The Great Lakes region’s ongoing quest for a new icebreaker was renewed in July when the Senate Commerce Committee included the vessel in its Coast Guard reauthorization legislation for 2020.

Icebreakers are a special class of ship designed to break through ice cover and clear a path for other ships.

In announcing the legislation’s approval, Wisconsin Sen. Tammy Baldwin made the business case for the new icebreaker.

“Inadequate icebreaking on the Great Lakes this past winter cost the U.S. economy over $1 billion and over 5,000 jobs,” Baldwin said, citing data from the Lake Carriers’ Association, a Great Lakes shipping industry group.

The billion dollar revenue loss does not include $171 million in lost tax revenue by federal, state and local governments, according to Baldwin.

“The U.S. Coast Guard was down four icebreakers for a significant period of time this past winter,” according to Mark Pietrocarlo, the Lake Carriers’ Association’s board chair.

“One icebreaker took 17 months to repair, one was on the East Coast for a major overhaul and two others missed more than a month of icebreaking,” Pietrocarlo said.

Steel manufacturer ArcelorMittal also called for a new Great Lakes icebreaker in a 2017 infrastructure report, saying that its Cleveland operation is “100 percent reliant” on maritime shipping for raw materials.

In addition to a new icebreaker, the report called for funding to maintain the existing fleet.

It is unclear where the Coast Guard stands on manufacture of a new icebreaker for the Great Lakes.

“In general, the Coast Guard welcomes additional resources but doesn’t comment on pending legislation,” said Lorne Thomas, government affairs officer in Cleveland’s Great Lakes region office.

Thomas said in recent years the Coast Guard’s focus has been on polar icebreakers that are designed for open waters and have reinforced hulls. They are increasingly seen as important to national security interests at the poles.

He declined to comment on the cost or a construction timeline for a new Great Lakes icebreaker and said a U.S. and Canadian agreement provides for support of each other’s operations during the peak icebreaking season.

The current congressional authorization of a new Great Lakes icebreaker follows a similar 2015 approval championed by Michigan Sen. Gary Peters that Congress ultimately failed to fund.

Peters made a business case similar to that of Sen. Baldwin, putting a spotlight on decreased cargo tonnage, lost revenue to business and lost jobs.

“This new heavy icebreaker is a much-needed addition to the Coast Guard’s Great Lakes fleet, and will help ensure that Michigan businesses can continue to rely on shipping to move their goods year round,” Peters said in 2016.

Federal funding fatigue

The tab in 2016 for a Great Lakes icebreaker was estimated to be $200 million.

In the Great Lakes region in 2018, a new Soo Lock received congressional and presidential approval and $75 million of an estimated cost of $922 million has been approved.

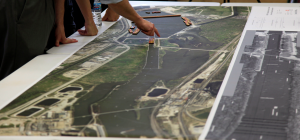

The region is also looking for up to $778 million for modifications to the Brandon Road Lock in Illinois, a location the Army Corps of Engineers has identified as a chokepoint to stop the Asian carp advance.

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Chicago District Brandon Road Lock Briefing, Photo by Patrick Bray, U.S.A.C.E. via flickr.com cc 1.0

Since 2010, approaching $3 billion has been sent to the region for Great Lakes restoration with anticipation that $300 million or more annually will continue for the foreseeable future.

In the wake of current projects, the new icebreaker may receive tougher scrutiny from congress when it allocates money for 2020.

Lake Carriers’ Association’s President James Weakley doesn’t see funding fatigue in play because a new icebreaker is a “legitimate” project, he said.

“There can be national implications when steel made in the Great Lakes region isn’t able to keep up with demand,” Weakley said. He cited Texas, where 865,000 people depend on Great Lakes region steel mills, according to the Department of Homeland Security study “The Perils of Efficiency”.

Former International Joint Commission policy adviser Dave Dempsey has observed U.S. and Canadian, and federal and state budget negotiations since the 1980s and is cognizant of funding fatigue.

“The region has gotten much better at capturing money for the Great Lakes, after years of sending far more tax money to Washington than it received back,” Dempsey said.

But he emphasized that “it’s important for out-of-region congressional appropriators to understand that funds for a new icebreaker and Soo Lock are for transportation projects, not for environmental issues.”

The Coast Guard currently operates nine icebreakers in the Great Lakes with most of those commissioned in the 1970s. Of the nine, only the Mackinaw, commissioned in 2006, is considered a heavy-duty icebreaker.

Sen. Baldwin’s office did not return a call requesting comment.

The approval for the new icebreaker must still be passed by the full senate.

Featured Image: Stewart J. Cort in Lakes Superior ice, Photo by Lake Carriers Association