By Michael Livingston, Interlochen Public Radio

Points North is a biweekly podcast about the land, water and inhabitants of the Great Lakes.

This episode was shared here with permission from Interlochen Public Radio.

Microplastics are everywhere. They’re in the air we breathe, the clothes we wear, even the food we eat. Scientists are still trying to understand what these tiny particles are doing to the environment and our bodies.

But an accidental discovery at the University of Michigan in 2019 – involving baby diapers and rubber tires – has broken ground on an idea for how to get them out of our water.

“We just looked at it and I was like, ‘Wow, this is interesting,’ said Takunda Chazovachii, a U of M graduate student at the time. “The conversation was now, ‘What just happened? And let’s try to explain it.’

Research is not a straightforward path though – the idea takes time, money, and repeated failure to research.

Credits:

Producer: Michael Livingston

Host: Dan Wanschura

Editor: Morgan Springer

Additional Editing: Ellie Katz, Ed Ronco, Peter Payette, Dan Wanschura

Music: Blue Dot Sessions

Transcript:

MICHAEL LIVINGSTON, BYLINE: Are they really everywhere?

ANNE MCNEIL: I mean, I would say… yes. They’ve been found everywhere that people have looked for them.

NEWS MONTAGE: The particles come from nearly everything around us.

From the Antarctic to the Arctic.

They pose a particular threat to the oceans and marine life.

They’ve been found in almost every organ in the body. As well as in the bloodstream.

Human fertility and lung function may be harmed.

A potential environmental nightmare.

The problem is not isolated.

DAN WANSCHURA, HOST: Take a look around you. You can’t see them or smell them but tiny pieces of plastic are everywhere. They’re on your clothes, the couch, the car seat. You’re breathing them in and eating them in your food. Yeah they’re small, but many in the scientific community believe they’re a huge problem.

Microplastics: By definition, they’re no bigger than an eraser on a pencil.

MCNEIL: The smallest size is smaller than we can even see with the human eye of like one-seventieth the width of your hair.

WANSCHURA: That’s Anne McNeil, a chemist at the University of Michigan.

MCNEIL: The term microplastic came to be used more widely around the early 2000s when a captain of a boat had noticed all these small plastic fragments floating in the ocean, and he dredged up some just using a fishing net and brought them to shore. And his hypothesis at the time was that, you know, these smaller pieces of plastic are breaking off the larger pieces of plastic, and they really need to be studied separately from the larger plastic waste that we had been studying already.

WANSCHURA: Even though microplastics are everywhere, scientists are still trying to grasp the scope of the problem.

MCNEIL: This is a, like, super active area of research right now asking the question of, “How bad is it for the environment?” I would say any pollutant that we put out there is doing some damage to the environment.

WANSCHURA: And it’s not entirely clear what they’re doing to our bodies. Some newer studies have raised concerns they can kill cells, reduce fertility and be a vehicle for other contaminants.But despite the unknowns, scientists agree that we should work to keep them out of our environment.

Today’s story is about a group of researchers in Michigan who are trying to figure out how to get microplastics out of our tap water.

This is Points North, a podcast about the land, water and inhabitants of the Great Lakes. I’m Dan Wanshura.

The beginning of the story doesn’t actually start with microplastics though – it starts with baby diapers. Michael Livingston takes it from here.

LIVINGSTON: Takunda Chazovachii was a graduate student at the University of Michigan when he made an unconventional discovery. It was 2019, and he was working on a project funded by Proctor and Gamble – the company that makes Pampers. The goal was to find a way to recycle the super absorbent part of the diaper. The part that keeps everything well– contained.

Takunda Chazovachii was a graduate student at the University of Michigan in 2019. (courtesy: Anne McNeil)

CHAZOVACHII: A baby uses six to ten diapers a day in their first year… So, that’s a lot of diapers.

LIVINGSTON: Diapers are made of something called polymers – chemical compounds where molecules link together in long, repeating chains like a zipper. According to one study, approximately 20 billion used diapers end up in landfills each year.

So, Takunda’s hard at work in Ann Arbor, Michigan, trying to figure out how to give diapers a second life. And by using some chemistry, Takunda is able to change the diaper polymers into something entirely new… something sticky. An adhesive. Like something you’d find on sticky notes.

CHAZOVACHII: The bandages that you get in the hospital are based on pressure sensitive adhesives. Tape that’s pressure sensitive adhesive as well.

LIVINGSTON: These adhesives made out of diapers is where the lab’s research with microplastics all stems back to. But it couldn’t have happened without a happy accident. That summer, Takunda takes on an intern – a bright high school student named Edwin Zishiri.

CHAZOVACHII: I’m Zimbabwean. His parents are from Zimbabwe. … That’s how I kind of met, met the family.

LIVINGSTON: It didn’t take long for Takunda to take Edwin under his wing.

CHAZOVACHII: And he’s a very intelligent kid. Actually, when I was working with him … I was on my toes because he was very curious.

Edwin Zishiri was a high school intern at the University of Michigan in 2019. (courtesy: Anne McNeil)

LIVINGSTON: It’s the end of August, Takunda needs to run some tests on his diaper adhesives.

CHAZOVACHII: Edwin was already in the lab when I came in.

LIVINGSTON: Edwin was at their shared station tinkering with tiny shreds of vulcanized rubber from car tires – a new material the lab was trying to recycle. Takunda starts working next to him. As he’s working, Edwin keeps dumping the tire pieces into a clear glass jug between him and Takunda.

Each little black shred is around the width of a human hair. Eventually, he finishes his experiments and takes off for the day. Takunda is the last one in the lab. He looks down at his diaper adhesives.

CHAZOVACHII: They’re just ridiculously sticky.

LIVINGSTON: Almost instinctively, he dumps all those adhesives into the same jug as Edwin’s tire shreds. The solution starts to mix, turning the contents into a deep black– like Dr. Pepper.

CHAZOVACHII: I remember maybe just shaking the container, just interested in that, and shaking the container, and everything was all mixed up.

LIVINGSTON: Takunda cleans his station, packs up for the day, and leaves the jug behind.

CHAZOVACHII: And then I pulled out my funnel and closed it, and then just went, turned off the lights.

LIVINGSTON: The next day. Takunda returns to the lab and finds the mixture in the jug is no longer dark and murky. That surprises him.

CHAZOVACHII: The whole mix is just clear. The whole container is clear. I’m like, what happened?

LIVINGSTON: He immediately gets Edwin.

CHAZOVACHII: I went through the door that goes to the kitchen, and Edwin was sitting in the kitchen. And I said, “Oh, Edwin, let me show you something.

LIVINGSTON: They peer inside the jug.

CHAZOVACHII: And then we see this little blob floating around with all that micronized rubber just, you know, like, adhered onto that little piece of … little blob.

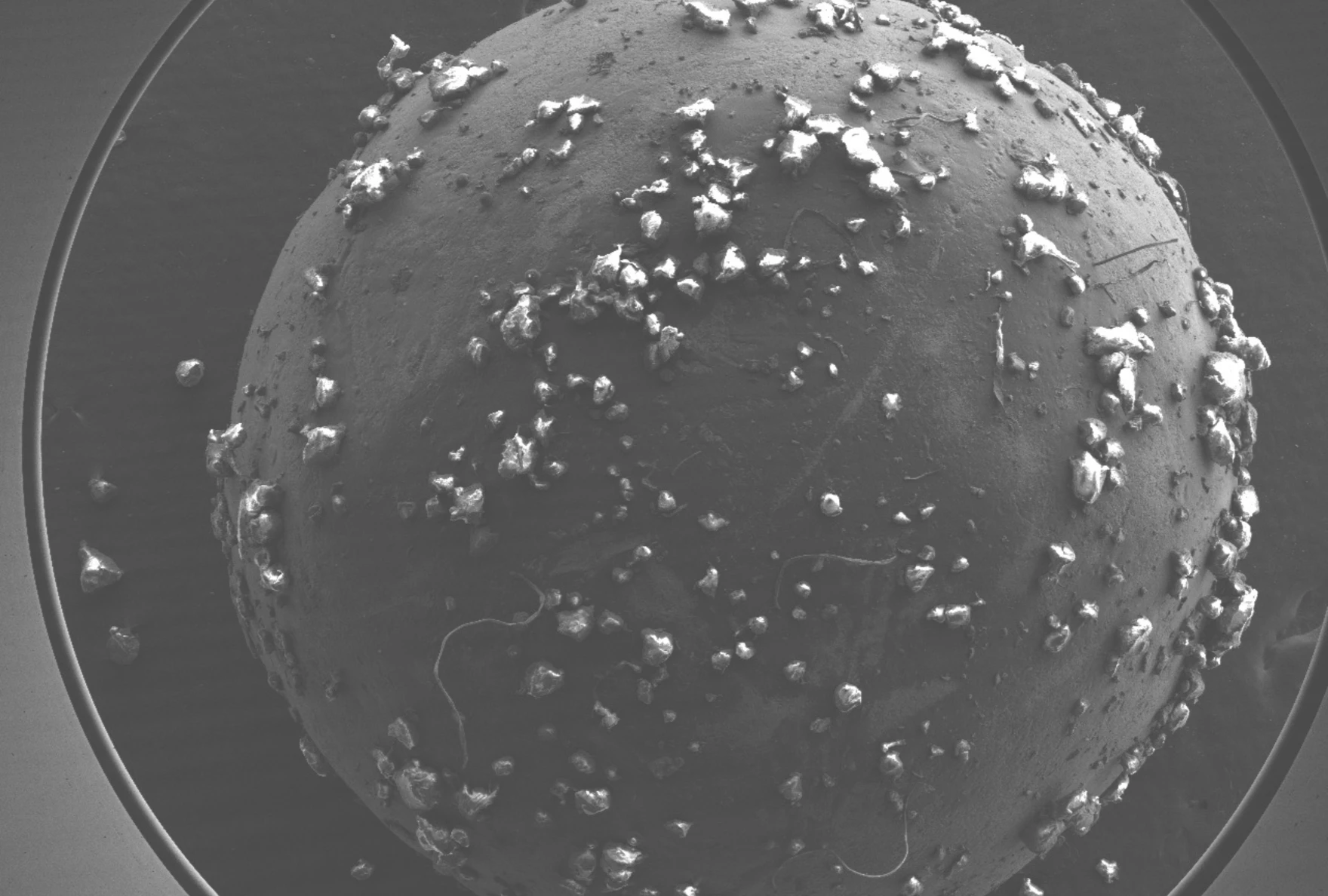

The day after Takunda Chazovachii mixed his adhesives with Edwin Zishiri’s micronized rubber, the adhesives seemed to collect the particles in a “little blob.” (credit: Takunda Chazovachii)

LIVINGSTON: Somehow the adhesives Takunda made from diapers had collected all the black rubber shreds – like a magnet.

CHAZOVACHII: Then we just looked at it and I was like, “Wow, this is interesting.” The conversation was now, “What just happened and let’s try to explain it.”

LIVINGSTON: Takunda whips out his phone and snaps a picture. He has never seen anything like this before. Takunda shows the picture he took of the blob to Dr. Anne McNeil, the chemistry professor we met earlier.

MCNEIL: So, this white part here is the adhesive, and then all the black coating on the top, and the bottom of this white part is the microplastics.

LIVINGSTON: Anne points at her computer screen, she’s kept Takunda’s picture for over five years now. For most of her life, Anne has studied organic chemistry but she says she’s always wanted to find ways to help the planet.

Dr. Anne McNeil is a chemistry professor at the University of Michigan. (courtesy: Anne McNeil)

MCNEIL: From the time I was like a little kid, I had all these save the Earth books in 50 easy steps and stuff like that when I was growing up. And I never quite found the right alignment of my interest in chemistry and my interest in the environment.

LIVINGSTON: Anne’s 47 now. She wears square glasses and has salt and pepper hair. When she sees Takunda’s discovery she immediately lands on an idea: What if his adhesives could capture microplastics in water in our homes?

A single load of laundry releases several million microplastics into wastewater from the washing machine. Anne says it ends up going back to our crops, our sewer systems, eventually our drinking water. It’s just one example of how we’re in a vicious cycle of ingesting plastic waste.

But this idea for a filter would take time, money and repeated failure. That’s after this:

(sponsorship message)

LIVINGSTON: Research can’t happen without funding and meanwhile, the money for Takunda’s work on diaper recycling is running out. But their team of researchers take a hundred-to-one shot at applying for a 2 million-dollar grant from the National Science Foundation. If they get it, they could use the money for more research into how the adhesives could be used to collect microplastics. But Takunda isn’t optimistic.

CHAZOVACHII: There’s a lot of applications in. I would be surprised if we make it to the second round.

LIVINGSTON: While their application goes through, he and Anne begin experimenting – trying to confirm if his diaper adhesives could really capture microplastics in water. The work involves coating different materials with the adhesives and passing a solution tainted with microplastics through them. The prototype experiment involved coating tiny beads with the adhesives.

MCNEIL: Water can flow very quickly, still through there, and it’s a pretty tortuous flow, because they’re hitting beads, and like, they have to get around it. There’s not a single straight path through.

LIVINGSTON: The early results look promising. The adhesives seem to be doing their job – attracting the microplastics to the beads. But the new year comes, and things get difficult. Takunda completes his graduate program and takes a new job as a chemist. The COVID-19 pandemic starts making lab work difficult. But Anne and her team keep working with Takunda’s adhesives. And around this time they discover a huge problem. When they pull the beads out and look at them through a microscope, they discover the adhesives don’t hold up.

MCNEIL: The coatings didn’t look as good– they weren’t as pristine as they did when they went in. … We started to realize that adhesives, especially these types of adhesives, they can move over time.

LIVINGSTON: The adhesives are literally falling off the beads and even shedding into the water, reintroducing some of the microplastics.

MCNEIL: It’s not functioning the way we want, and some of that shedding can also cause it to shed in the water

LIVINGSTON: Do you get disappointed when that happens. Is there ever a sense of like, “Oh, dang, we had it wrong and now we got to do something else?”

MCNEIL: It’s all part of research. Research is defined by its downs, and you can’t let any single down get you down. You have to just figure out what it’s telling you and then improve the design moving forward.

LIVINGSTON: Even though the filter isn’t working after nearly a year of experiments – Anne and her team keep moving. She says science is like a slow moving ball. Sometimes discoveries like Takunda’s make the ball roll faster but it only takes one small set back to take momentum away. The diaper adhesives are going to need more study.

Now it’s the summer of 2020, pandemic lockdowns are still in place but Anne’s interest in microplastics research has only grown. That August, Anne and her team win the 2 million-dollar grant from the National Science Foundation. This is huge and it comes at just the right time. It not only funds the work with adhesives but also helps expand microplastics research across the university.

MCNEIL: We had a good story and a good approach. Fortune lined up for us pretty well on that one.

LIVINGSTON: More of Anne’s students start working on projects to track, map, capture, and remove microplastics from the environment. And they have an idea to get the ball rolling on the adhesives again. Instead of using the adhesives on tiny beads, they start coating sheets of stainless steel mesh with the stuff.

MCNEIL: Almost like a fishing net. If you stuffed the fishing net in there and had it really irregularly, sort of cramped in there, it would allow lots of points of interaction along the way. So, the goal was just increasing surface area.

(sounds of lab)

LIVINGSTON: To get an idea of what these experiments look like, a couple of Anne’s students run a quick test for me.

THURBER: Microplastics are dangerous so we wear glasses, safety glasses and also gloves for these.

LIVINGSTON: That’s Henry Thurber.

RAMKUMAR: What he’s going to show you here now is how the project has improved over time.

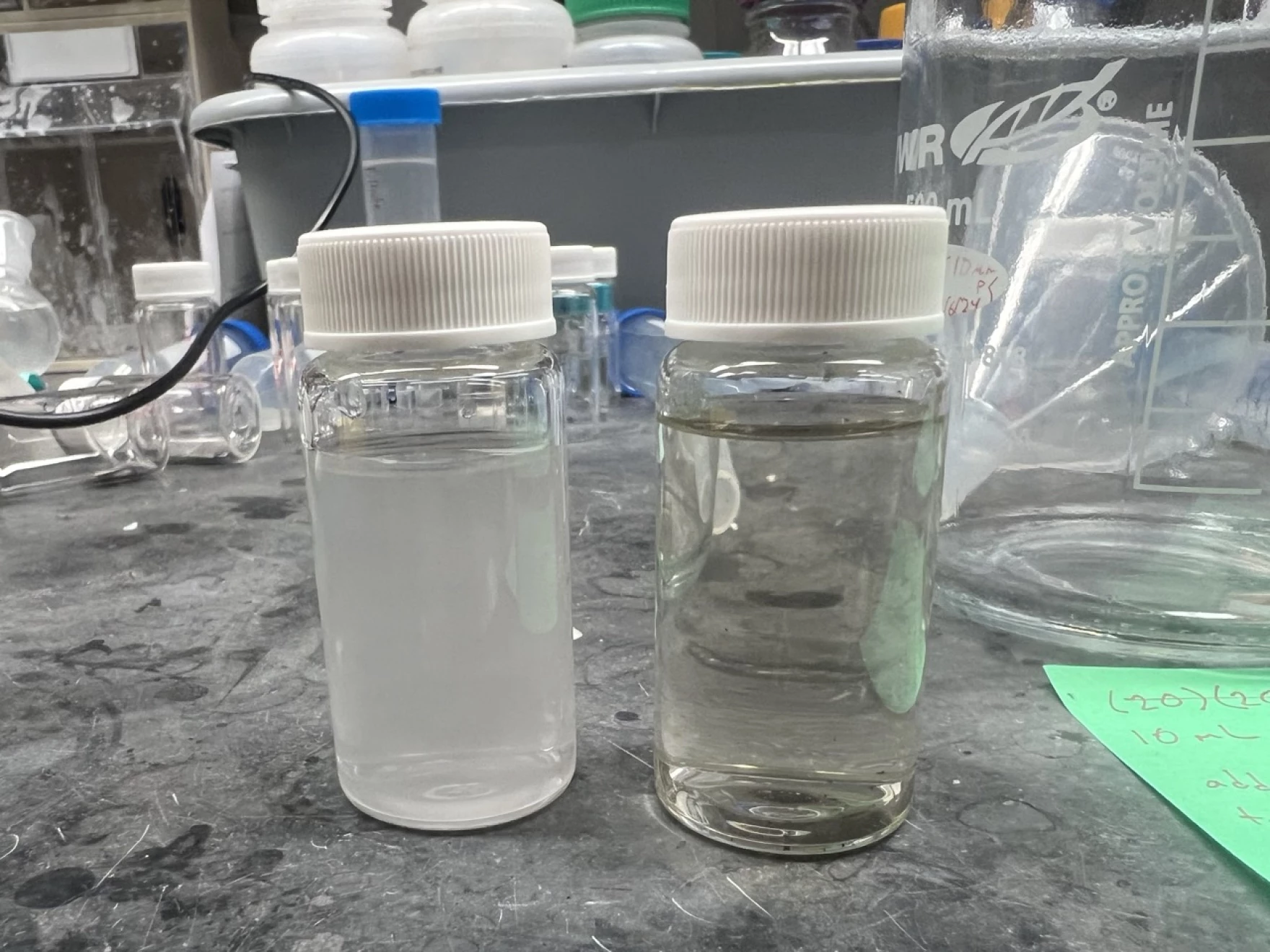

LIVINGSTON: And that’s Malavika Ramkumar. The students set what looks like a cloudy bottle of water on a workstation.

Henry Thurber, a student at the University of Michigan, holds a solution tainted with microplastics before passing it through a filter. (credit: Michael Livingston / Points North)

THURBER: So this contains 10 micron diameter polystyrene beads. So those are micro plastics that you commonly find in the environment.

LIVINGSTON: Henry pours the microplastic solution into a machine that pumps it through a filter.

(sounds of pumping device)

THURBER: Microplastic solution goes through this pump, goes all the way down, and then this water spins up… goes through the stainless steel mesh … and then goes down and circulates through.

LIVINGSTON: Are we going to be able to see anything visually, like a difference in the water? Is it going to be a little clearer?

THURBER: Yes, so I would say in about 10 minutes, we can take the water out, and then you’ll be able to see that it is a lot clearer.

LIVINGSTON: Actually, only about five minutes go by and the water starts changing from cloudy to clear.

LIVINGSTON: I’m already starting to see, yeah, less bubbles.

RAMKUMAR: I mean, the capture rates of this method are pretty high, right? Like, what do you see at 10 minutes?

THURBER: I would say probably 99% of the microplastics are captured in nine or in 10 minutes, probably 90% in two and a half minutes.

LIVINGSTON: 99% of microplastics – captured in a matter of minutes. And Henry says all this equipment is perfectly suited for the home.

THURBER: Using that recycled adhesive for microplastics– so, that’s fairly cheap. The stainless steel we’re coating it on very commercially available, which is also great. And then this spin down setup itself would only cost, like $20 or $30 on Amazon.

A solution tainted with microplastics before (left) and after (right) passing it through a prototype filter. (credit: Michael Livingston / Points North)

LIVINGSTON: This is a huge step toward a final product for Anne’s lab. Now, they can start testing less concentrated microplastics solutions – something closer to drinking water.

MCNEIL: Yes, we can reliably count like 15 particles per liter, and then we can show with the mesh that we could remove those particles quantitatively like, that was a pretty cool day. … I get to experience those joys with them.

LIVINGSTON: It’s 2024 now, and the microplastics filter seems closer to reality than ever – if not for one familiar problem that keeps haunting them. Even when using a stainless steel mesh, Anne believes the adhesives could still be shedding.

MCNEIL: It’s just like when you paint your car or you paint your house or whatever, or window frames, like you can physically break off some of the coating because it’s not chemically bonded. It’s just another layer on top of that layer. That’s one of the limitations that we’re working on now. That is honestly the biggest limitation of that.

LIVINGSTON: It’s the big setback with this project. If the adhesives flake off the mesh, it poses the risk of putting microplastics back into the water. Bottom line: the diaper adhesives aren’t perfect.

LIVINGSTON: Do you often feel like you’re chasing perfection? Is that sort of a quality of science?

MCNEIL: That’s definitely, I would say, one of my biggest struggles in this area, and maybe in science in general, is knowing when to stop, or knowing when to say, “It’s good enough. Now move to this other thing.”

LIVINGSTON: But Anne says she’s not moving on when it comes to the idea of a microplastics filter. Her team is going to keep trying to find a way to make them a reality. She says there’s a need for these devices. Filters specifically targeting microplastics can only be a net positive for keeping them out of our bodies and the environment.

Most home filters out there don’t specifically target microplastics. And no filter has ever used adhesives to do it. Anne is so hopeful she’s going to find a solution using these adhesives, that she’s patenting the idea. And she’s in talks with a business partner about eventually getting them out on the market, when that day comes.

LIVINGSTON: You’re putting in work to innovate and come up with solutions that all of us can benefit from, right? What motivates you in that work?… With science being such a slow process and such a slow moving ball to come into the lab every day and get it done?

MCNEIL: If our work can help in any way, that gives us all the hope we need to get out of bed each day and come in and work on the problem. We know what the challenges are in front of us, and if we can make that small little nudge forward that’s worth getting up for in coming into lab.

LIVINGSTON: More than five years later, Anne is still grateful for Takunda’s happy accident. Without it, she wouldn’t be so close to breakthroughs in microplastics research. For her team, getting microplastics out of water is a problem that can be solved, and it doesn’t matter how many setbacks it will take to figure it out.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Points North: The Squeaky Sand Phenomenon

Points North: Complete With His Language

Featured image: Microplastic particles stick to a molecular sieve bead covered with adhesives derived from diapers. (credit: Violet Sheffey-Chazovachii)