burbot, trout, freshwater drum, yellow perch, suckers, catfish, muskellunge, grass pike, mullet, white bass, white perch, smelt, sauger and bowfin, among others.

Lake managers take note

The free-for-all commercial fishing game could not last. Goldsworthy said that, over the decades, the intentions of fisheries managers in Minnesota and elsewhere was to do the right thing, it simply wasn’t working.

“Throughout time there had been attempts for different jurisdictions like Minnesota, Wisconsin, Ontario, Michigan, for everyone to get on the same page and have the same regulations, but we could never figure out how to do that. Everyone had their own commercial operators that each did their own thing,” he said. “No one really wanted to coalesce around one regulation.”

According to the Great Lakes Fishery Commission, between the late 1800s and the 1950s, the U.S. and Ontario tried no less than 40 times to create a system of cooperation to manage the lakes, including two signed treaties which never materialized into actionable plans.

In 1954 a treaty between the U.S. and Canada resulted in the formation of the Great Lakes Fishery Commission, a joint body which now facilitates the collaborative management efforts of Ontario, the lake states, Native American tribes and Canadian First Nations. The GLFC and its stakeholders have been working together since its inception on all things Great Lakes fish, including battling invasive species such as the lamprey; determining which fish should be caught, how many and where; and other science-based approaches to lake issues.

Featured Image: Aboard one of the Bell Fish Company boats, Photo by the Ottawa County Museum

Read the second part of this series, on successes and conflicts in the modern era of the fishing industry in the Great Lakes, here: