On March 14, Ohio gubernatorial candidate Vivek Ramaswamy said that perhaps Lake Erie should be changed to Lake Ohio.

According to reporting from Cleveland.com:

“Anybody think if there’s a Lake Michigan, maybe there should be a Lake Ohio around here?” Ramaswamy said, about 13 miles away from Lake Erie. “I’m feeling that. We’ll talk about that a little bit more as this campaign progresses.”

Ramaswamy said this at a GOP fundraiser in suburban Toledo. The Cincinnati Enquirer reported on March 17 “he was joking,” but prompting the initial statement, Ramaswamy talked about the advantages of Ohio’s proximity to Lake Erie and mentioned Trump’s decision to rename the Gulf of Mexico to the Gulf of America.

Neal Rubin, American cartoonist and columnist for The Detroit Free Press, said in a recent op-ed: “That sounds more like a trial balloon than a punch line.”

Edith Olmsted wrote in the New Republic: “And while many may had hoped that Trump was only joking about changing the name of the Gulf of Mexico to the Gulf of America, that’s exactly what he did on his first day in office.”

This is not the first time in recent history that jokes were made about renaming one of the Great Lakes. In February, Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker made a comment about renaming Lake Michigan to Lake Illinois.

What’s in a name?

According to the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy (EGLE), Lake Erie received its name from the Eries, a Native American tribe who once lived on the southern shore of the lake. “Erie” is shorthand for the Iroquoian word erielhonan, meaning “long tail.” From about 2,000 B.C. to 1700 A.D. Native Americans lived, hunted and fished on this lake.

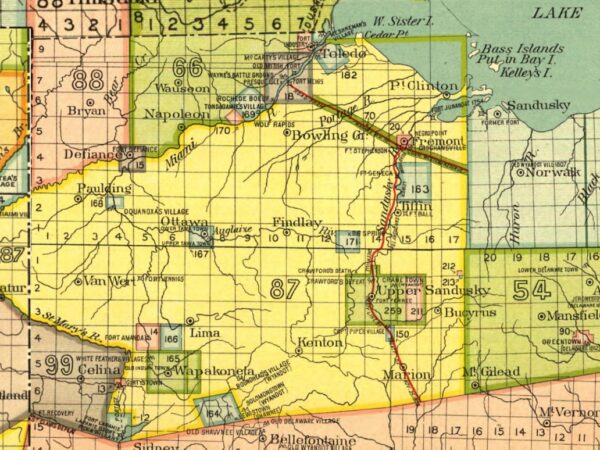

When looking at history, changing the names of the Great Lakes is not completely unheard of. In a map made in 1712, Lake Ontario was known as Lake Frontenac, named after the French soldier and Governor General of New France.

Of course, before that, there were the names that Native Americans gave the lakes. For instance, Lake Superior was (and is still referred to) as Gitchi Gumee. Lake Huron was once labeled as Lake Karegnondi on a 1656 map by Nicolas Sanson. “Karegnondi” was thought to be what the first inhabitants, referred to as the Wyandot (also known as Huron-Wendat) by French explorers, called the lake. Karegnondi is thought to mean “Lake of the Hurons,” “Freshwater Sea” or “lake.”

In today’s world, according to additional reporting from the Cincinnati Enquirer, there must be a compelling reason before “a proposal to rename a natural feature should be submitted to the U.S. Board on Geographic Names.” Also noting that it would take at least six months, “allowing time for consultation with states, tribes, mapmakers and other interested parties.”

What’s the impact?

According to The Conversation: “People in power have long used place naming to claim control over the identity of the place, bolster their reputations, retaliate against opponents and achieve political goals.

These moves can have strong psychological effects, particularly when the name evokes something threatening. Changing a place name can fundamentally shift how people view, relate to or feel that they belong within that place.”

The Conversation authors went on to discuss how when different leaders take power, and frequently change the names of places or geographic landmarks, that can lead to confusion in a never-ending name game. Identity and security are very much tied to our sense of place. They suggest an alternative: what is the renaming of landscapes was actually participatory?

For more on this specific cultural impact and the history of renaming bodies of water in the Great Lakes region, check out our July column of Nibi Chronicles.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

From the Ice Age to Now: A Lake Erie timeline

Featured image: Cleveland, Ohio near sunset, viewed from out on Lake Erie. (Photo Credit: iStock)