By Ellie Katz

Points North is a biweekly podcast about the land, water and inhabitants of the Great Lakes.

This episode was shared here with permission from Interlochen Public Radio.

One calm September morning in 1971, Big Abe LeBlanc got ready to go fishing on Lake Superior.

This was something he often did in secret, under the cover of darkness, hiding from the Michigan Department of Natural Resources.

But on this particular day, Big Abe called the DNR before he left.

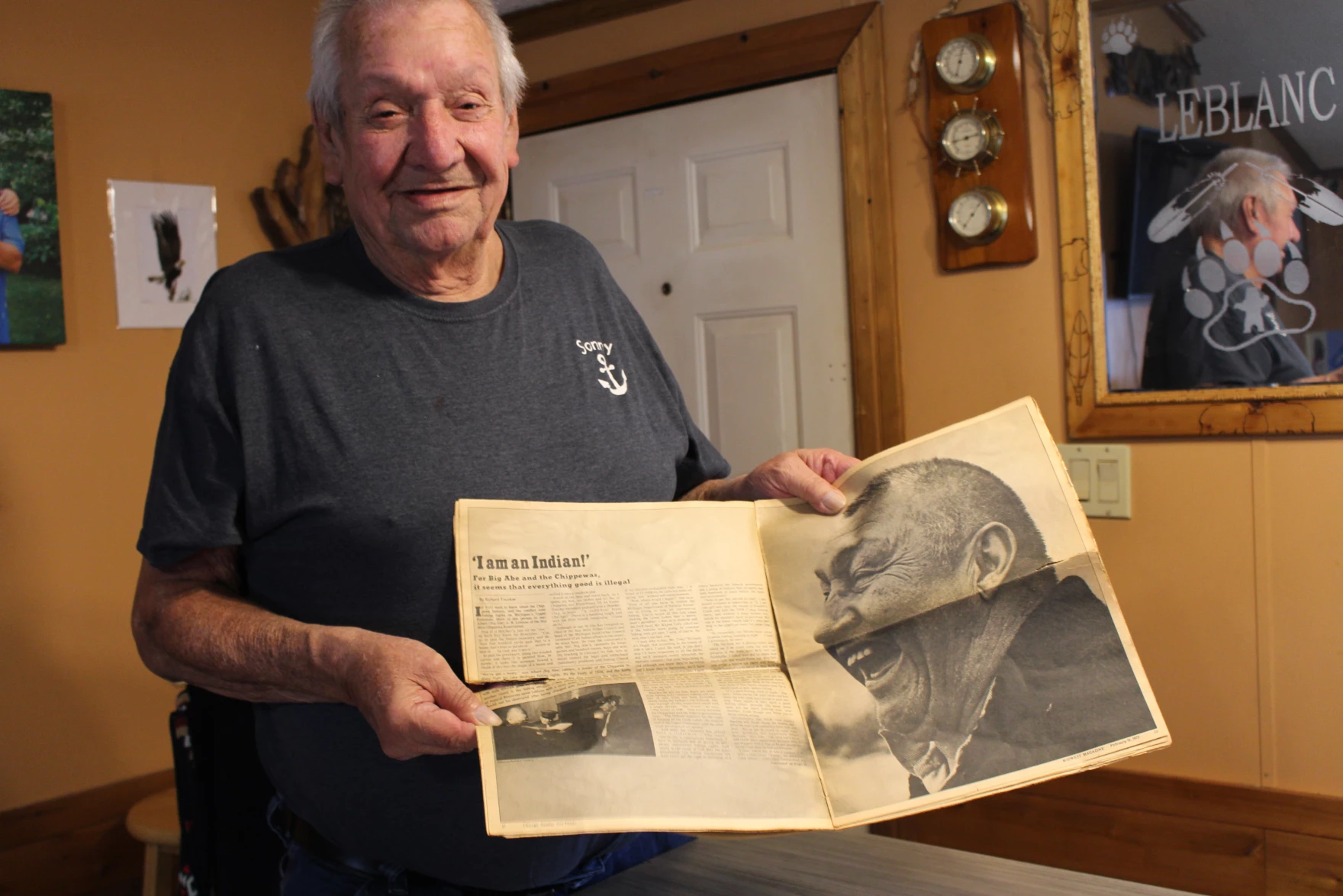

“I just remember him saying that, you know, ‘This is where I’ll be, and if you want me, come get me,’” said his son, Sonny LeBlanc.

It was 1971. And Big Abe, who’s Ojibwe, was preemptively turning himself in for two crimes, at least according to Michigan law. The first crime: commercial fishing without a license. The second: fishing with illegal equipment.

After Big Abe hung up, he went out on the lake, set his nets and waited for the officers to come. What happened next changed fishing in the Great Lakes forever.

CREDITS:

Producer: Ellie Katz

Host: Dan Wanschura

Editor: Morgan Springer

Additional Editing: Ed Ronco, Peter Payette, Dan Wanschura, Izzy Ross

Special Thanks: Corinne Cameron, Gloria LeBlanc, Charles and Nancy Cleland, Jason and Margaret Smith, Jeanne Franklin, Mark Ebener, Kristin Szylvian, Bill Rastetter

Music: Blue Dot Sessions

TRANSCRIPT:

DAN WANSCHURA, HOST: This is Points North, a podcast about the land, water and inhabitants of the Great Lakes. I’m Dan Wanschura.

One morning, Big Abe LeBlanc got up and got ready to go fishing on Lake Superior. This was something he often did in secret, under the cover of darkness, hiding from the Michigan Department of Natural Resources.

But on this particular day, he picked up the phone and called the DNR. His son, Sonny LeBlanc, was there with him.

SONNY LEBLANC: I just remember him saying that, you know, “This is where I’ll be, and if you want me, come get me.”

WANSCHURA: It was 1971. And Big Abe, who’s Ojibwe, was preemptively turning himself in for two crimes, at least according to Michigan law. The first crime: commercial fishing without a license. The second: fishing with illegal equipment.

After Big Abe hung up, he and Sonny drove a half hour to Pendills Bay in Lake Superior. The car ride was quiet. It was late September. The trees were just starting to show bits of fall color.

And when they got there, they pushed their small fishing boat across the sandy beach and went out on the water. In front of them was this wide open expanse of Lake Superior. Behind them was Big Abe’s daughter-in-law, Joann LeBlanc, waiting on the beach and watching, with her newborn baby on her hip.

JOANN LEBLANC: It was a– kind of a cool morning. Nice and– the water was nice and calm. And when water is calm like that, you can hear way far away because water carries your voices.

WANSCHURA: Abe and Sonny were murmuring as they set their fishing nets a few hundred feet offshore. Then conservation officers started to show up on the beach next to Joann.

JOANN LEBLANC: I was kind of feeling apprehensive, maybe scared, or whatever, because I didn’t know what it might turn into.

The net Big Abe LeBlanc set on September 28, 1971 was confiscated by conservation officers and returned to the Bay Mills Indian Community in 2023. It rests in a wooden box in the office of Abe’s granddaughter and Bay Mills President Whitney Gravelle, who plans to display the net at the tribe’s headquarters. (Credit: Ellie Katz / Points North)

WANSCHURA: What it turned into changed fishing in the Great Lakes forever. Reporter Ellie Katz takes it from here.

ELLIE KATZ, BYLINE: Big Abe’s name was actually Albert B. LeBlanc. But he got his nickname for a reason.

RUBY LEBLANC HATFIELD: Oh, man, you definitely noticed him. He was like, what? Six-three?

EVELYENE LEBLANC MCPHERSON: No, he was six-six.

RUBY LEBLANC HATFIELD: Oh, six-six, about 350 [pounds].

KATZ: And Big Abe had a big family. These are two of his thirteen kids: Ruby LeBlanc Hatfield and Evelyene LeBlanc McPherson. Here’s Ruby again.

RUBY LEBLANC HATFIELD: And so being a big man, he had a big voice. Every morning, my Uncle Art, his brother, would show up, and they’d have coffee and talk. You could hear them. I mean, we’d be sleeping. I’m talking early, like five, six in the morning, and that was basically our alarm clock, because you could hear them talking regardless of where you were in the house.

KATZ: Abe’s granddaughter, Whitney Gravelle, never met him. But she grew up hearing about his voice.

WHITNEY GRAVELLE: You know, my mom said it used to be like thunder and lightning fighting with one another, and it would be like, boom, boom, boom, back and forth, and then they’d stop, and then drink their coffee and go about their day.

KATZ: Those early morning conversations later became famous in the family, not just because of Abe and his brother’s booming voices, but because of what they talked about.

GRAVELLE: And they would debate over treaty rights. They would debate over history. They would argue with one another, but it was always done out of friendliness. And I remember being told that grandpa would always pull out his copy of the treaty and be like, “Look, brother, this is what it says. This is what we’re entitled to.”

KATZ: Big Abe and his brother were studying their fishing and hunting rights as Ojibwe Native Americans based on a treaty from 1836. And they were starting to fight for those rights, too.

Around this time, in the early 70s, Big Abe helped write telegrams to people like Senator Ted Kennedy and President Richard Nixon, asking the federal government for help. Here are excerpts of what he wrote:

“Dear Mr. President: … the Bay Mills Indian Community and other groups of Indians … depend on fishing as a source of income and their very livelihood. … By the power of the office which you hold, we ask you … to intervene on behalf of our people.”

Big Abe was a commercial fisherman catching the same fish Ojibwe people had caught in Lake Superior for generations. By the mid-1900s, commercial fishing was one of the main ways for Native people to make a living in rural Michigan. Otherwise, tribal members often had to move hundreds of miles away to work in auto plants or factories.

Big Abe needed the U.S. to intervene because the state of Michigan was cracking down on commercial fishermen. The state created new requirements that most bootstrapped tribal commercial fishermen couldn’t meet. These changes suddenly made it nearly impossible for them to fish legally, according to state law.

The thing is, Big Abe and other Anishinaabe fishermen argued that was wrong. That they had the right to fish however they wanted – and the state couldn’t intervene. Their ancestors had signed a treaty with the U.S. government that protected those rights. So they couldn’t meet the state’s requirements, but they still wanted and needed to fish.

JACQUES LEBLANC: Dad used to take us fishing at night. We fished at night.

KATZ: This is Big Abe’s son, Jacques LeBlanc.

JACQUES LEBLANC: That’s the way fishing was done for a Native back then, because we didn’t have a license to fish. … The DNR would be looking for us, and we hid under logs, and we hid behind rocks, and sometimes they’d catch us, sometimes they’d walk right by us.

KATZ: At the same time they were keeping an eye out for DNR officers, non-native anglers were taking things a step further. They believed that Native fishermen were hoarding fish for themselves.

Jacques LeBlanc, one of Big Abe’s children, is still a commercial fisherman. (Credit: Ellie Katz / Points North)

JACQUES LEBLANC: Dealing with racism, we dealt with that every way, shape or form. From our boats getting sunk, to tires being slashed, to sugar in the gas tanks, to shots fired in the air around us.

KATZ: Abe’s daughter-in-law Joann LeBlanc, was around 21 when all this was happening. Her husband Sonny and other fishermen would go fish at night, and she’d go with them. She remembers one night in particular.

JOANN LEBLANC: I can remember sleeping underneath the truck hidden with him. … And then, you know, them going out … there and getting that net.

KATZ: All of a sudden they heard unfamiliar voices from far off.

JOANN LEBLANC: I remember somebody says, “There they are!” Like that. Everybody scattered. And I had a pack of fish on my back … And I threw it around, and it plopped right in front of me. But I ran. I did run. That was scary. I didn’t know what was going to happen.

WHITNEY GRAVELLE: One individual had his boat cut free from the dock as a form of harassment.

KATZ: Abe’s granddaughter, Whitney, again.

GRAVELLE: And he swam out to try and grab it, because when you don’t have a lot of economic means, and that’s your way of life, and that’s how you provide for your family, of course you’re going to try and retrieve it. And he ended up drowning in the water trying to get his boat back. So, like, people were dying as this was happening.

KATZ: By 1971, the entire community was tired of this. An indigenous rights movement was sweeping across the country. They believed they still had a right to fish. They just needed a way to prove it.

GRAVELLE: Someone needed to take a stand, someone needed to defend the treaty right, and then someone needed to affirm it as a way and a means to say, “Hey, not only is this our right, but it’s a protected right, and you can’t do this to us anymore.”

KATZ: Tribal leaders at Bay Mills got together and laid out a strategy: One fisherman would be the guinea pig. He’d turn himself in, get arrested, and take his test case as far as possible in order to get the state courts to recognize treaty rights. Big Abe volunteered.

Big Abe’s wife, Gertrude Amelia “Little Mealie” LeBlanc, at the dedication for the Albert “Big Abe” LeBlanc Building: Chippewa Ottawa Resource Authority building in Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan. (Credit: Whitney Gravelle)

KATZ: Big Abe would later tell a reporter about that day in 1971, quote:

“That September 28, I got into my boat, went out and set some gill nets. I was in Pendills Bay – part of Whitefish Bay – offshore from the reservation, and [I] had a copy of the Treaty of 1836 in my pocket. I just sat there and waited.” Un-quote.

When the DNR officers started arriving, Big Abe came towards shore. His daughter-in-law, Joann, could hear his booming voice as he got closer.

JOANN LEBLANC: Abe was not a man to mix his words or mess with his words: “Those son-of-a-bitches!” You know, I could hear that coming in.

KATZ: When he got on the beach, the officers told him he was under arrest.

Big Abe’s original ticket from the Michigan DNR in 1971. (Credit: Ellie Katz / Points North)

“The hell I am,” Big Abe said. “You can’t arrest me.”

Years later, the Grand Rapids Press reported that he pulled out his copy of the treaty and said, “This treaty gives me the right to fish.”

“We’ll see about that,” an officer said. He didn’t cuff Big Abe and cart him away, but he did confiscate his net and write him a ticket.

That ticket ordered him to appear in local District court for trial in a few days. What happened next, after the break.

(sponsor messages)

KATZ: How far back would you say you have paper copies of everything you’ve worked on?

CANDY TIERNEY: Oh, since the 70s.

KATZ: Oh my gosh, Candy, that’s a lot of paper.

TIERNEY: I know!

KATZ: Candy Tierney’s been a tribal attorney for around 50 years. And she’s got cabinets full of court documents to prove it. When Candy got to Bay Mills in the 70s, she started working on Big Abe’s case: Six-foot-six, 350-pound Big Abe.

TIERNEY: He was driving Cadillacs, and the frame was bent on the driver’s side, so you could definitely see the tilt.

Kathryn “Candy” Tierney holds the ticket Big Abe LeBlanc was issued by conservation officers at Pendills Bay in 1971. Tierney has been a tribal attorney for around 50 years. (Credit: Ellie Katz / Points North)

KATZ: In District court, Big Abe made the same argument he’d been making for years: That his tribe had signed a treaty with the U.S. government in 1836 protecting his right to fish. And the state couldn’t intervene.

The state disagreed. They argued that the Ojibwe and Odawa tribes who signed that treaty gave up those rights in a later treaty. Big Abe went to trial a week after he got his ticket in 1971.

TIERNEY: And the court said, “Everything’s settled. There isn’t any treaty right anymore.”

KATZ: But Big Abe and his lawyers were expecting that. So he appealed that decision. And then he appealed the next decision. And in the years between, he kept fishing. The case went back and forth until eventually, in March 1976, five years after his ticket, his case made it all the way to the Michigan Supreme Court. Candy got to the courthouse early to check things out. And the setup was not gonna cut it.

TIERNEY: ‘Cause they had maybe, like, three pews on each side — looked vaguely church-like, and I knew how many people were coming. I’m saying, “You’re gonna need to bring in chairs.”

KATZ: People started to pour in.

TIERNEY: Most of the entire Bay Mills Indian Community, for one.

KATZ: Plus people from indigenous communities across the state: Keweenaw Bay, Saginaw Chippewa, Grand Traverse, Sault Ste. Marie.

TIERNEY: There was anticipation and pride on the Indian side because, finally, we’re in a court where treaty rights are respected and not considered to be some kind of flaky argument. … And everybody saw this as their fight.

KATZ: Then, you had the state’s side: Tons of people from the DNR and from sport fishermen’s groups.

TIERNEY: It ended up being sort of like going to a wedding: Friends and family of the bride are on one side and the groom on the other.

KATZ: Right behind Candy, in the front row of the audience, sat Big Abe.

TIERNEY: Abey is a big man, and so he was more comfortable in great big T-shirts. And to find a shirt of any kind that would be possible to button or something — it wasn’t necessarily that easy. But he did dress up for that.

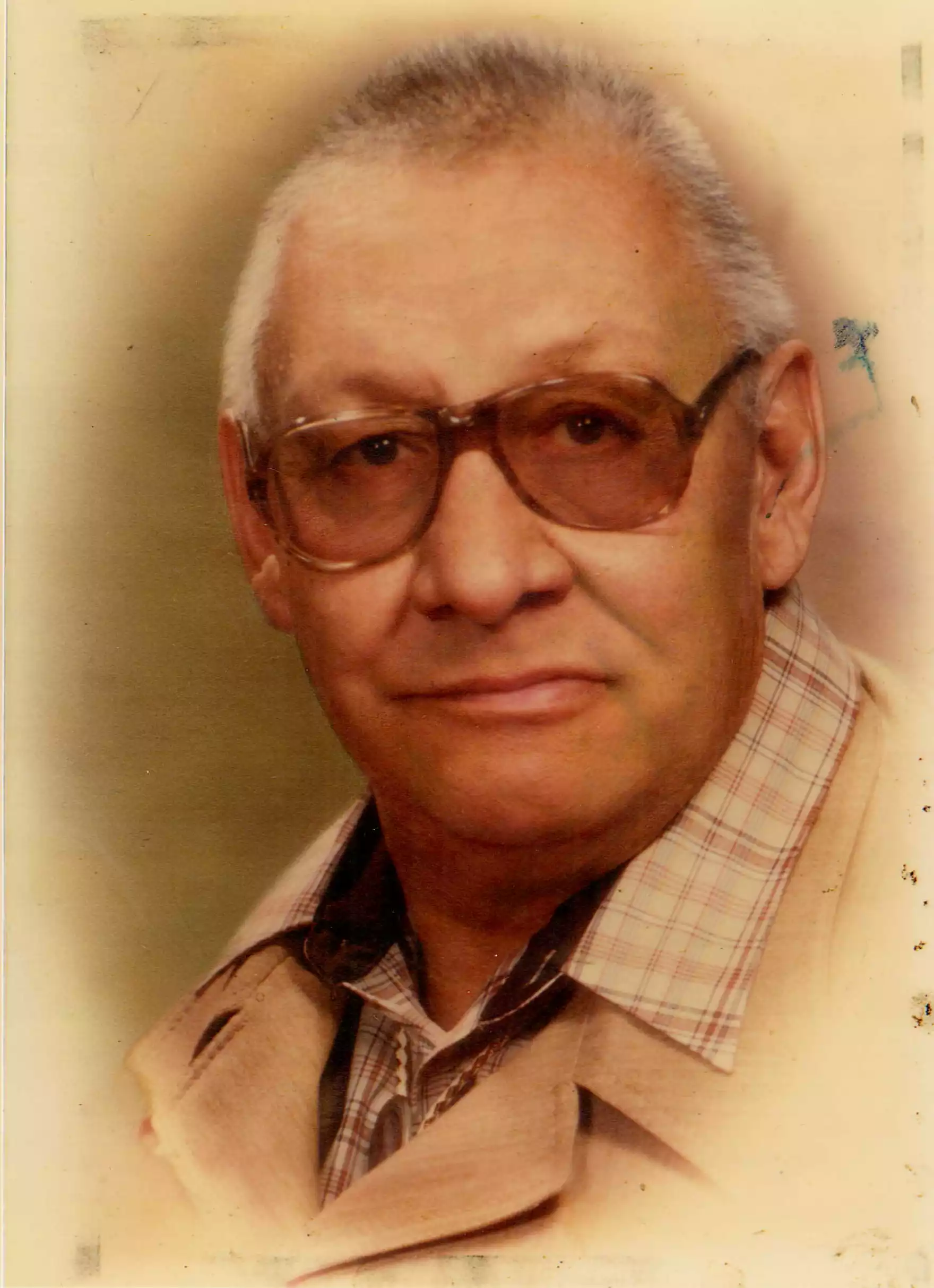

Big Abe LeBlanc (Courtesy: Whitney Gravelle)

KATZ: Each side argued its case. Joann, Big Abe’s daughter-in-law, was there watching Candy make her oral arguments.

JOANN LEBLANC: She was calm, cool and collected. … Like, everybody listening and everything seemed to hinge on her next explanation, or her next word, or how she was going to explain — but it was quiet.

KATZ: The court transcripts from that day have been destroyed.

TIERNEY: I don’t remember exactly what I said. Those kinds of things sort of get kind of vague. … But on this, we were talking about the treaty, the treaty, the treaty, the treaty.

JOANN LEBLANC: I know I kind of felt like standing up and clapping after she was done.

KATZ: After just a few hours in the courtroom, the arguments ended and everybody left. They’d have to wait months before getting an answer.

TIERNEY: We had no idea what the decision was going to be.

… They were pretty sure that their way of life was at risk because, you know, generations back beyond count, people relied upon the resources of the lands and the waters. So in a very real sense, they were fighting to continue to live in the type of communities that they always had and to share the values that were always important. You know, this was their, not only economic survival, but their cultural survival that was at stake. I don’t think I can exaggerate how important this was to people.

KATZ: Six months later, Candy’s phone rang.

TIERNEY: The Supreme Court clerk called … to say that the court had issued its decision. She just said that, you know, they upheld the decision of the Court of Appeals.

KATZ: Once she said that, you knew it was in your favor?

TIERNEY: Oh, yeah.

KATZ: And what went through your head?

TIERNEY: Hot damn. (laughing)

KATZ: Big Abe, and hundreds of other Ojibwe and Odawa fishermen, had the right to fish throughout huge portions of Lake Michigan, Superior and Huron. And in the meantime, another big case was working its way through the legal system.

Remember those telegrams Big Abe sent to Washington, D.C.? The federal government finally stepped up. They sued the state of Michigan on behalf of Bay Mills saying they had the right to fish commercially.

And in 1979, a federal judge in Grand Rapids sided with the tribes. It complemented the Michigan Supreme Court ruling — that treaty rights were officially the law of the land, protecting not only economic survival but cultural survival. It was a sweeping victory for Native American fishing rights in the Great Lakes. Big Abe’s son Jacques was a teenager by this point.

JACQUES LEBLANC: And I remember exactly where I was when it came over the radio.

KATZ: What were you feeling? What did that mean to you?

JACQUES LEBLANC: Well, it was a long battle. … We started fishing in the day more. We weren’t running around at night … we got more and more — more and more advanced with the boats, and the nets, and the trucks and the trailers. Because back when this all started, we hid our boats in the trees, and we drove there in cars. We drove there in vans. We drove there in pickups, and we took our boat out of the trees and went on the lake at night. Now we go out at a boat ramp. That’s the way it changed.

KATZ: Similar legal action swept across the region, in Wisconsin and Minnesota. And the federal case laid the groundwork for how fisheries are managed and regulated in Michigan today — a negotiation between tribal nations, the U.S. government, and the state of Michigan. For Big Abe’s kids and community — that’s part of his legacy.

JACQUES LEBLANC: That he did it for all Natives. He didn’t do it for himself. He wasn’t looking to be the center of attention. … This is, for me, real emotional stuff because it’s my livelihood, and [it’s] going to be till the day I die.

KATZ: Albert B. LeBlanc – Big Abe – died a few years after the federal victory, in January 1983. He was only 59 years old. He was buried in Mission Hill Cemetery in Bay Mills, overlooking Lake Superior.

TIERNEY: When he passed, the tributes were very heartfelt, very eloquent — it was mourning someone who put everything on the line without any guarantee that it was going to be successful.

KATZ: Years later, when a governing body was created to bring all the 1836 tribes together to manage natural resources, the headquarters was named after Big Abe.

TIERNEY: Maybe somebody else would have stood up, but we never would know for sure. So we have our hero, if you will.

Big Abe’s wife, Gertrude Amelia “Little Mealie” LeBlanc, at the dedication for the Albert “Big Abe” LeBlanc Building: Chippewa Ottawa Resource Authority building in Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan. (Credit: Whitney Gravelle)

KATZ: Big Abe’s court victory still lives on today. But there are new things hurting the tribal fishery. And not everybody agrees on what they are.

Some people point to new invasive species like quagga mussels causing another collapse of Great Lakes fisheries. Others say there aren’t enough young tribal members who want to fish as a career. Or that the tribes argue too much amongst themselves about how to allocate fish and fishing grounds. Or that tribes don’t have enough representation. And tribal fishermen still face harassment, especially when they fish in new areas.

In 2023, something happened that at least closed Big Abe’s chapter of the story.

WHITNEY GRAVELLE: So this was the net that my grandpa used when he was out fishing. This is actually old lead weights too.

KATZ: Big Abe’s granddaughter, Whitney Gravelle is now the president of the Bay Mills Indian Community. She opens a box in her office. It’s the net the DNR confiscated that day in 1971.

GRAVELLE: It’s tangled right now, but when we had received it from the state of Michigan, it had essentially been in an evidence locker for over 50 years.

LeBlanc family members with Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer. In 2023, the state of Michigan returned Big Abe’s net to the LeBlanc family after more than 50 years. (Courtesy: Whitney Gravelle)

KATZ: Whitney says it was a little smelly when they first got it back. Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer presented it to the family in a big wooden box. Big Abe’s kids were there, including Jacques, who’s still a commercial fisherman.

JACQUES LEBLANC: Once I heard they were gonna give it to us, I just wanted it. So once the governor presented it to us, I just told my brother, “Grab it. Let’s go.” … But after I got it back home here, and I showed [it to] other people, then I had emotions. And people wanted to touch it, because that’s the net that started at all.

KATZ: What were you feeling here?

JACQUES LEBLANC: Just pride.

KATZ: Joann got a chance to look at it too.

JOANN LEBLANC: My first thing too is I wanted to feel it, and I did just a little bit — but I felt it.

KATZ: What did it feel like?

JOANN LEBLANC: Well, wow, I’m a part of history now, touching this net that made the state acknowledge.

KATZ: Acknowledge that Anishinaabe people always had the right to fish these waters commercially — and they always will.

Attorney Kathryn “Candy” Tierney holds the original brief Big Abe LeBlanc’s legal team submitted to the Michigan Supreme Court. (Photo: Ellie Katz / Points North)

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Points North: Complete With His Language

Points North: A New Hope for Anishinaabemowin

Featured image: Albert “Sonny” LeBlanc, one of Big Abe’s children, holds a 1975 Chicago Sun-Times article about his father. Sonny helped his father set the nets on the day of Big Abe’s citation in 1971. (Credit: Ellie Katz / Points North)