Increased flooding, human impact being blamed

In 2012, a two-day thunderstorm dumped between five and 10 inches of rain on Duluth and along many areas along the coast of Lake Superior. Already saturated with water from previous rainstorms, the area was primed for historic flooding. The immediate after-effect of the event came in the form of submerged soccer fields, broken pavement and mangled streams and creeks that are still being restored today.

A few weeks after the event, the Apostle Islands on the northern tip of Wisconsin experienced its first wide scale blue-green algal bloom. Since then, as heavy rainfall events have swept through the area, a blue-green bloom event has followed.

Scientists looking into the emergence of blue-green algal bloom events in Lake Superior have reason to believe they will continue.

“We are certainly seeing more cases of blue-green algal blooms,” said Brenda Moraska Lafrancois, a Midwest-region aquatic ecologist working for the National Park Service. “There really isn’t a history of blue green algal blooms in Lake Superior.”

Despite the destruction wrought by the 2012 flood event, Moraska Lafrancois said the worst algal bloom event swept through the Northland last June.

“The 2018 event was probably the largest and most notable in its extent and severity,” she said, “but we don’t really have an indication of whether the next bloom will be bigger.”

Despite their increasing prevalence, there’s still a lot of uncertainty about the blue-green algal blooms. In-depth research into their connection to Lake Superior has ramped up only after recent events.

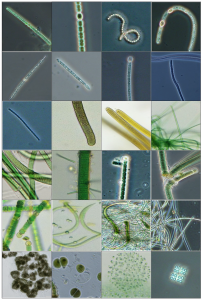

The organism in blue green algae is called cyanobacteria and it’s been around a long time. Kait Reinl, a graduate student at the University of Minnesota-Duluth who studies cyanobacteria, said this particular species of algae has a “competitive advantage” over its phytoplankton cousins because of how it has evolved.

“A lot of the different types of cyanobacteria have the ability to move up and down in the water to capture nutrients,” said Reinl. “So some algae just float and are at the mercy of the water. Cyanobacteria have gas vacuoles to change their buoyancy.”

Typically, algae growth is limited by the amount of phosphorus and nitrogen in the water. But with major flood events and the human impact on the watershed, more of these nutrients find their way into the water, which eases the burden on finding food.

To compound their advantage, Reinl has found cyanobacteria’s optimum growth is in warmer water temperatures. Lake Superior, no stranger to warming waters, is heating up faster than the global average of lakes.

“Basically, these organisms have hit the evolutionary jackpot,” Reinl said.

While incidents like the 2018 flood are proof blue-green algae are cashing in on that jackpot, it’s not just their increasing prevalence that has officials concerned. Cyanobacteria is known to release toxins as well. Harmful to the liver and brain, there have been reported cases of pets dying due to exposure.

Like the triggers that have caused these bloom events, what causes toxins to be released is also a mystery to officials.

“It’s hard to keep up with how this problem is changing,” Reinl said. “It’s multi-faceted. You don’t always have to have a bloom to have toxins, you don’t always have to have toxins when you have a bloom. We don’t understand fully yet how all these things are connected.”

In response to the growing issue, Reinl and her team tested three sites in the summer of 2017, using a variety of temperatures and nutrient ratios. They found cyanobacteria flourished in high temperatures and low nutrient ratios.

Then this last summer, they picked samples from 26 different ponds, rivers and lakes and grew them under the best conditions from their previous experiment. The intention was to further understand what similarities between those sites were promoting high algal growth.

“It’s relatively unexplored because Lake Superior, while it’s experiencing algal blooms, it’s nothing like on the scale of Lake Erie or some of the things being seen in Saginaw Bay,” said Reinl.

Lafrancois said people have been comforted by the idea that Lake Superior is in better shape than other Great Lakes and so the concerns of blooms happening south of Duluth haven’t migrated north. “People often think with limited development, it’s less vulnerable to these kinds of stressors.”

Lafrancois did cite one parallel between Lake Erie’s history with blooms and Superior’s more recent experiences — nitrogen and phosphorus usually made its way to each lake by way of tributary.

However, both Lafrancois and Reinl have cautioned using Lake Erie and Saginaw Bay as roadmaps for how to deal with Superior’s algal blooms. Lake Superior’s nutrients can’t be attributed to agriculture and industry, and its nutrient surges aren’t as intense as those in other lakes.

“We can’t even use other Laurentian Great Lakes as a model for here, because it’s a completely different lake,” said Reinl, “It’s a completely different landscape. It’s a different kind of cyanobacteria.”

Featured Image: Bloom of cyanobacteria, Photo by Lamiot via wikimedia cc 3.0

1 Comment

-

Does the green algae mean no more licking rocks to see if they contain agate?