By Rambo Talabong, Inside Climate News

This article originally appeared on Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, non-partisan news organization that covers climate, energy and the environment. Sign up for their newsletter here.

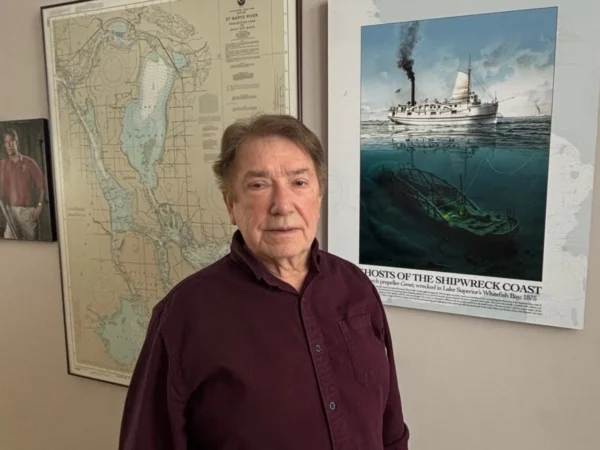

MANHEIM, Pennsylvania — Stephen Haldeman has four apps on his phone just to check air quality, and they have become part of his morning routine: a shot of hot coffee in his favorite white mug, his seat by the sunlit kitchen window and some quick research on his phone that will decide if he can go out that day.

“I wish I wouldn’t have to do it. But for me, unfortunately, when the air is bad, my throat goes tight. My eyes water. Suzy gets headaches,” Haldeman said, referring to his wife, Suzy Hamme.

Retired and in their 70s, Haldeman and Hamme can’t afford to take chances. They’re both sensitive to pollution and doctors recently found a lump in Haldeman’s right lung that restricts his breathing.

Haldeman’s apps include the EPA’s own AirNow, as well as the independently run Purple Air, which collects data from low-cost sensors purchased and installed by users of the app, one of which is hanging by the shed in their backyard in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania.

“The federal one, the AirNow app, is never as precise as our Purple Air monitor here,” Haldeman said, noting that AirNow frequently underreports the pollution in their area. “I think it’s because, on their own, they have so few testing stations and the one that’s closest to us is 10 miles away.”

Haldeman’s hunch aligns with a troubling reality. According to new research from the University of California, Berkeley, more than 20 million people live in urban neighborhoods across the U.S. that are air-quality “blind spots”—areas experiencing dangerous levels of soot pollution subject to the government’s standard but don’t have enough government sensors to flag it.

These blind spots comprise 44 percent of all urban areas in the U.S. that are projected to have hazardous air pollution.

“There are around 1,000 regulatory monitors in the U.S., but it’s far from enough,” said Yuzhou Wang, a postdoctoral fellow in environmental engineering at Berkeley and the chief author of the new assessment. Wang, who grew up experiencing thick smog in China, mapped the blind spots with the help of data from satellites, including traffic corridors and locations of pollution sources like factories.

Lancaster is a particularly egregious example, Wang said. Based on her model, there are at least nine census tracts in Lancaster beyond the reach of government sensors. That includes Manheim, the borough where Haldeman and Hamme live.

However, apart from environmentalists like Stephen Haldeman and Suzy Hamme, air quality is an issue that many in Lancaster County tend to overlook, says County Commissioner Alice Yoder.

“It’s been very difficult because there’s just been no other data and no one that actually sees the poor air quality,” Yoder said. “And so that’s making it difficult for people to want to take action and do something about it.”

Lancaster’s looks deceive, with its bucolic patchwork of green pastures, golden cornfields and winding country roads with occasional Amish buggies chugging by. But its beauty masks an invisible problem: its air is the 30th-worst in the U.S. for short-term particle exposure, according to the American Lung Association. Small particles are a major health risk because they can penetrate deep into the lungs and are linked to a host of complications, including heart and lung diseases, cancer and a higher overall risk of premature death.

Lancaster is currently listed as out of compliance with federal standards for ozone smog but in compliance for particle pollution. Local environmentalists, though, are skeptical and want the state to install additional sensors to allow for a more accurate assessment.

Without precise monitoring, tracing air pollution to its source in Lancaster turns to a guessing game. Haldeman and Hamme believe a huge part of it is their area’s constant traffic of cars. Some Lancastrians blame agricultural processing on nearby farms. Others suspect burning of trash in remote communities.

Sean Nolan, head of the air monitoring division at the state Department of Environmental Protection, thinks all the suspicions of Lancastrians are right on the money.

“It’s a combination of everything that we’re seeing,” he said. Asked if they have a picture of how much of the air pollution pie is divided, Nolan said his department is still in the process of preparing the report.

Aside from Lancaster, other air pollution blind spots across the U.S. include the outer urban areas of Cleveland, Dallas, Milwaukee and San Luis Obispo, California.

Adding demographic data to its model, Wang’s team found that people of color and low-income populations are disproportionately affected. People of color comprise 50 percent of those living in blind spots, double their 25 percent share of the U.S. population.

The Biden administration is aware of the problem. As it moved to set stricter standards for small particles and other pollutants, it also earmarked tens of millions of dollars to expand the air sensor grid through the Inflation Reduction Act, inviting local governments and nonprofits to propose new ways to monitor air pollution. The state of Pennsylvania bagged more than $800,000, but Lancaster is not listed as an area that will benefit, according to the grant announcement.

Meanwhile, Pennsylvania’s draft plan for air quality monitoring in 2025 does not include any additional sensors for Lancaster. Instead, the state plans to install them in counties that suffered heavily when smoke descended south from the 2023 wildfires in Canada.

Asked why Lancaster does not have more government sensors, Nolan said it’s because Lancaster, with two sensors, technically meets the EPA’s “minimum requirements.” So, on paper, there is no lack of sensors.

How about requirements reported by communities?

“Unfortunately, we are unable to exactly monitor where some of these ‘hot spots’ are occurring, at least according to the data analysis that was completed as part of the study,” Nolan said. “I think that this is where additional technologies can come into play. Where we have low-cost sensors.”

Nolan added that as much as Pennsylvania would like to add sensors to Lancaster’s outer communities, it is constrained by siting requirements. Sensors “have to be a certain distance from trees and a certain distance from roadways,” Nolan explained. “That is a long process to determine, work out land agreements, and set everything up associated with being able to monitor in a particular area.”

The inadequate government monitoring is what pushed people such as Haldeman and Hamme to take matters into their own hands by purchasing their own pollution monitors through their local Sierra Club.

Air quality monitors like this one are usually hung high in backyards and garages to get a clear reading of the air. Credit: Rambo Talabong/Inside Climate News

But community-run sensors can only do so much. While the Purple Air monitors can be purchased for as little as $250 each, the much more capable government monitors—which cost at least $20,000, not including upkeep—provide higher accuracy and legal authority. Nolan said these official sensors are finely tuned to meet federal standards, ensuring their readings are admissible in court or administrative proceedings.

“The EPA wants to rely on 100 percent robust data. They have a very high standard for the data that they use when they make some decisions,” Wang said.

Recognizing the need to fill in the air monitoring gaps, the EPA in 2022 included Purple Air monitors in its reporting of air pollution, calling them “supplemental” to the government-run grid. In the end, however, the commercial sensors can’t influence government decisions on whether to impose stricter anti-pollution rules on a community, such as requiring more mass transit.

“Low-cost sensors do not trigger such a process,” said Priyanka deSouza, an air policy researcher at the University of Colorado Denver. “That is why many researchers still think that regulatory monitors have a very, very important role to play.”

In their paper, Wang and her co-authors urge the U.S. to prioritize placing new government sensors in blind spots with the highest populations. Improving coverage in the ten most populous blind spots would reduce the number of people affected from 2.2 million to 900,000, according to their projections.

Until the situation changes, locals such as Haldeman will have to continue to rely on backyard sensors and phone apps—tools whose readings, though useful, fall short of compelling action from state officials.

“The one thing that I counted on the government for, the federal government, even the state government at some point, is to protect me,” he said.

He remembered how inspired he felt in the 1970s, when Congress passed major environmental laws like the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act. Now, he said, Lancaster’s ongoing air-pollution problems feel like a broken promise.

“I thought we were making some headway here,” he said. “And it looks like we’re going into another stinky cycle.”

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Inside is Not the Answer: Air quality in the Great Lakes

Expecting smoke to be a more frequent part of seasonal planning

Featured image: Lancaster County residents Suzy Hamme and Stephen Haldeman bought their own air quality sensor, as government pollution monitoring is inadequate in the region. Credit: Rambo Talabong/Inside Climate News