Ryan Schwegman is a relocation specialist but don’t ask for his help if you’re moving, unless you are an endangered species.

Schwegman is COO of BioSurvey Group, LLC. in Oxford, Ohio. He manages a team of commercial and scientific divers who travel across the Eastern United States, relocating threatened and endangered species before river restoration projects begin.

“Just this year I’ve been in the Adirondacks in New York, Mississippi River in Iowa, Ohio, Michigan,” Schwegman said. “We pretty much travel all over the place to do this.”

Most river restoration projects aim to return rivers to more natural conditions with ripples, rapids, and the free movement of species. But as anyone who has lived through a renovation knows, when construction begins, things generally get a lot worse before they get better.

While demolition might be fun for contractors and TV personalities, it can be intolerable for some residents to live through.

Fish, turtles, birds and other mobile species can move to other areas of the watershed while river restoration work is underway. Most will return when the project is complete.

But what happens to the species that cannot relocate themselves? That’s when Schwegman and his team step in.

To learn more, tune in to this month’s Great Lakes Now segment about efforts to save native mussels — airing Monday, January 27 on all PBS platforms.

Livers of the River

Freshwater mussels nestle into the bottom and spend their entire life, which can last several decades depending on the species, in one spot. They have a muscular appendage called a foot which they can extend to anchor themselves to the bottom or to move short distances. But adults don’t move much or very far.

Freshwater mussels can use their foot to travel short distances. Image by Greg Lashbrook

Mussels feed by filtering large quantities of water, which they continuously pump through their bodies to feast on plankton and other small organic particles. This filtering process helps to keep rivers clean.

“They’re kind of the livers of the river,” said Heidi Dunn, a malacologist and founding member of the Freshwater Mollusk Conservation Society, which is a non-profit group comprised of freshwater mollusk conservationists from around the world.

“Freshwater mussels are an integral part of our riverine ecosystem,” Dunn said.

In addition to filtering, mussels help rivers in several ways.

Mussels assist in keeping the substrate healthy. One way they do this is by stabilizing the bottom. Well-anchored mussels can withstand high-water events, which in turn helps to keep the bottom more secure. Their movements also aerate the substrate, similar to earthworms in a garden.

Mussels are a key component in the aquatic food chain. They take nutrients out of the water column and excrete them into the river bottom, where they are available for invertebrates, which are the base of the fish food chain. Mussels themselves are also a favored food source for mink, muskrats, otters and raccoons.

Like canaries in a coal mine, mussels act as an early warning of trouble. They are among the first to experience ill effects from pollutants, making their well-being a direct indication of the river’s overall health.

“If you have a good mussel population down there, you have a functioning river system,” Dunn said.

Before 1900, North American rivers had the highest diversity and density of freshwater mussels on Earth. Mussels numbered 50 to 100 per square meter on the river bottoms. Today, mussels rank among the most endangered organisms in North America.

So, how did mussels go from being plentiful to threatened?

In a word: buttons. More specifically, mother-of-pearl buttons.

A freshwater mussel shell with 9 drilled buttonholes. Image courtesy of the Grand Rapids Public Museum.

The decimation of freshwater mussel populations in North America began in the late 1800s. John Boepple was a skilled button maker in Hamburg, Germany. After hearing stories of America’s riches, including rivers lined with shells, he set his sights on the Mississippi River.

Mother-of-pearl, which is the lustrous inner lining of freshwater mussel shells, has been used for centuries. Native Americans used shells as bowls for food and ceremonial offerings. The shells were also carved into utensils, tools and stunning jewelry.

In 1891, Boepple opened the first button-making business in Muscatine, Iowa, on the Mississippi River. Other businesses followed, and by 1898 the town produced 138,615,696 buttons earning international fame and the moniker of Pearl City.

Mother-of-Pearl buttons are made from the shells of freshwater mussels. Images courtesy of the Grand Rapids Public Museum

When the Mississippi River mussel populations collapsed from overharvesting, collection operations expanded throughout the Midwest to continue fueling the button-making industry well into the 1900s.

Later in life, Boepple assisted the United States government with efforts to restock and restore mussel populations in the Mississippi River. Unfortunately, unchecked wastewater and industrial pollutants rendered those efforts ineffective.

By the mid-1900s, plastics replaced shells as the preferred button-making material bringing an end to the mother-of-pearl button industry boon in America. But the mussel’s reprieve was short-lived.

The Japanese discovered that beads cut from the shells of North American mussels could be inserted into oysters to produce high-quality cultured pearls. Tons of mussel shells continue to be exported annually from the United States for the cultured pearl industry, although several states now limit mussel collections.

Alluring Partnerships

“The thing that’s special about them is they all require a fish host to complete their lifecycle,” Dunn said.

Except for salamander mussels which use mudpuppies as their hosts.

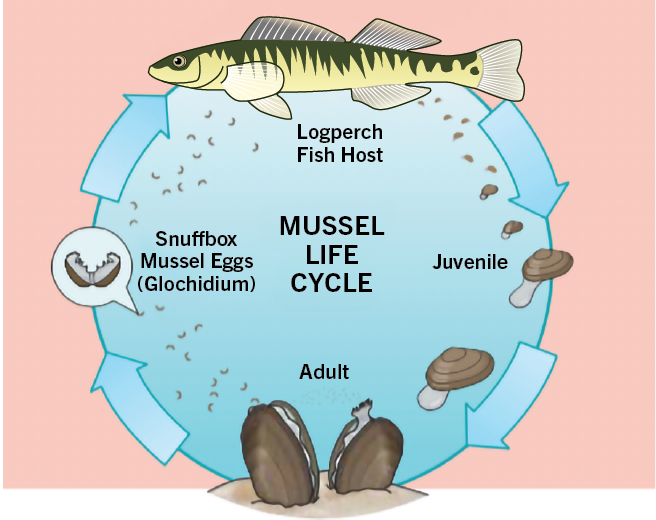

The hosts play a key role at the end of the process. Reproduction begins with male mussels releasing sperm into the water column. Female mussels draw the sperm in and fertilization takes place internally.

The young, called glochidia, are stored in the female mussel’s oxygen-rich gills. She will incubate the glochidia for 2-11 months, depending on the species. When the young are ready, it is time to find a host fish.

Log perch are the only host fish a snuffbox mussel can use. Illustration courtesy of the Grand Rapids Public Museum.

The female mussel’s objective is to transfer the glochidia onto a fish or mudpuppy. To achieve this goal some species use the fleshy part of their mantel to create fairly realistic lures. These lures can imitate small fish, insects and even crayfish.

Some mussels are very specific about their hosts others can use a variety of fishes as hosts. When the host fish strikes the lure, the female releases her glochidia. The glochidia attach either to the gills, as internal parasites, or onto the fins, as external parasites.

Hosting does not harm the fish or mudpuppy. The glochidia become encrusted and remain with the host anywhere from a week to six months. During this time, they transform into minuscule replicates of the adults.

With their metamorphosis complete, the juveniles rupture their cysts and fall to the river or lake bottom. The host fish’s movement ensures the juveniles are widely dispersed on the bottom.

The black dots on this freshwater mussel’s mantle are used to lure host fish closer. Image by Greg Lashbrook

The juveniles immediately burrow into the substrate and remain there for several years. They will eventually work their way up and will remain in the same general area for the duration of their life.

Because mussels are dependent on fish hosts, the variety and abundance of mussels in a river is a direct reflection of the fish diversity. Fish hosts have only been identified for approximately one-third of North American mussel species.

Dams and other structures that restrict access for host fish have been a contributing factor in the overall decline in mussel populations. While removing these barriers benefits mussels, they need to be protected from the improvement process.

“Mussels are out of sight, out of mind, but they’re very important to us,” said Dunn. “We’ve really treated them pretty badly in the past but good mussel beds out there would help clean up the rivers.”

What you can do to help mussels:

- Reduce pesticide use: limit the use of pesticides in your area.

- Control erosion: plant trees and other plants to help keep water clean.

- Clean boats, trailers and motors: prevent the spread of invasive species like zebra mussels.

- Support restoration efforts: participate in restoration projects or support organizations working to restore mussel populations.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

I Speak for the Fish: Why do mudpuppies matter?

I Speak for the Fish: How Native Americans are saving lake sturgeon

Featured image: Freshwater mussels help rivers by filtering hundreds of gallons of water a day. (Image by Greg Lashbrook)