Just-announced staff cuts and hiring freezes from the Trump administration will jeopardize the ongoing success of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s (USFWS) decades-long battle against sea lamprey, according to officials. While states, provinces and U.S. and Canadian tribes are involved in the labor-intensive efforts, the USFWS performs most of the in-stream treatments in the U.S. Ironically, the cuts come just as Invasive Species Awareness Week arrives the last week of February.

In November, The Great Lakes Fishery Commission’s (GLFC) Lake Superior Committee announced that lake trout, a popular fish nearly exterminated by sea lampreys and overfishing in the mid-1900s, has fully rebounded. The committee’s scientists estimate the current lake trout population in Lake Superior is now at or above what it was before sea lamprey made their way through the Welland Canal.

According to the GLFC sea lampreys, native to the Atlantic Ocean, had been observed in Lake Ontario as early as 1835, with Niagara Falls providing a natural barrier to the other Great Lakes. It’s believed they entered Ontario through the Erie Canal, completed in 1825. But it was after improvements were made to the Welland Canal in the late 1800s and early 1900s (connecting lakes Ontario and Erie) that sea lampreys began feeding on fish in the other Great Lakes.

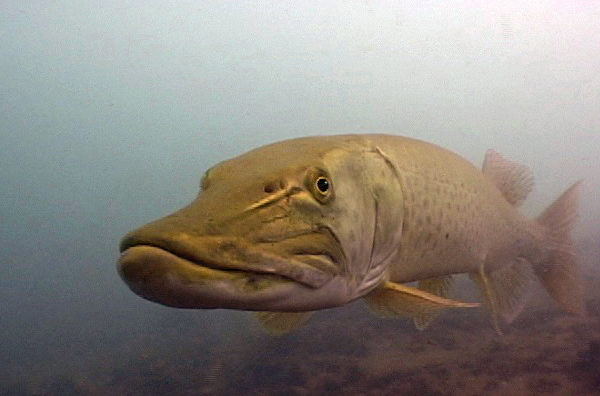

While there are several smaller, native lamprey species in the Great Lakes, parasitic sea lampreys are larger and much deadlier consumers of fish. After hatching in streams and spending up to two years feeding on microscopic food sources, they develop a large, circular mouth filled with dozens of sharp teeth. At this point they’re ready to enter lakes and feed on fish for a year or longer by attaching themselves with their suction cup mouths and boring a hole with their teeth. They suck blood and nutrients from their host fish, either killing or weakening them. The lampreys then return to streams to spawn before they die.

While sea lamprey populations had been around for decades, they exploded in the late 1940s, nearly wiping out lake trout, whitefish and cisco — the main targets of commercial fishing operators. Up to 15 million pounds of lake trout were harvested annually from the upper Great Lakes prior to the 1940s. But by the 1960s, the harvest had dropped by 98% to just 300,000 pounds according to commercial fishing records. Operators reported 85% of the fish they caught bore lamprey wounds.

“When we first started the effort to control lamprey at their height they were taking over 100 million pounds of fish every year,” said Greg McClinchey, director of policy and legislative affairs at the GLFC. “To put that in perspective, they were outcompeting humans for the resource. There aren’t many creatures that can claim to be more harmful than humans when it comes to this type of thing and lampreys are exactly that.”

While officials in the U.S. and Canada, including tribal nations, knew something had to be done, they weren’t sure exactly how to do it.

A chemical solution was found, after various methods tried to kill sea lampreys

Invasive sea lampreys. (Photo courtesy of USFWS)

By 1955, commercial fisheries had collapsed and the GLFC was established with the sole responsibility of managing the sea lamprey problem, beginning with Lake Superior.

Previous efforts had focused on collecting and killing sea lampreys in streams using weirs and electrical barriers. Both efforts were ineffective. Researchers continued work begun in 1953 to find a chemical that would kill sea lampreys but not harm other fish, wildlife, humans or affect farmers’ irrigation water.

After testing more than 5,000 chemical compounds at the Hammond Bay Biological Station on Lake Huron in northern Michigan, researchers finally found a chemical, 3-trifluoromethyld-4-nitrophenol, or TFM. It was the first version of compounds now referred to collectively as lampricides. And they worked, killing most lamprey in streams where they spawned and where the juveniles hatched and lived before moving out to lakes.

In the more than six decades since, lampricides have been the go-to method for controlling the fish-killing lamprey. A full-length documentary by Skyhound Media directed by Lindsey Haskin chronicles the history of Great Lakes fisheries and the subsequent rise and decline of sea lampreys. The award-winning The Fish Thief, eight years in the making, was released in 2024.

While the film documents the full story of sea lampreys, it also delves into the invasion of alewives from the Atlantic Ocean in the 1960s. Eventually, that Great Lakes fisheries disaster culminated in the introduction of salmon species to the lakes, and soon after, the rise of recreational fishing. Those events laid the foundation for the amazing fishing industry that’s now hosted on all the lakes.

Lessons from pandemic disruptions

“During the COVID period borders were closed, social distancing was required and there were all sorts of impediments to our programs and for two years we weren’t able to complete a full control program,” McClinchey said. “So in some places we’ve seen lamprey populations go up by 300 percent. Fortunately, that’s an increase from our low point.”

He explained that the skyrocketing population in select areas is proof that the lampricide program works, although it was an “experiment” that fisheries managers would never have tried.

“Mother Nature kind of threw this at us and we can see the results. It reminds us that sea lamprey are a coiled menace. Currently we kill about 8 or 9 million a year,” McClinchey said, going on to mention that since their peak more than a half-century ago, lamprey populations are down about 90%.

While populations are down dramatically, he said it’s not feasible to attempt tracking down every last sea lamprey. But there is a new development on the horizon.

New hi-tech weapon from Michigan State University

Invasive sea lamprey on lake trout. (Photo courtesy of A. Miehls/GLFC)

While removing dams has become fashionable around the nation, reconnecting fish to upstream habitats long unavailable, it presents its own challenges.

“Fish like salmon and others could move upstream, but that would cause very real problems in controlling sea lamprey,” said Michael Wagner, associate professor at Michigan State University’s (MSU) Department of Fisheries and Wildlife. “When sea lamprey populations rebounded after COVID, the commission and their partners started thinking about selective fish passage. How can we design devices or fishways that could facilitate the movement of native and desirable fishes through them while blocking invasive species like sea lampreys from going through?”

Enter FishPass, a concept that’s being developed by MSU and partners and constructed on the Boardman-Ottaway River, which is undergoing a complete ecological restoration with the removal of three dams. The first FishPass project is being constructed on the river in Traverse City and will serve as a full-scale field test.

Wagner said he expects artificial intelligence will play a role in determining which swimming creatures get a pass through underwater gates and which won’t.

“We need a system that can reliably detect whether this is a sea lamprey and not a stick or something else,” he said. “This is a fish that changes shape because it’s eel-like so it could be a circle in one image or a straight line in another, they could be crossing each other or another fish in there. I suspect that’s where AI will play a role.”

Wagner said if the concept is perfected it can be widely adapted.

“It’s a project of global significance and we’re in it for the long haul,” he said. “It’s a slow development where we’re going to think it out and get it right. It’s an example of how the Great Lakes can be a crucible to creating solutions for really difficult problems that are shared around the world.”

Lampricides and in-stream searches will continue

According to Wagner, the tried-and-true method of searching out spawning sites and treating with lampricides will continue because it works. But the new FishPass technology will augment those efforts in the future and help facilitate the removal of dams in Great Lakes tributaries.

The hardest-hit fish species, lake trout, have returned to Lake Superior in abundance, and McClinchey cites that as evidence of success.

“We’re confident we’re already seeing sea lamprey numbers going down and we think things will be back where they were in relatively good step,” he said. “FishPass is a smart dam and once it’s completed in Traverse City, it will sort fish in real time. If this works it will change the face of dams not just in Michigan and the U.S., but globally. We’re very excited about what this means for us and the Great Lakes.”

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Great Lakes most unwanted: Top 10 invasive species

Finding creative new ways to manage invasive cattails

Featured image: Invasive sea lampreys. (Photo courtesy of D. Brenner/SNRE)