By Kelly House and Aaron Martin

The Great Lakes News Collaborative includes Bridge Michigan; Circle of Blue; Great Lakes Now at Detroit PBS; Michigan Public, Michigan’s NPR News Leader; and who work together to bring audiences news and information about the impact of climate change, pollution, and aging infrastructure on the Great Lakes and drinking water. This independent journalism is supported by the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation. Find all the work HERE.

Fathoms beneath present-day Lake Huron, early Americans once stood on dry land, hunting caribou as the animals migrated between southern Ontario and northeastern lower Michigan.

A team led by University of Michigan researchers drew international attention when they announced those findings a decade ago, after discovering rock arrangements indicative of prehistoric hunting camps on a lake bottom ridge.

But far less fanfare has followed the scientists in years since, as they’ve pieced together an increasingly clear picture of life 10,000 years ago in the now-submerged subarctic grassland.

“The thing that’s difficult with this kind of research — and it’s difficult for donors and everyone else to understand — is that it’s a real drudging process,” said John O’Shea, a U-M archaeologist and lead researcher on the project. “You don’t just go out and discover a pyramid, right?”

But gradually, they’ve collected evidence amounting to “an incredible picture that was totally unimagined before we started doing this work.”

They’ve discovered fragments of tools that look nothing like other Great Lakes artifacts from a similar time period. They’ve found ancient trees — roots still intact — at the bottom of the lake. They located peat bogs where seeds have been preserved by the lake’s cold, fresh water.

And importantly, they’ve developed a template for doing prehistoric research underwater — one that will soon be put to use elsewhere in the Great Lakes.

“We’re developing brand new methods to do archaeology that no one’s ever done before,” said Ashley Lemke, a University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee professor who began studying the Lake Huron site when she was a graduate student.

But with funding for the project soon expiring, O’Shea and his collaborators fear they could be forced to halt investigations into Michigan’s submerged society before they’ve uncovered all of its secrets.

A ‘Pompeii-like’ discovery

For a century or more before the U-M team’s discovery, people had speculated about ancient civilizations beneath the Great Lakes.

But those hypotheses were never vetted. Scientists figured in the millennia since higher water levels created present-day Lake Huron, all evidence would have decayed away or become buried under sand.

“What we’ve actually proven is that none of that’s true,” O’Shea said.

Instead, frigid temperatures and pristine water safeguarded objects left behind by inhabitants of the Alpena-Amberly Ridge, a geological formation that connected the present-day northern Lower Peninsula to southern Ontario until about 8,000 years ago.

“We believed that it preserved the kind of ice-age like environment that was attractive to animals like caribou,” O’Shea said. Because humans would have hunted caribou for food, “that attracted our interest as a potential site for early human occupation.”

O’Shea’s team began exploring the ridge in 2008, using sonar, remote-operated vehicles and eventually human divers. They found stone hunting blinds, a boulder pathway used to herd caribou toward waiting hunters, and stone flakes leftover from spear point repair projects.

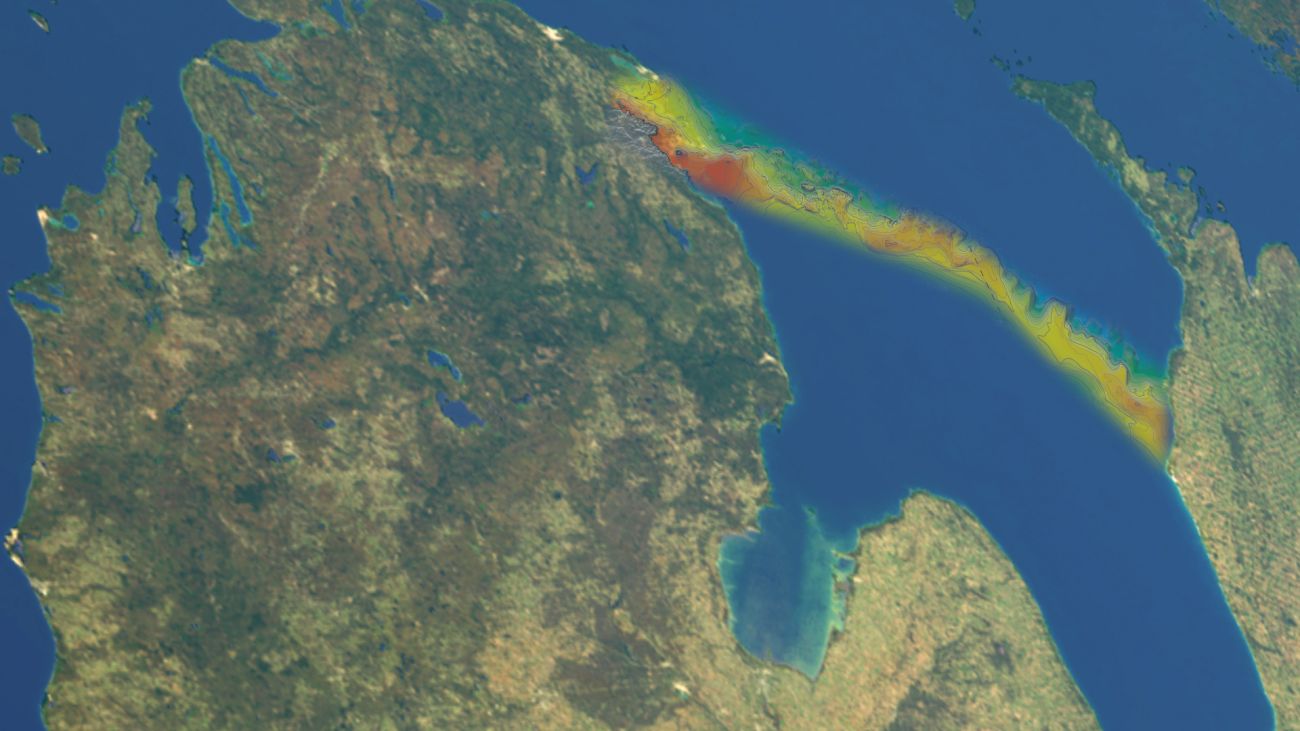

A graphic illustration shows the stretch of land between southern Ontario and northeastern lower Michigan called the Alpena-Amberley Ridge. (Image courtesy of Aaron Martin)

The scene was “Pompeii-like,” in that it hadn’t been moved or destroyed for thousands of years, said Lemke. “In the Great Lakes, it’s the oldest thing that’s ever been found.”

The initial discovery prompted a flurry of attention, including profiles from National Geographic and the New York Times.

In the years since, the team has quietly kept seeking — and finding — more evidence. That includes small tools that look nothing like the large spear points archaeologists typically find at Great Lakes sites from the same time period.

The distinction begs questions: Who were these early Americans, and why do key aspects of their lives seem so different from those of their contemporaries?

“We’re trying to understand who they are, where they came from, what this technology is, and then what happens to it after all this goes underwater,” Lemke said.

Submerged beds of 9,500-year-old peat could contain some clues. Researchers have also found flakes of volcanic obsidian from central Oregon, indicating early Great Lakes residents had contact with their contemporaries thousands of miles to the west.

And the peat is laden with pine needles, seeds, leaves and other preserved matter from which researchers hope to piece together a clearer picture of our region’s distant past. Such well-preserved sites are rare on land, where decomposition is hastened by acidic soil teeming with microorganisms.

The Great Lakes researchers are now collaborating with a lab in Cambridge, England to extract DNA. The results could be “transformative,” O’Shea said.

“It will literally be the first time we have positive evidence of what animals were there,” he said.

By O’Shea’s estimate, there are years more research left to do. But funding dries up after this summer. The team has applied for a three-year federal grant to continue their work. If it doesn’t come through?

“When we stop, the work is going to stop,” O’Shea said.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Strong winds uncover spectacular features and long-lost structures

Tracing for human remains on shipwrecks with environmental DNA

Featured image: A diver looks at a piece of wood discovered at the bottom of Lake Huron where frigid temperatures and pristine water safeguarded objects left behind by inhabitants of the Alpena-Amberly Ridge. (Image courtesy of Aaron Martin)