Spooky Lakes: 25 Strange and Mysterious Lakes That Dot Our Planet is a new book by Geo Rutherford. Below is an adapted excerpt from her New York Times best seller, all about Lake Superior. Follow Geo on TikTok or Instagram for more content on spooky lakes.

Spooky Lakes: 25 Strange and Mysterious Lakes That Dot Our Planet is a new book by Geo Rutherford. Below is an adapted excerpt from her New York Times best seller, all about Lake Superior. Follow Geo on TikTok or Instagram for more content on spooky lakes.

Chock-full of shipwrecks, Lake Superior is a graveyard for thousands of people who have perished there. There is a rich and intricate history of ships navigating the Great Lakes’ vast waters because they serve as a vital shipping highway through the Eastern North American continent, from the Atlantic Ocean to Lake Superior. However, the sheer scale of Lake Superior means it can be incredibly dangerous, and on windy days waves can reach up to 29 feet high. That’s taller than a two-story house! During storms, these massive waves can engulf ships, dragging them down to a watery tomb.

The largest lake in North America, Lake Superior is so big that sometimes people refer to it as an inland sea. It would take four to five days to drive around the perimeter and over two days to walk across the lake from Marquette, Michigan, to Terrace Bay, Ontario (assuming you could walk on water). On average, the lake is around 500 feet deep, which is deeper than most lakes in the world, but at its deepest point, it stretches to 1,332 feet below the surface. There is so much water in Lake Superior that it holds 10% of all available unfrozen fresh water in the world.

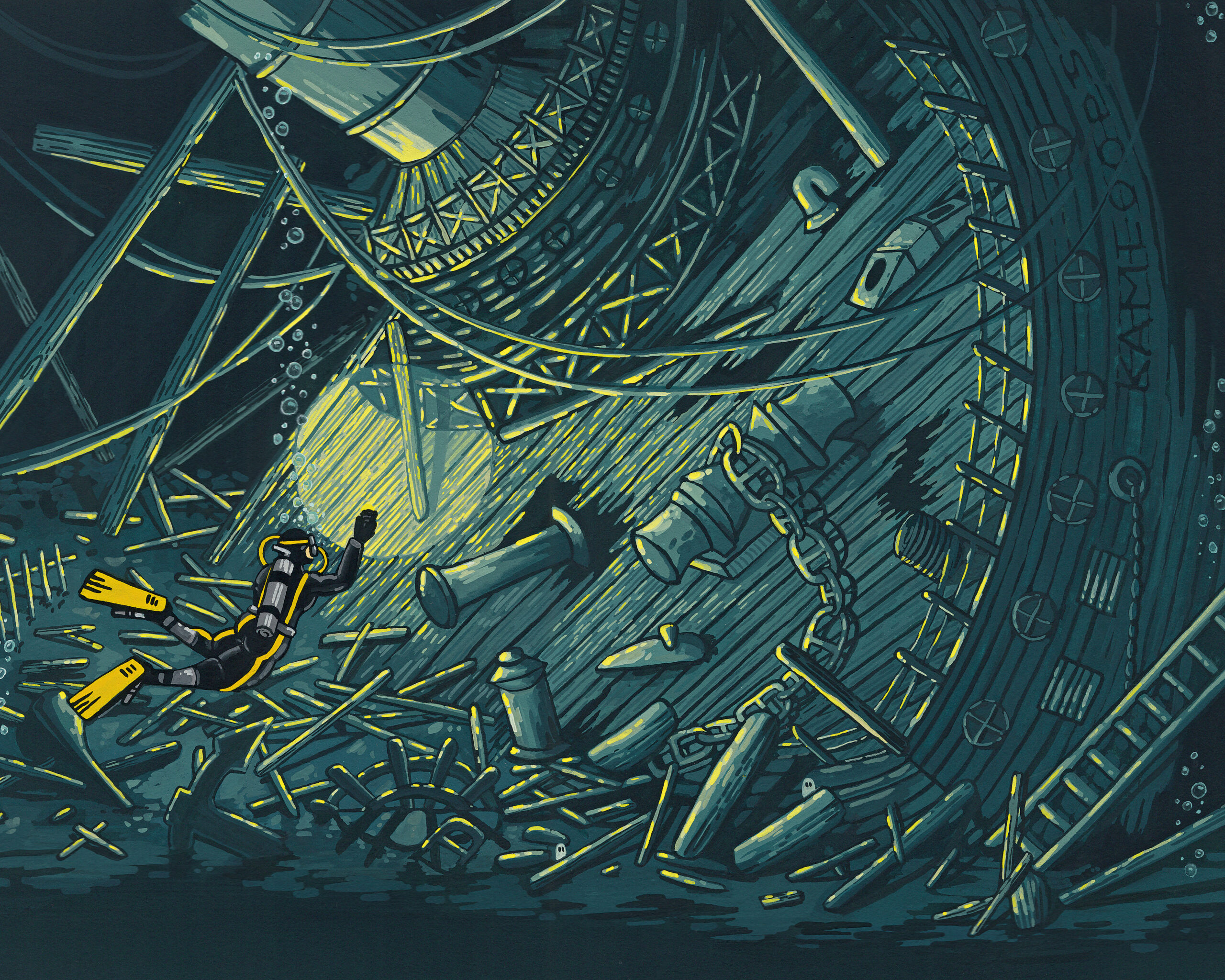

Many of the shipwrecks in Lake Superior have never been found: lost pieces of history, frozen in time at the bottom of the lake. Some of the known locations are open to divers, but when the ships contain human bodies, they are considered graveyards and can be off-limits. One such site is the Edmund Fitzgerald, lost in the storm of 1975 and arguably the most famous shipwreck of the Great Lakes. The crew of 29 floats inside the hull of the ship, 17 miles offshore and 500 feet below the surface. Relatives of the deceased have requested that divers not intrude, so no bodies have been recovered from the wreckage. The families of the lost loved ones consider the ship at the bottom of the Lake Superior to be a tomb for their remains.

The Edmund Fitzgerald is arguably the most famous shipwreck of the Great Lakes. (Illustration by Geo Rutherford)

Of the 350 shipwrecks at the bottom of Lake Superior, there is one particularly famous steamship called the SS Kamloops. At 250 feet long and 2,226 tons, this steel freighter was a relatively small vessel for the Great Lakes in the 1920s. For three years, the ship’s responsibility was to carry cargo between Montreal, Quebec, and Thunder Bay, Ontario.

The Great Lakes often freeze in the winter, with ice sometimes covering the entire surface. The shipping industry would continue to move cargo until late into the winter months, with the occasional ship getting frozen in the ice or disappearing in a winter storm.

In early December 1927, the SS Kamloops was traveling between Lake Huron and Lake Superior. The crew was headed to the far west edge of the enormous lake, aiming for the docks at Thunder Bay.

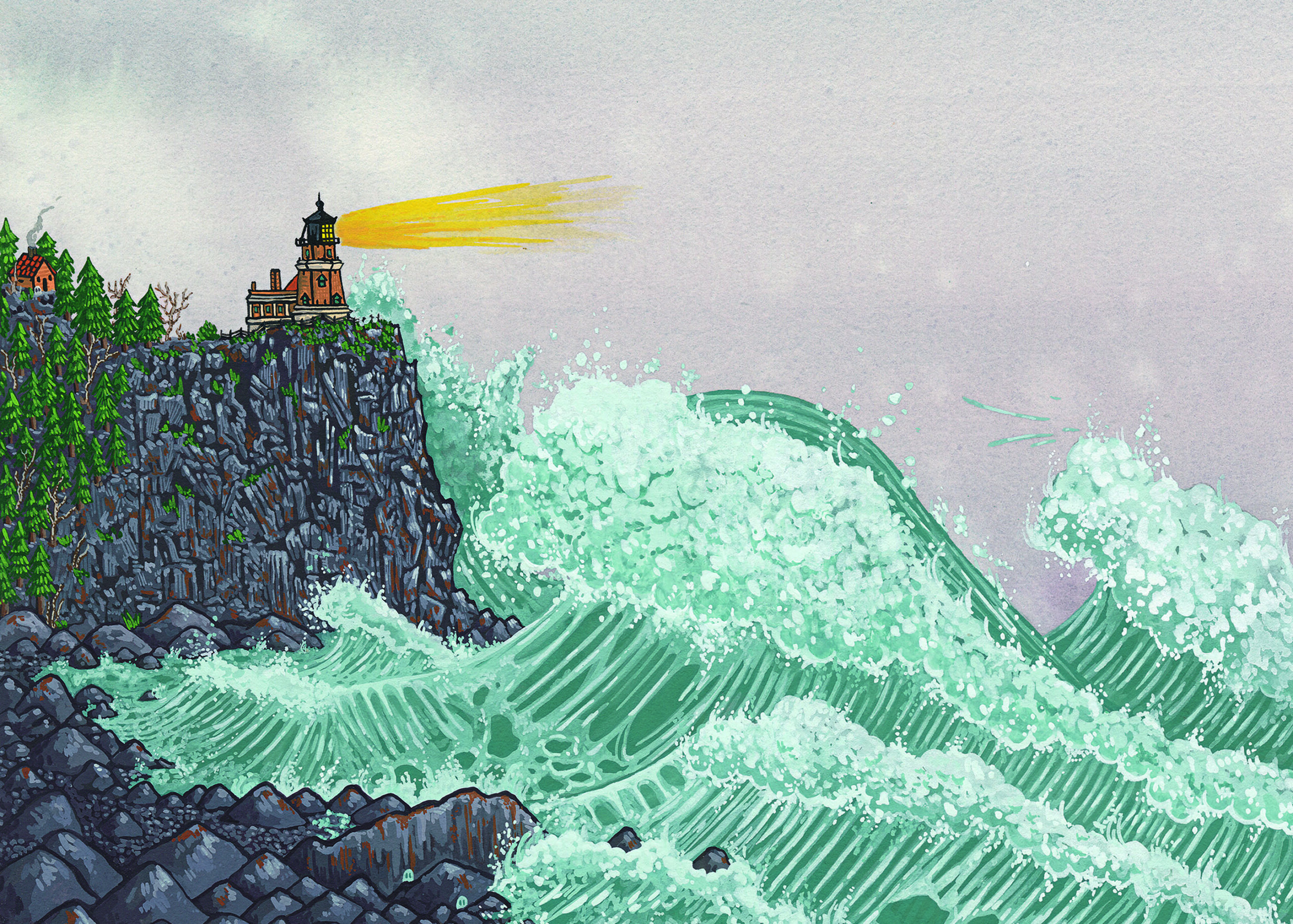

The weather was clear as they made their way through the locks at Sault Ste. Marie, but a northern wind was brewing, carrying an aggressive winter storm with it. The temperatures dropped below freezing, while the winds picked up to over 30 mph and the snow began to fall on the black waters of Lake Superior. The SS Kamloops was last seen steaming toward Isle Royale at dusk on December 6, heavily coated with ice. The 22 crew members aboard were never seen alive again.

The blizzard raged from December 7 to 8 with frigid below-zero temperatures, waves upward of 26 feet, and dense fog coating the surface of the lake. Multiple ships were reported missing, and the search for the SS Kamloops only began in earnest on December 12. The rescuers had little hope of finding survivors in the harsh winter conditions but scoured the shoreline nonetheless.

The blizzard raged from December 7 to 8 with waves upward of 26 feet. (Illustration by Geo Rutherford)

Months later, in May 1928, bodies were discovered on the northern shore of Isle Royale by a fisherman. The bodies, wearing life preservers stenciled with the word KAMLOOPS, were found alongside fragments of a lifeboat and oars. The remains were heavily decomposed, and only five of the nine recovered corpses could be identified and returned to their families.

A year after the SS Kamloops disappeared, a message in a bottle was found across Lake Superior, over 150 miles away from Isle Royale. The handwritten note was penned by Alice Bettridge, a young assistant stewardess on the ship. The mangled paper told of the wreck and how she made it to shore. She wrote, “I am the last one left alive, freezing and starving to death on Isle Royale. I just want mom and dad to know my fate.”

It wasn’t until 1977, fifty years after the SS Kamloops disappeared, that divers found the wreck beneath the black waters of Lake Superior. Bacteria that typically would have destroyed the hull cannot survive in the deep, cold fresh water, so the metal hull and cargo were in near-perfect condition, undisturbed at the bottom of the frigid lake. The wreck rests in pitch-black conditions, with only portions of the ship visible at a given time, illuminated by lamps of visiting divers: a flagpole emerging form the dark, a barrel, a ladder. The only sound is the divers’ own breathing and the bubbles percolating from their suits.

The SS Kamloops wreck still contains cargo from that last voyage: candy Life Savers, toothpaste, wooden barrels, and farming tractors. The divers that discovered the steamer were also greeted by the long-lost crew of Kamloops.

If someone dies in a very cold freshwater lake, their body doesn’t decay the way it would in other situations. (Illustration by Geo Rutherford)

They looked as fresh as the day they drowned. One crewmate in particular never left his post in the belly of the ship. His corpse, known as “Old Whitey,” floats around the boiler room, where currents from diver’s fins made it seem like the boy was following them round the waterlogged space. Considering this corpse was nearly 50-years-old, the lack of decomposition shocked the divers. His flesh seemed to glow from within — a bright spot in the rusted metal boiler room.

If someone dies in a very cold freshwater lake, their body doesn’t decay the way it would in other situations. Typically, bacteria helps to break down bodily remains and eventually leaves behind a skeleton. Lake Superior is so deep and cold that her is a lack of bacteria at the bottom of the lake. The cold fresh water can generate a chemical reaction between minerals in the water and human skin that results in a substance called adipocere. The chemical reaction sis called “saponification,” which is a process that turns body into a soap-like substance. The resulting adipocere is also known as corpse wax or the fat of graveyards. The wax has a soft, greasy appearance when it first starts to form, but as it ages, the wax hardens and turns brittle. Saponification stops the decay process in its tracks, so a soap mummy can remain intact for potentially hundreds of years, even after the bones have begun to disintegrate. Old Whitey, one of the most famous permanent residents of the Great Lakes, is preserved in this way, which accounts for his glowing aspect.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Behind the shipwreck discovered in Lake Michigan

I Speak for the Fish: Water snakes are spooktacular

Featured image: It wasn’t until 1977, fifty years after the SS Kamloops disappeared, that divers found the wreck beneath the black waters of Lake Superior. (Illustration by Geo Rutherford)