“Nibi Chronicles,” a monthly Great Lakes Now feature, is written by Staci Lola Drouillard. A Grand Portage Ojibwe direct descendant, she lives in Grand Marais on Minnesota’s North Shore of Lake Superior. Her nonfiction books “Walking the Old Road: A People’s History of Chippewa City and the Grand Marais Anishinaabe” and “Seven Aunts” were published 2019 and 2022, and the children’s story “A Family Tree” in 2024. “Nibi” is a word for water in Ojibwemowin, and these features explore the intersection of Indigenous history and culture in the modern-day Great Lakes region.

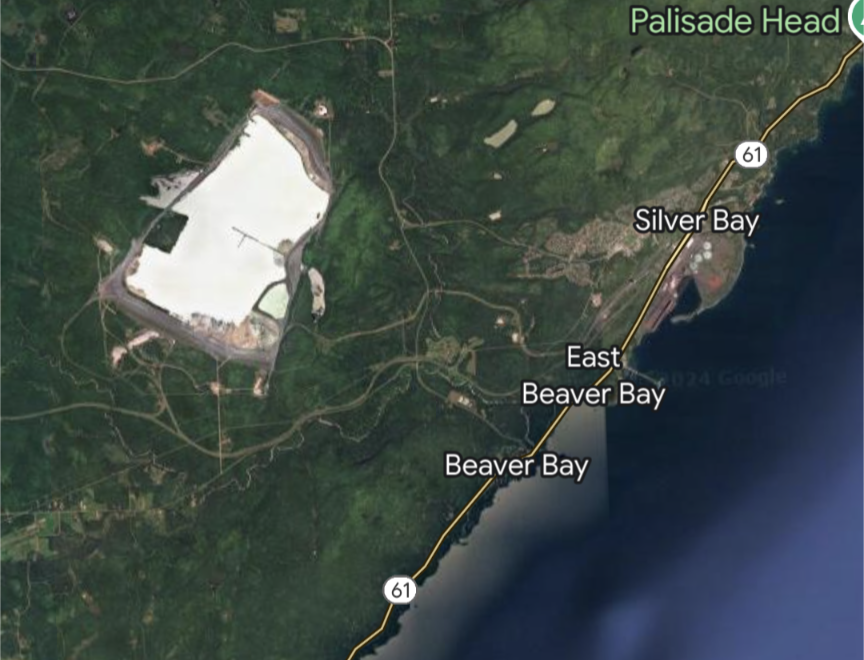

In April, Paula Maccabee, an attorney for WaterLegacy, filed a lawsuit against the mining company Cleveland-Cliffs, regarding their iron ore processing facility Northshore Mining. The lawsuit was prompted by the company’s plan to expand their tailings storage basin at Mile Post 7 in Silver Bay, Minnesota, and the decision not to pursue a full environmental review.

The expansion includes relocating a railroad, building upstream dams and managing stream mitigation adjacent to the tailings basin, which is located 600 feet above Lake Superior and only three miles away. After receiving over 1,300 public comments, including formal comments from Tribal agencies, the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (DNR) announced it would not do a deeper environmental assessment for the expansion, arguing that the 1977 master permit and an Environmental Assessment Worksheet (EAW) released in 2023, provided enough data to move forward.

At a court hearing on November 13, Maccabee made the case for a new Environmental Impact Statement (EIS), based on the company’s proposal to accommodate six times more taconite waste at the site. The last EIS was done in 1976, after Reserve Mining (the company that owned the plant at the time) and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) settled a lawsuit that required the company to relocate their waste tailings. Tailings mainly consist of crushed rock and water — it’s essentially all of what’s left after the target mineral is extracted from the ore, which also includes other trace metals and additives that are used in processing (i.e. cyanide, petroleum byproducts and sulfuric acid).

Paula Maccabee and members of the public at the November 13 hearing. (Photo courtesy of Sophia Patane)

Since the master permit for the tailings basin was issued in 1977, the slurry of fine taconite tailings (small or fine particles of waste), course tailings (large particles of waste) and wastewater has now grown to 2,100 acres — and the company wants to increase storage at the site. According to WaterLegacy, the proportion of polluted wastewater at Mile Post 7 is close to the breaking point, due to 45 years of perpetual use, and the liquification of course tailings into fine tailings. This growing layer of sediment at the bottom of the basin has created unstable conditions, especially considering the company’s request to make the basin taller and add upstream dams. Maccabee compares the expansion to a bread-bowl lunch, with “too much soup and not enough bread.”

A Time Before Environmental Regulation

The story of taconite processing on the North Shore goes back to 1947, with the first permit to mine. The town of Silver Bay sprung up in 1956 when Reserve Mining built the first taconite processing plant in North America.

Located on Lake Superior, the plant employed 2,500 workers and the town grew to 5,000 people. For every ton of taconite pellets produced, two tons of tailings are generated as biproduct, due to the large amount of water required to process raw ore into a pure form. These tailings were funneled directly into Lake Superior at the rate of over 60,000 tons per day — the equivalent of one railroad car every two minutes.

This practice continued unimpeded by environmental regulations until the mid-1960s, when people on Wisconsin’s South Shore, and citizens in Duluth began to voice their concerns about water quality. Fishermen noted fewer herring and water clarity was reduced from 35-40 feet, to five feet in areas affected by the “green fog” of tailings pollution.

In 1972, when asbestos was discovered in Duluth’s water supply, the EPA sued Reserve Mining for a violation of environmental laws and ordered the company to find another place to dispose of the tailings. After six years in appeals court, a new site was established in 1980, which was based on the 1976 EIS. The original 1985 Permit to Mine has since expired.

A 28 Foot-High Wall of Water, Moving at 20 mph

The Grand Portage Band of Ojibwe was one of the agencies to request a compulsory EIS to evaluate the accumulative impact of the proposed project. In a letter sent to the Minnesota DNR on May 18, 2023, Grand Portage stated that: “Mile Post 7 has been allowed to operate for 40 years without permits that require compliance with current statutes and rules. Therefore, the MDNR must now compel Cleveland-Cliffs to apply for new permits that comply with dam safety statutes and state water quality standards.”

Aerial map of Mile Post 7. (Photo courtesy of WaterLegacy)

As Grand Portage wrote in their letter, Cleveland-Cliffs has never applied for a dam safety permit. The company and the DNR assert that the “basin dams are subject to extensive regulatory oversight pursuant to the DNR’s Master Permit.” Grand Portage also requested that the DNR “must require Cliffs to have enough financial assurance set aside to protect reserved Tribal resources, the surrounding community, the environment, and taxpayers from tailings dam failure and tailings basin pollution.”

The Band points out that the company has already made unapproved changes outside of the original master permit. Citing a July 28, 1993 event in which a 27-acre coal ash heap containing approximately 770,000 cubic yards catastrophically failed, sending mercury-laden waste across Highway 61 (the only direct route connecting towns along the North Shore of Lake Superior), and depositing the contaminated slurry into the Beaver River and Lake Superior.

Cleanup of the slump cost the company $11 million, and according to Grand Portage, water resources have not been fully restored. After the collapse, the coal ash disposal pond was relocated inland next to the current Mile Post 7 tailings basin, where it remains today. This change, among others, was not addressed in prior permits.

One of the uncontested data points from the original EIS concludes that a catastrophic failure for any reason at Mile Post 7 would be a lot worse than the coal ash spill. As stated in the document, “a 1,000-foot breach in the 13,000-foot, south dam at Mile Post 7 would produce a 28-foot-high wall of water moving down the Beaver River valley at more than 20 miles per hour to Lake Superior.”

In other words, should the south dam fail, a 28-foot-tall mountain of polluted water would cascade downhill, directly into Lake Superior, destroying everything in its path. One of the irrefutable facts about building wastewater basins like the one at Mile Post 7, is that even if after mining ends, the abject threat to Lake Superior does not end. It is part of the so-called legacy of mining on the Great Lakes.

Redacted Reports Sent to Tribal Agencies

Another concern are changes to the environment that were not present 45 years ago. As Maccabee stated at the hearing: “There was no study at all in 1975 of the impacts of climate change. And now it’s uncontroverted that there are extreme weather events as a result of climate change.”

One such uncontroverted event occurred in June, 2024 when a storm dumped 4-8 inches of rain across northern Minnesota. Highway 61 washed out in several places and water levels grew exponentially in the span of a few hours. If rivers can overflow their banks, it’s easy to see how the dams at Mile Post 7 could be tested beyond their limits by repeated and prolonged extreme weather events.

In their comments to the DNR, Grand Portage confirmed that they, Fond du Lac, Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission (GLFIWC) and the 1854 Treaty Authority staff requested dam safety inspection documents from the Minnesota DNR in 2021 to assess permitting needs for the project. More than one year later, the agencies did receive most of the documents, but they were heavily redacted.

As the Band pointed out:

“The redactions included all identified seepage locations and their discharge rates and any information regarding potential dam failure or identification of vulnerabilities that could cause a dam breach.” Adding that, “Tribes are governmental agencies that co-regulate activities that can impact reserved resources within the 1854 Ceded Territory, and we do not represent the public; therefore, these redactions should not have occurred.”

Grand Portage Water Quality Specialist, Margaret Watkins, confirmed that to date, neither Cliffs nor the DNR have complied with the Band’s request for unredacted reporting.

In their summary, Grand Portage states that:

“The potential for and the impacts of a dam breach or catastrophic failure on treaty-reserved natural resources, the surrounding communities, nearby streams, and Lake Superior must be assessed. The EIS must also evaluate and assess all the Mile Post 7 tailings dam features, including the coal ash pond and other structures and construction methods that have not previously undergone full environmental review.”

At the recent hearing, Oliver Larson, legal counsel for the DNR, argued that an EIS “would not change the catastrophic, potential outcome, should a dam fail,” asserting that there was enough environmental information gathered in the 1977 Master Permit and subsequent environmental study, as required by the statutory framework.

While hearing testimony, one of the justices stated that, “while everyone including the DNR agrees that a dam failure would be catastrophic, the project is changing and along with that, the risks also change.”

The MN Supreme Court is scheduled to deliver their opinion in 90 days. Public comments to the DNR about the project may be sent to environmentalrev.dnr@state.mn.us. You can also find more information about this and other current and proposed mining projects at waterlegacy.org.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Nibi Chronicles: Manoomin as medicine

Nibi Chronicles: The Gift of Manoomin

Featured image: View of Mile Post 7. (Photo courtesy of Save Our Sky Blue Waters)