The only floating zipcode in the U.S.

(Editor’s Note: Glen Mannisto is primarily an art journalist contributing to numerous local and national art publications, art galleries and museums, including Detroit’s Metro Times, and currently writing for the Detroit Art Review.com. He taught the History of Modern Design at the College for Creative Studies for many years and often explores the use of language in experimental writing.)

The Detroit Ambassador Bridge’s graceful arc over the blue water of the Detroit River conceals in its shadows three workboats. Each boat plays an essential role in the everyday life of the river and all three go mostly unnoticed in their daily routine. They are moored, stern to bow, in a row, close together, each in its own way, ready: the Detroit Fire Department’s 75 foot, Curtis Randolph fireboat; the Lake Pilot Association’s 50’ Huron Belle; and the 48’ J.W. Westcott ll mailboat, the only floating zip code (48222) in the United States

Approaching the Westcott’s dock and dispatch office on the Detroit river front, Photo by Robert Hensleigh via Glen Mannisto

The Curtis Randolph was named after a young African-American Detroit fireman who, in 1977, lost his life in the line of duty. It was commissioned in 1979 by Mayor Coleman A. Young to replace the obsolete John Kendall. The Curtis Randolph is the only class A fire boat between Chicago and Cleveland. Fortunately, the Curtis Randolph is not used often but sits vigilantly, awaiting use as when, in 2016, it was loaned to the city of St. Clair, Michigan, and raced sixty miles to fight a fire at the St. Clair power plant, as well as, recently, to fight the fire on the old BobLo boat. It is best known for displaying its powerful pumping prowess at the Detroit Fireworks, spraying great streams from its four monitors.

Moored near the Randolph is the Huron Belle which has the risky and strangely archaic task of shuttling pilots to foreign vessels– ships flying foreign flags from all over the world– that deliver and pick up cargo at Great Lakes ports. Foreign vessels must be piloted by a licensed pilot who is familiar with local navigation. It is an awesome, somewhat frightening process to watch a pilot climbing the vertical sides of salties (foreign ships) on Jacob’s ladder in order to assume control.

Former Captain of J.W.Westcott ll and writer Glen Mannisto and Deckhand Disdpatcher Kelly Quinn, Photo by Robert Hensleigh via Glen Mannisto

The most active of the workboats – and the one with what many say is the most romantic job – is the J.W. Westcott ll. For twenty-four hours a day of the nine-month long shipping season, the Westcott “mailboat” delivers mail, cargo, and crew members to mostly bulk freighters that come through the straits of Detroit (Detroit is French for straits). In 1900, there were approximately 2000 freighters active on the Great Lakes. By the mid 50’s, as freighters got bigger and more able to carry larger tonnage, that number had dwindled to 300 bulk freighters carrying iron ore, coal, limestone, salt, cement, and grain from mines and farms to steel mills and factories in the industrial cities like Detroit, Cleveland, and Chicago.

“The Westcott began carrying the all-important ‘mail-in-a-pail’in 1895”

Of course, the auto industry had stimulated much of the river’s shipping commerce but even before the advent of that, in 1874, John Ward Westcott had started rowing a small boat out to passing ships which were carrying timber, grain, and coal to deliver supplies via rope and bucket.

J.W. Westcott mailboat headed out for mail delivery and crew exchange to the American Mariner, Photo by Robert Hensleigh via Glen Mannisto

The Westcott began carrying the all-important “mail-in-a-pail” in 1895 and was for many years the only form of communication between shipping companies and their boats, and between sailors and their loved ones. It was a way of getting “hard copy” of telegraph messages of orders for destination to the captains of vessels and to get affirmations of love from lover to sailor (or at least vice versa.)

Life on the Westcott is addicting. After graduating from college, and after discontentment with developing film in a commercial darkroom and a bout of profound copy writing boredom, I took what was meant to be a summer job at the Westcott.

I stayed nine years and sometimes wish I’d never left. Bill Redding, the current dispatcher and boat operator who joined the Westcott family just after I left to teach, has been with the company for more than thirty years. Paul Jagenow, a now-retired longtime dispatcher, Detroit River’s secret historian and voice of the Detroit River shipping industry, was there for more than 40 years. Sam Buchanan, general manager and ship master, who, after graduating from high school, rode his bike over from his house in the neighborhood behind the Westcott office and asked if there was job for him there, has been with the Westcott now for some 34 years and counting. His two sons and daughter now work beside him.

“Your body becomes a gyroscope in the rollicking waves”

The job requires complete attention. Your body becomes a gyroscope in the rollicking waves in order to remain somewhat vertical to perform the simple task of putting a bundle of mail in a pail. In the 1970s, when I was manning the Westcott’s helm, we averaged about 20 boats per 8 eight-hour shift, but that number could climb to as many as 60 per shift. There were times that we were barely able to get to and from the dock to get mail and freight and sometimes had to signal the freighter to slow down (three quick blasts of our horn) if “she had a bone in her teeth” (going so fast she had white bow waves like a joyful running dog with a white bone in its mouth) to catch them – or they went without their coveted mail.

J.W. Wesctott ll’s deckhand Brian Heikkuri aiding pilot in pilot exchange on the Cypriot ship Isolda, Photo by Robert Hensleigh via Glen Mannisto

If we were carrying crew members to a freighter and they had to make the tediously dangerous climb up the Jacob’s ladder to board, we sometimes ended up out in Lake St. Clair or down river by the time we completed our mission. With a little wind coming up-river it was often exhilarating and exciting work, but with a lot of wind coming up-river , the old sou’wester, it was creepy-treacherous, especially at night, with limited visibility.

From my first day as a deckhand when I was sitting in front of the dispatch office with seasoned sailor, Captain Richard Eathorne, nervously awaiting a freighter for mail delivery, it seemed every day brought a new adventure. As when I was sure I saw a body fall from the Ambassador Bridge and a little while later we were pulling a half-naked (the impact of the water had torn his clothes off) disgruntled man from the river who, in a dazed rant, was screaming “Oh my God I can’t even kill myself right!” Or when, securing a Jacobs ladder for a pilot a few days later to board a saltwater ship from Monrovia, Liberia, from the West Coast of Africa, I looked up to see three dreadlocked Rastafarians greeting me with beautiful smiling faces.

“It wasn’t just water but the world that flowed through Detroit”

I learned quickly by watching the river from the dock of the Westcott that it wasn’t just water but the world that flowed through Detroit. It seems the Westcott is connected to this global lifeline of vitality that, like the powerful Detroit River itself, is always moving, revealing something new and fundamental every day – whether it is iron ore from the Masabi Range hauled to U.S. Steel mills in Detroit to make cars, or grain from Western Canada for making great pasta and bread – it’s going through this vein of Detroit.

Mail boat deliveries on the Detroit River aboard the J.W. Westcott II, Photo by BoatNerd via youtube

Once after a pilot change on a Russian ship, a well-known, comical, but perhaps paranoid pilot said, “You gotta watch them Russian captains, they’re spies, always taking notes! That Ruski captain just asked me what that big factory is in Wyandotte (a huge chemical producing plant), I told him it was our chief toilet paper factory. He asked about the big one (Ford Rouge Plant) I told him it was our main waste management facility.”

While the activity on the river is always brilliantly uncertain with an uncanny mixture of wait and run, calm and stress, there were two very painful moments in Westcott history that will never be forgotten. On October 23, 2007 during a pilot change for the Norwegian tanker Knutsen, the Westcott inexplicably took on water, overturned and sank. The captain, Catherine Nasiatka, 48, and deckhand, Dave Lewis, 50, were both killed. The two pilots miraculously dove out of the cabin and swam safely to shore. It was the only loss of life in the Westcott’s history of sometimes risky sailing, and as everyone said, it was the saddest day of Westcott history.

The sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald during the “Gales of November” on November 10, 1975 was another moment that every Great Lakes sailor was grieved by, but especially the crew of the Westcott who had serviced and enjoyed camaraderie with the crew of the Fitz for many years. Many of us who worked that shift will never forget the anxiety-filled radio communications during the night following the storm when the Fitzgerald disappeared from radar.

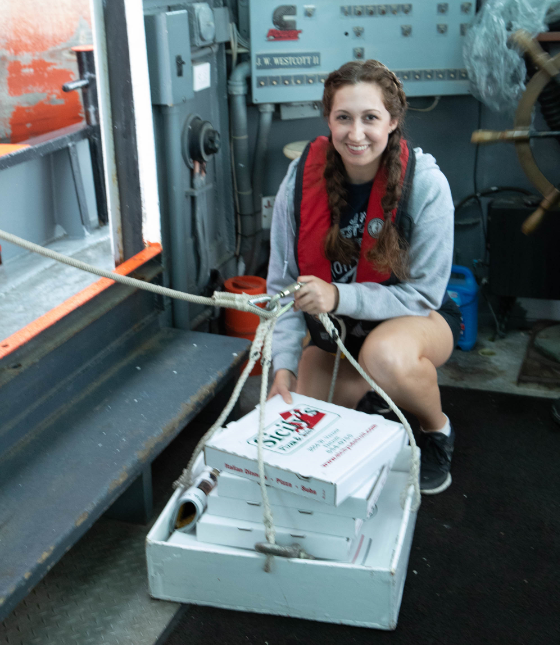

Deckhand & dispatcher Jessica Chuba prepares pizza delivery, Photo by Robert Hensleigh via Glen Mannisto

The Westcott family endowed the mail boat with a heritage that current owner and Westcott heir, James Hogan, is both proud of and somehow almost apologetic. It has not made a fortune for him or his employees, like some of the corporations it services. And while it is seasonal work and doesn’t demand a huge educational portfolio, the richness of life it provides has kept all of us loyal to its vital heritage. From the priceless parcel of land it occupies on a dock on the Detroit River, one can watch the coming and going of local river life as well as global commerce, and achieve a little global consciousness at the same time.

Featured Image: J.W. Westcott ll making crew exchange and mail delivery to the American Mariner, Photo by Robert Hensleigh via Glen Mannisto

2 Comments

-

Another interesting bit of Detroit spanning a long arc of time and into the future – unknown to most Detroit and area residents, under-appreciated by our state and our country. Other amazing examples are: Fort Wayne, our salt mines, the city’s French beginings, and on and on.

-

Great article, thanks for sharing Glen!