This article is the first in a series called The Great Lakes Promise: Cost, Resilience and Refuge. This series was made possible in partnership between Great Lakes Now and Planet Detroit.

Bird flu has hit the Great Lakes region hard this winter, killing nearly 5 million birds — including laying hens, ducks and other fowl — in Ohio and Indiana in the past two months. The outbreak is straining farmers and raising concerns about a possible risk to humans.

Since 2022, H5 bird flu (a form of highly pathogenic avian influenza, or HPAI) has devastated poultry flocks across the nation, killing over 166 million birds nationwide and causing more than $1.4 billion in losses. The virus has killed livestock and wild animals on every continent except Australia. In 2024, H5 moved into U.S. dairy cattle, placing further stress on farms and consumers and opening a new pathway for transmission to humans.

The U.S. has seen 70 human cases of H5 since April 2024 and one death. Most cases affected agricultural workers working directly with animals, but some experts fear the virus could mutate to allow person-to-person spread and touch off a human pandemic.

Researchers say vaccinating poultry is crucial for reining in H5 and reducing the stress on farmers and consumers hit by high egg prices. Vaccination could also help reduce the number of infections and the threat of a pandemic.

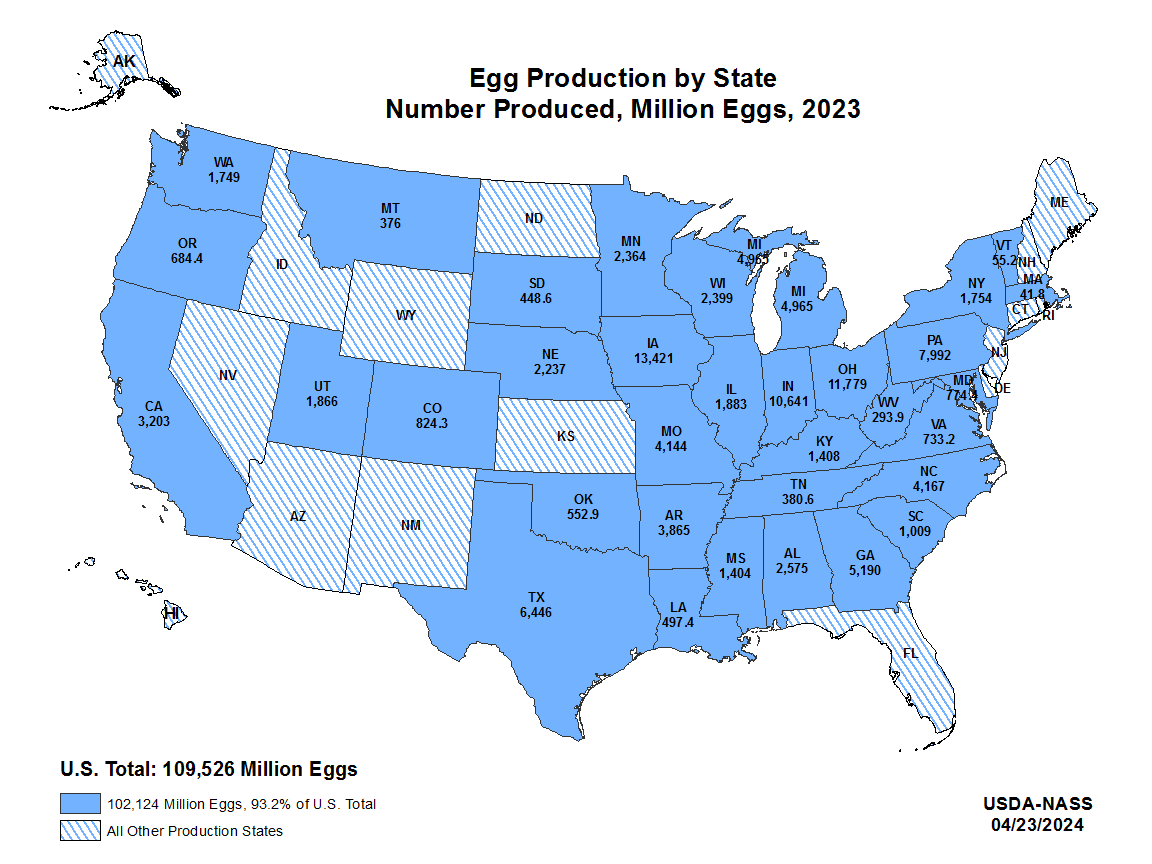

This is especially important in Minnesota, Indiana, Ohio and Michigan, where dairies, egg farms, and turkey operations have seen H5 outbreaks. Indiana and Ohio, two of the biggest states for egg production, generated 10.6 billion and 11.8 billion eggs in 2023, respectively.

The federal response is scattered. The U.S. Department of Agriculture hasn’t signaled that large-scale vaccination of laying hens is forthcoming. However, it announced investments of $100 million in researching biosecurity, outbreak response, therapeutics and vaccine candidates on March 20. The Trump administration previously laid off and then sought to rehire USDA employees working on the H5 response.

A USDA spokesperson told Planet Detroit that veterinarians, animal health technicians, and emergency response personnel involved in HPAI response have been exempted from “the recent personnel actions.” USDA workers involved in HPAI research who were terminated have been reinstated, the spokesperson said.

Carol Cardona, an expert on HPAI at the University of Minnesota, said that the nation is at a crucial moment for preventing an H5 pandemic.

“We are in the spillover stage,” she said, referring to events where viruses are transferred from one species to another. She said a lack of personal protective equipment use and other controls in places like milking parlors creates more opportunities for human cases.

“Because we have a number of barriers to reducing spillover infections, it becomes increasingly difficult to say that we’re not getting closer to the pandemic stage,” she said.

Immunization crucial for protecting egg farms, preventing pandemic

Experts say vaccines could be critical for the egg industry. They could help hens avoid infection and allow farmers to cull only parts of their flocks when H5 is detected.

The meat bird industry has resisted vaccination, arguing it could harm exports.

“Most countries, including the US, do not recognize countries that vaccinate as free of [bird flu] due to concerns that vaccines can mask the presence of the disease,” Tom Super, a spokesperson for the National Chicken Council, told CNN.

Meanwhile, egg producers may want a vaccine that can be administered in food or water so they don’t have to give shots to millions of birds.

Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. told Fox News farmers “should consider maybe the possibility of letting it run through the flock so that we can identify the birds, and preserve the birds that are immune to it.”

Cardona said such a strategy would hurt farmers and consumers, pointing out that turkeys raised for meat and laying hens are not used as breeding stock. Therefore, any selection for disease resistance would not result in chickens better able to withstand H5..

“If we were to do that, we would not only see a recession, we would see a famine,” she said.

Since H5 is primarily spread by wild birds that will continue to harbor the virus, producers won’t be able to substantially reduce infections without vaccination, Cardona said.

Kennedy told Fox News that vaccinating birds could turn them into “mutant factories.” But Cardona pushed back, saying that while vaccination might increase the virus’s mutation rate in some cases, it would reduce the overall risk of the virus breaking through into livestock and developing harmful mutations.

She pointed to pigs as an example — vaccinating them has been shown to reduce both infections and reassortment, the process where two or more viruses exchange genetic material and potentially become more harmful.

“Immunizing poultry flocks would lower the risk of mutations, reduce transmission, and protect humans,” she said.

Currently, if H5 is detected on a farm, producers must kill all birds — even if they’re housed in separate buildings — to contain the virus. But part of the USDA’s plan to address highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) is to limit the scale of these mass cullings.

Michelle Kromm, a veterinarian and consultant specializing in poultry and human health, says vaccines would be critical for a culling strategy to work.

“Without a vaccine, it’s probably not going to be very successful,” Kromm said. “The main source for the virus on a farm, once a barn becomes infected, is that infected barn.”

She said that the large numbers of animals in these barns can “produce an astonishing amount of virus. Most infected birds will die in three to five days if they aren’t culled, she said.

Large-scale cullings can affect employees and surrounding communities. Last spring, when H5 hit its facilities in Ionia County, Herbruck’s Poultry Ranch, Michigan’s largest egg farm, laid off 400 workers, or 40% of its staff.

Cardona said the business model for large poultry farms may need reevaluation. These large farms are efficient and cost-effective for producers, but fail to account for the risk of needing to cull such large numbers of birds when H5 is detected, she said.

Producers already employ other strategies to prevent outbreaks. These include biosecurity measures like requiring employees to park cars off farm property, change clothes before entering barns, and shower before and after entering facilities to reduce the spread of H5, according to Nancy Barr, executive director of the Michigan Allied Poultry Industries, an industry trade organization.

What’s behind high egg prices?

Egg production by state. (Map by U.S. Department of Agriculture)

The average city’s retail price for a dozen eggs spiked to a record high of $5.89 in February.

Experts warn that replacing birds lost to H5 will take months, leading to continued pressure on egg supplies and high prices. Young hens need to be at least 16 weeks old before they begin laying.

Kromm said there isn’t enough commercial breeding stock available to replace the many chickens lost to bird flu. Impacts on facilities raising young hens compound such losses– for example, an Indiana facility raising young hens was forced to cull 1.3 million birds in March.

“Because of the number of hens that have been depleted … consumers can expect to feel this price increase in commercial eggs for quite a period of time,” Kromm said.

Some have questioned how much the spike in egg prices is due to avian flu. A Food and Water Watch report found that monthly egg production in 2022 declined by no more than 5.6%. Yet, average prices jumped 150%, from $1.93 per dozen in January 2022 to $4.82 in January 2023.

“The more concentrated a market is… the more that prices can be artificially inflated,” said Amanda Starbuck, research director at Food and Water Watch. Consolidation in both the egg production and grocery industries allowed companies to pass on high prices to customers with less competition, she said.

The Food and Water Watch report focused on Cal-Maine Foods, a producer that supplies about 20% of the nation’s eggs. Cal-Maine is the only major egg producer that’s publicly traded, giving the FWW insight into the company’s financial data.

The report found that Cal-Maine, the country’s largest egg producer, made over $1 billion in windfall profits during its 2023 fiscal year, even though none of its facilities were hit by avian flu. According to the report, most of those profits came from raising prices significantly: nearly three times higher for regular eggs and roughly one-third higher for specialty eggs.

Cal-Maine did not respond to a request for comment.

Jada Thompson, an agricultural economist at the University of Arkansas, told Planet Detroit that the decline in production largely explains egg prices. Constrained supply is coupled with an “inelastic” demand from both retail consumers and institutional buyers who are willing to keep buying eggs at higher prices, she said.

Thompson added that consumers might also be looking to buy more eggs because they’re concerned about scarcity, comparing this behavior to the run on gas following 9/11 or toilet paper purchases at the beginning of the COVID pandemic.

Rising fuel and feed costs as well as biosecurity measures needed to protect against H5 could also be adding to egg prices, the Associated Press reports.

Spring and fall bird migrations could add to bird flu threat

Spring and fall bird migrations could add to the H5 threat as birds congregate in areas near farms and mix with waterfowl, which are key hosts for the virus.

In the Great Lakes region, a combination of migratory bird flyways, waste grain missed during harvest, and abundant lakes and reservoirs attracts large numbers of migrating birds—and potentially high levels of avian flu virus, says Matthew Hardy, a waterfowl ecologist and co-founder of Agri-Nerds, a company that tracks bird movements to help farms prevent outbreaks.

Hardy pointed to Darke and Mercer counties in northwest Ohio, near Dayton, as areas where some of these factors may have contributed to major outbreaks in poultry facilities in late 2024 and early 2025.

“There’s going to be continued outbreaks and likely mass die-offs in places where birds stage,” Hardy said, referring to the areas where birds come together and rest during migration.

Wetland loss could make this issue worse, pushing birds closer to farms.

Changing temperatures, weather patterns, and human activity have driven the loss of natural wetlands that waterfowl and other species depend on, Hardy said. This has brought them closer to farms as they search for food and suitable habitat. The rate of wetland loss, primarily driven by agriculture, has increased in recent years in the Upper Midwest, Grist reports.

Cardona, with the University of Minnesota, said fall may pose a more significant threat for disease spread than spring. Birds flying north in spring often have some immunity from exposure to viruses the previous year. But those hatched in fall don’t have immunity and may be more vulnerable and likely to spread the virus, especially in the Upper Midwest.

“The birds are breeding and propagating up near the Arctic Circle or in colder areas … As they fly south, those birds mix and mingle and share and reassort viruses,” she said.

Birds develop antibodies on their southward migrations, reducing the amount of virus they shed over time, Cardona said. This could explain why so many H5 outbreaks occurred in the upper part of U.S. flyways in states like Minnesota, Michigan, and the Dakotas, which also have large numbers of turkeys and laying hens that are especially susceptible to H5.

She emphasized the difficulty of making predictions about H5.

“The only predictable thing about influenza is that it’s entirely unpredictable,” she said.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Wetlands rules face rollback under Trump: Great Lakes pollution next?

‘None of us saw this coming’: Michigan confronts bird flu in cows

Featured image: Flock of egg laying domestic hens with brown feathers standing on floor of poultry farm shed with cages in daylight against blurred reflecting background. (Photo Credit: iStock)