A few months ago, I was riding on Amtrak’s new Borealis line from St. Paul, Minn., to Chicago. The train was packed that day, and the new line has proved popular.

My coach seat was much nicer than any airline. Plus, I didn’t have to go through security. The ride was pleasant, with a nice view. But it was also slow. This line takes about seven and a half hours to travel between St. Paul and Chicago — an hour and a half longer than driving, and about five times longer than flying.

St. Paul and Chicago are about 350 miles apart. In Spain, Barcelona and Madrid are about 315 miles apart. Flights between both pairs of cities are about an hour and half. But by train, you can travel from Barcelona to Madrid in just two and a half hours. In part, that’s because the top speed of Spanish intercity trains is more than 190 mph, while the Borealis line tops out at just 79 mph.

Currently, the U.S. has the fastest trains in the Americas. We’re the only country in this hemisphere with trains that can go at least 200 km/h (125 mph). But if you look to Europe, Asia and a couple of countries in the Middle East and North Africa, we’ve fallen behind. Nations from France to Indonesia to Morocco have all built rail lines that can travel at least 250 km/h, (155 mph).

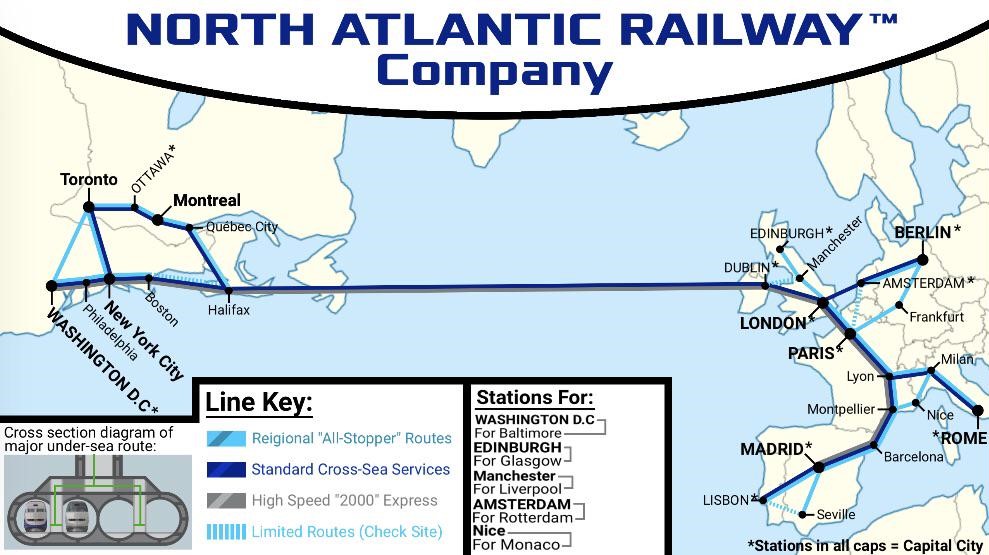

Reddit user EmeraldX08 posted a map of a trans-Atlantic HSR tunnel, which they said was inspired by a dream. (Photo courtesy of EmeraldX08)

Proposals do exist for several high speed rail (HSR) lines. And a planned upgrade to Amtrak’s Acela line should let us into the 155 mph club soon. But what about a bigger HSR network, especially one that includes the Great Lakes region? Proposals abound, ranging from relatively grounded research projects to maps posted on social media by starry-eyed railfans.

What would it take for us to join the world of bullet trains? Would it even be worth it?

To start off, it’s helpful to define what “high speed rail” even is. There are some pretty fast trains in the U.S. already. In the Midwest, Amtrak’s Chicago-St. Louis and Chicago-Detroit lines can go up to 110 mph. Brightline’s Florida service can go up to 130 mph. And the Acela line, which travels from DC to Boston, reaches 150 mph, and will hopefully go as fast as 160 mph soon.

“We’re already, daily, operating at speeds well in excess of what you can legally drive,” said Marc Magliari, an Amtrak spokesperson based in Chicago.

Rick Harnish is co-founder and executive director of the High Speed Rail Alliance, a Chicago-based advocacy group. When I asked him to define HSR, he said, “I don’t know. How do you define art?”

“I think for most people, ‘high speed rail’ is equivalent to saying ‘a train that I want to ride,’” said Harnish. He said that the speed difference you need in order to create “a dramatic ridership shift away from driving is about half of the time it takes to drive.”

A vision for an integrated high-speed passenger and fast freight railroad network. (Map courtesy of Dylan Hayward/High Speed Rail Alliance)

Others are more precise with their definitions. Some say that “high speed” starts at 125 mph. But others say those trains are merely “higher speed,” and that true HSR begins around 155 mph. The International Union of Railways, an industry group, says that in general, 155 mph is the dividing line.

China dwarfs other countries in the scale of its HSR network, with more than 20,000 miles of track. The next-most expansive network is Spain’s, which is only about one-tenth the size. However, the Chinese experience may be hard to replicate in the U.S.

In part, this is because Chinese HSR stations have often been built in unpopulated areas.

“There’s no existing occupiers to kick up a fuss,” said Richard Bullock, an Australian consultant who has worked on more than 50 railways around the world, including 7 Chinese HSR projects.

In addition, mainland China’s authoritarian government helps them build more quickly by avoiding checks and balances.

“Whether it would work in a more democratic, with a small D, country is another matter,” said Bullock.

Workers generally have few rights in China, and Chinese train manufacturers have been accused of using forced labor.

One positive aspect of the Chinese HSR projects that Bullock worked on was consistent leadership. The “project manager never changes, so there’s never any ability to shuffle the blame to the previous project manager, and all that sort of thing,” said Bullock. “Their projects, all the ones I was involved in, always came in on time and on budget. Well, they manipulated the budget…but they weren’t far off.”

A key difference between the U.S. and Europe is size. The Schengen Area, an open-border zone comprising 29 European countries, has an area of about 1.77 million square miles. By contrast, the contiguous US is about 3.12 million square miles.

Forks in the Railroad

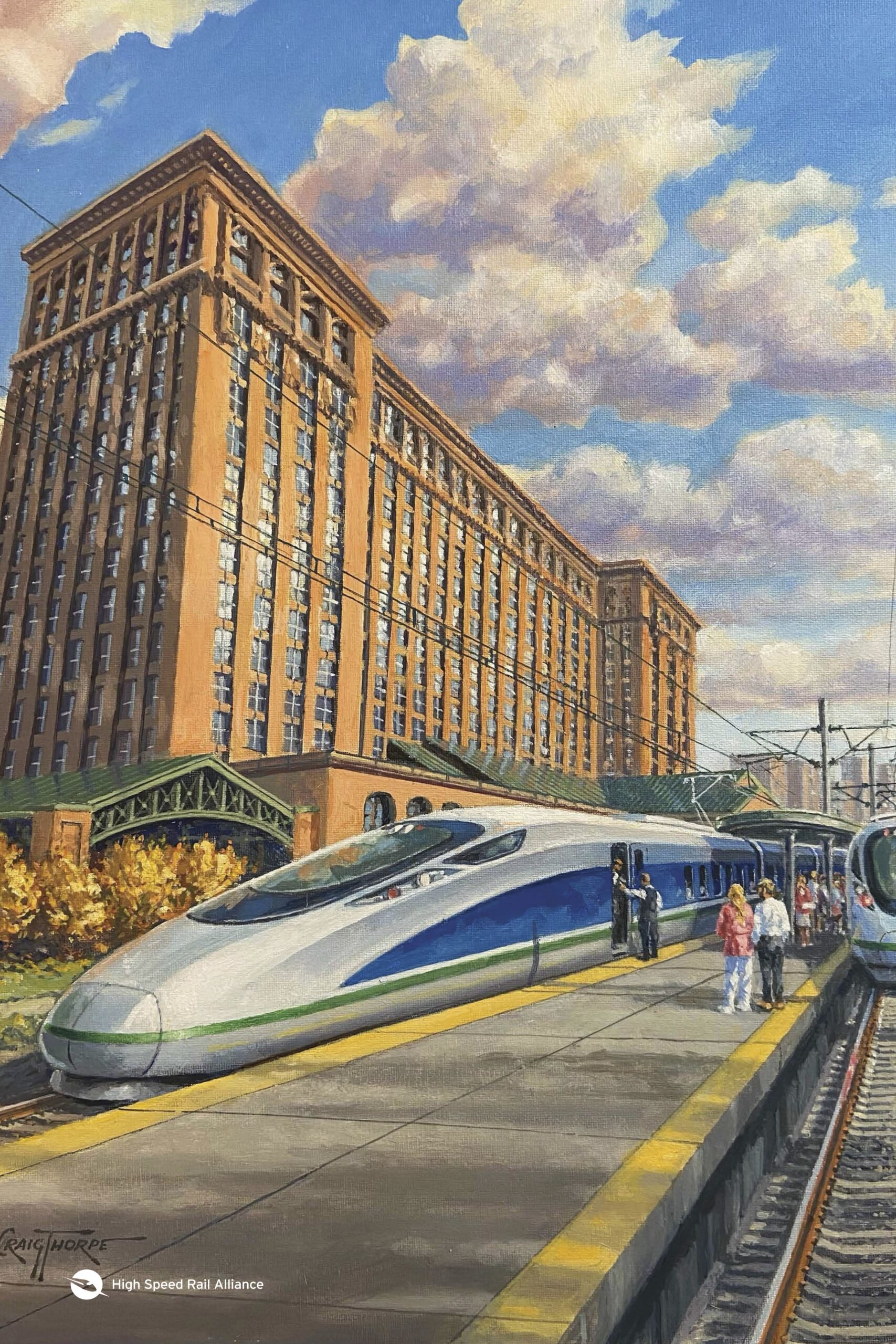

A vision for a electrified, passenger-dedicated trunkline to and through Chicago. (Illustration courtesy of Dylan Hayward/High Speed Rail Alliance)

“The U.S. rail network was privately developed, with some government incentives, dating back to the 1850s. Those were always private companies that were given government charters, in some cases land grants, in some cases payment, to build from one place to another, and had a strong freight orientation first, and a passenger orientation second,” said Marc Magliari, an Amtrak spokesperson based in Chicago.

“The European rail network was primarily government-developed and was passenger service-oriented from the beginning, and with very strong government investment from the beginning, because they were primarily state-owned,” said Magliari. “In the U.S., the network was developed freight-first and developed by companies who were laying out their railroads. They had to meet some standards, but they were laying out their railroads in the 19th century to be built easily and quickly.”

The case for trains at Michigan Central Station. (Illustration courtesy of Dylan Hayward/High Speed Rail Alliance)

Today, most Amtrak lines run on tracks that are owned by private freight railroads. In order to create true high speed rail, a new track would likely have to be built — an expensive prospect.

“What you’re doing with high speed rail is basically building a network of rail, publicly owned, the way the Eisenhower interstate [highway] system was started in the ‘50s,” said Magliari. “That was primarily federal support, just like the aviation network we have, where most of the airports are publicly owned.”

However, the level of subsidy varies, according to Baruch Feigenbaum, who studies transportation policy at the Reason Foundation, a libertarian think tank.

According to Feigenbaum, train travel is subsidized at a significantly higher rate than planes or cars. He cited studies by the Bureau of Transportation Statistics, part of the U.S. Department of Transportation, and the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank.

Rather than building HSR, Feigenbaum supports expanding other modes, such as highways, airports and buses. He argues that HSR can only truly be competitive for cities that are between 200 and 500 miles apart.

Economic and Environmental Impact

Even supporters of HSR emphasize the need to pick the right routes. In the U.S., the Northeast corridor is a favorite, because it has many large cities relatively close together. An HSR connection between Los Angeles and San Francisco is in development. This route is also a popular choice, since while these cities are far apart, they are both major centers of population and economic activity.

However, the Great Lakes region also has a big economy and its fair share of big cities. Harnish argues that HSR could transform the region.

“It is perfectly reasonable to think that if we had high speed rail, it would be two and a half hours from St. Paul to Chicago, with stops in, perhaps, Madison and Milwaukee, and perhaps Eau Claire and/or Rochester. Each of those places would become much stronger,” he said. “But it’s not just those places, because then it moves people out of cars, which means you’re spending a lot less money on parking lots. It means that within the cities, the buildings can be closer together, which means you’re spending money on utilities and a postal service, etc. It means that people are walking around more, which means people are interacting face-to-face better.”

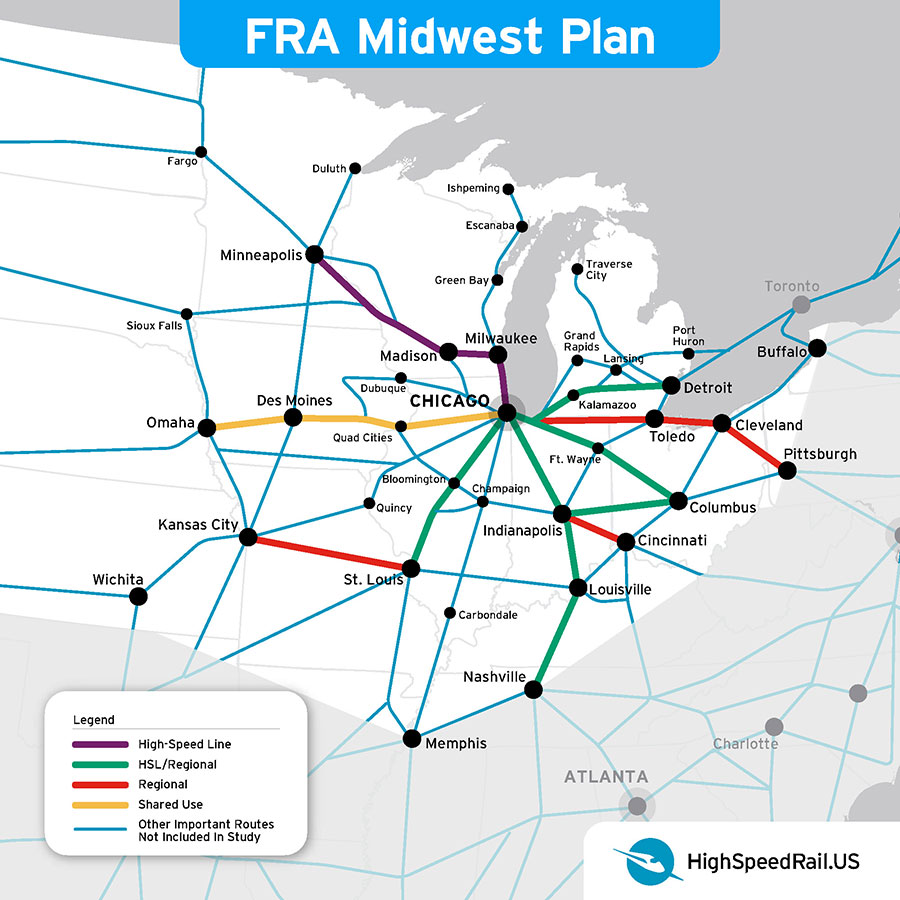

High-speed rail in the Midwest. (Map courtesy of Dylan Hayward/High Speed Rail Alliance)

HSR could have environmental advantages as well. There is some evidence that it could reduce carbon emissions, although others dispute this.

“A single railroad track has the capacity of about 10 highway lanes. So that’s a 10-to-1 ratio,” said Harnish. “A lot less fuel being burned.”

Feigenbaum concedes that there could be some environmental benefit, at least for now.

“It’s true to a certain extent now, but not totally,” he said. “But I also am not sure it’s going to be true in the future. High speed rail is largely electrified. Planes use oil, basically. Every day, it seems like there’s a new startup or prototype testing not using oil. Electricity, or some form of alternative.”

In 2023, a sustainably-fueled plane flew across the Atlantic Ocean.

Mikhail Chester is an engineer at Arizona State University. He supports HSR and thinks it could have environmental benefits, but it should be designed so that people will actually ride it.

“A public transportation system is not trying to cater to a very small number of people, it’s trying to cater to a much broader group of the population,” he said. “But in order to get that higher ridership, you’re going to have to route these trains such that they go to places where you’re going to pick up all of these people.”

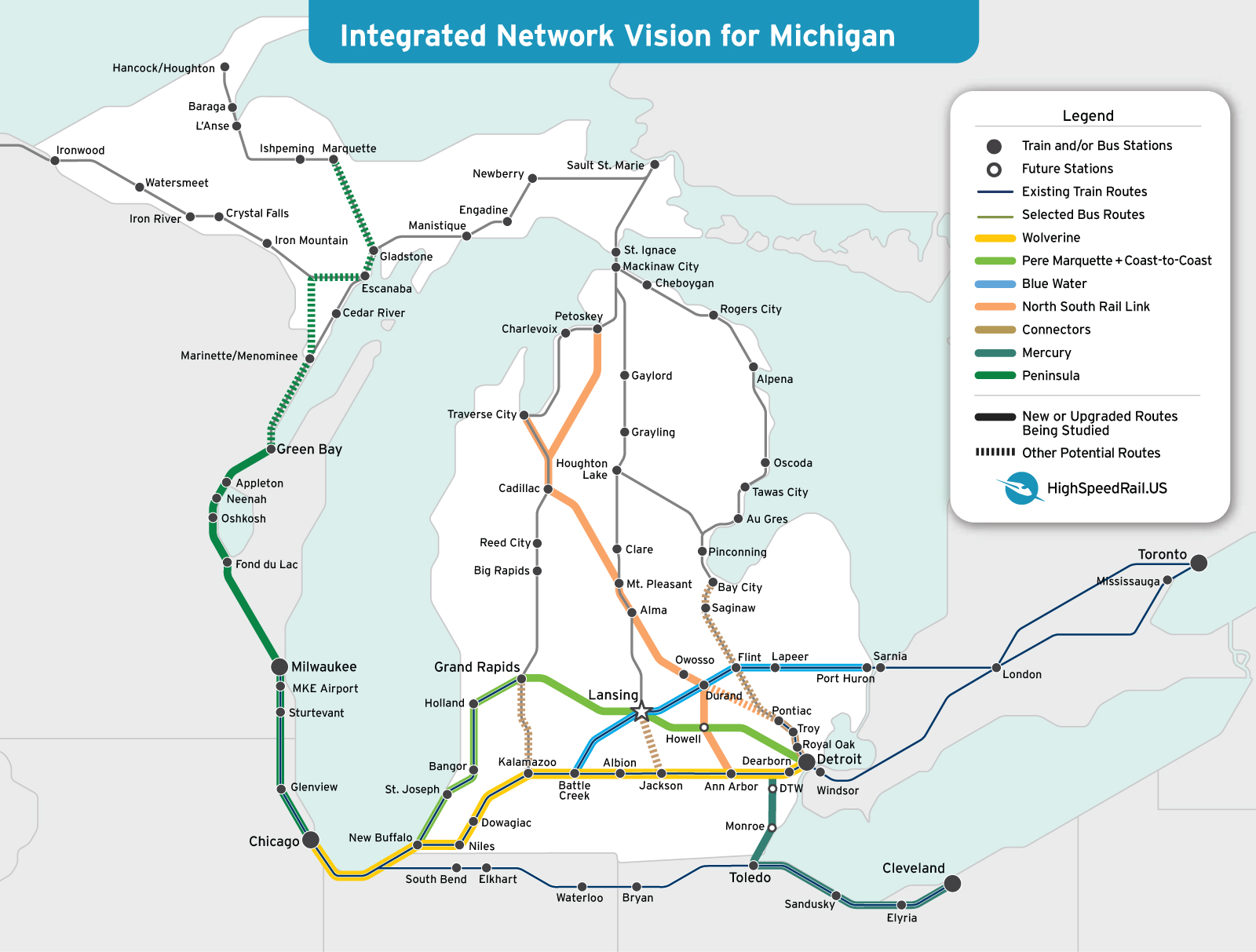

An integrated network vision for Michigan. (Map courtesy of Dylan Hayward/High Speed Rail Alliance)

Another issue is money. Bullock argued that the government should pay the initial costs, but a good HSR project should be able to pay for its own operation and maintenance through fares and other revenues.

“I think if the project is going to be successful, you’ve got to start with a clear mind about who is going to be paying for it,” he said. “That’s not to say that government shouldn’t pay. That’s not a hanging offense, as it is in your country. But people do need to realize or accept that a lot of the capital is going to have to come from the public sector.”

In addition, HSR could benefit the economy, although exactly how much is unclear.

“In terms of the economic debate, I think the argument for there really being additional benefits rests on various forms of agglomeration benefits, which is the impact on productivity of making jobs and workers more accessible to each other,” said Chris Nash, an economist at the University of Leeds in England.

However, not everyone might benefit. Roger Vickerman, an engineer at Imperial College London, argued that cities with populations under 100,000 could lose out to bigger cities with better service.

“The majority of people want to go from the big city to the big city,” he said, and so these smaller cities may not have as good HSR service. “The intermediate cities very often may suffer because they may have had very good communication before, but they get bypassed.”

Regardless of what the evidence says, “there’s something about trains that I think most people consider sexy,” said Feigenbaum. “Certainly sexier than, say, buses.”

While the potential for high speed rail in the Great Lakes region is unclear, HSR’s potential benefits and its sci-fi image mean it will likely continue to play a role in our conversations about the future of transportation.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

The fascinating history of the Great Lakes Yemeni sailors

Featured image: A vision for a electrified, passenger-dedicated trunkline to and through Chicago. (Illustration courtesy of Dylan Hayward/High Speed Rail Alliance)