By Phil McKenna, Inside Climate News

This article originally appeared on Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, non-partisan news organization that covers climate, energy and the environment. Sign up for their newsletter here.

LUDINGTON, Mich.— Boarding the S.S. Badger, a 410-foot freight and passenger ferry that crosses Lake Michigan each summer, is like stepping back in time. A National Historic Landmark, the ship retains many of the original components from when the vessel first entered service in 1953: train tracks that once carried railcars, a telegraph system the captain still uses to communicate with the engine room and two massive engines powered entirely by coal.

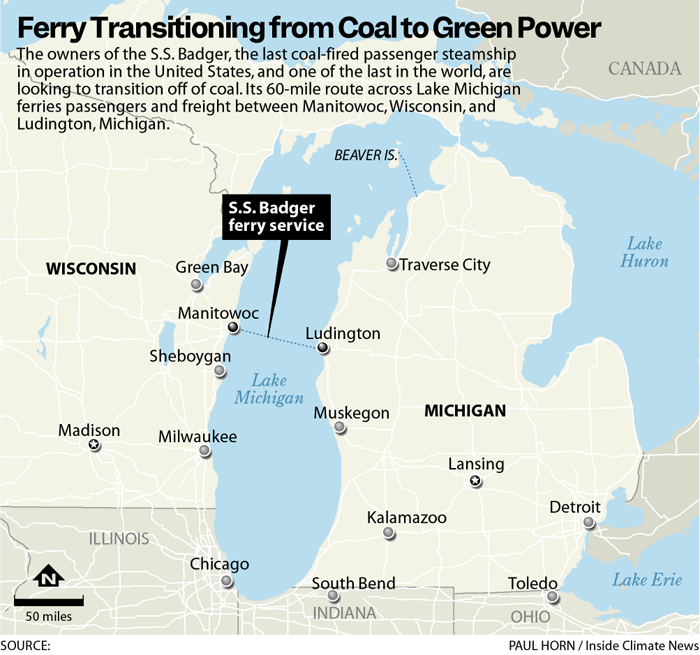

Thirteen tons of coal for each 60-mile crossing, to be precise.

It’s the last coal-fired passenger steamship in operation in the United States and one of the last in the world.

“It’s historic, it’s romantic,” said Mark Barker, the president of Interlake Maritime Services, which purchased the ship four years ago and is now looking to transition the Badger off coal. But “in today’s world, it’s not a long-term sustainable solution,” he said, noting the environmental as well as mechanical challenges of maintaining the old coal-burning technology on the Badger, which completed its final voyage of the year this week.

As recently as 2014, Lake Michigan Carferry, the ship’s prior owner, dumped nearly 1 million pounds of toxic coal ash from the S.S. Badger into Lake Michigan each year as the ferry made the crossings between Ludington, Michigan, and Manitowoc, Wisconsin, multiple times each day from May to October.

The Environmental Law and Policy Center, a nonprofit based in Chicago, led a campaign that resulted in a federal consent decree requiring the company to retain the coal ash aboard the Badger and dispose of it on shore.

The ship continues to burn coal, however, as evidenced by plumes of black smoke that billow from the ship as it makes its way across the lake. In a tongue-in-cheek nod to the fossil fuel, a crew member hands out a lump of coal to anyone who incorrectly calls out “bingo” during games of “Badger Bingo” played during the leisurely four-hour crossings.

Below deck the engines roar as additional crew members, including a “coal passer” and “fireman” feed the ship’s boilers, which send steam to a pair of massive, 3,500-horsepower engines that power the ship’s propellers. In the boiler room’s upper reaches, ambient temperatures can reach 185 degrees Fahrenheit.

“We try to avoid spending unnecessary time there,” said Andy VerVelde, a chief engineer on the S.S. Badger.

VerVelde, a 35 year old with a thick mustache and goatee, said he’s been interested in steam ships since he was four or five years old. A graduate of the Great Lakes Maritime Academy in Traverse City, Michigan, VerVelde has worked on nearly every steam-powered ship on the Great Lakes, a number that has shrunk from the teens to just five during his short career.

“Every year there’s less and less,” he said.

Andy VerVelde, a chief engineer on the S.S. Badger, shovels coal into a boiler that supplies steam to a pair of 3,500-horsepower engines. Coal is typically fed by conveyor belts but can still be manually shoveled into the boiler. Credit: Phil McKenna/Inside Climate News

VerVelde gives frequent tours to former engineers and crew members who used to work on the S.S., or “Steam Ship,” Badger or on similar merchant ships or Navy vessels. He speaks passionately about the equipment he oversees.

“The machinery has its [own] personality,” he says. “It’s more than just a boiler, or more than just an engine. Each of my boilers is unique. Each engine operates individually, and you develop a sort of relationship with it. I don’t know that you do that so much with modern technology, but it’s definitely something that you develop working with steam engines.”

Efforts to repower the Badger come at a pivotal moment for steam and coal. A high-profile effort to preserve the S.S. United States, a once-luxurious ocean liner that entered into service just one year before the Badger, seem unlikely to keep the ship afloat. Meanwhile, the United Kingdom, the birthplace of the coal-fueled Industrial Revolution, shut down its last coal-fired power plant earlier this month.

Though there are currently no state or federal regulations prohibiting coal-powered ships, VerVelde said he realizes the Badger can’t continue burning coal forever.

“It’s important to look at the future and look at options and try to figure out what the best path forward is,” VerVelde said. “But in the meantime, we enjoy what we do. We try to keep it alive and we enjoy sharing it with people.”

Charting a New Direction for an Old Ship

In September 2023, Lake Michigan Carferry, now a subsidiary of Interlake, received a $600,000 grant from the federal government for a feasibility study to look at how the Badger could transition to a zero-emissions vessel.

Katie Wells, environmental stewardship manager for Interlake, said there are a number of potential technologies on the table, including battery-powered electric motors and diesel-electric hybrid power paired with carbon capture for the CO2 released from burning diesel. Wells said keeping some or all of the coal-fired engines in a non-operating state is also a possibility, both for historic preservation and as part of the ship’s ballast.

Barker, the company’s president, said a hybrid diesel-electric system could allow the ship to rely fully on battery power while in port, using diesel fuel to provide some or all power when the ship is in open water.

“We’ve looked at how to use batteries in certain parts of the operation so that we can be completely electric for shorter periods of time,” Barker said.

He added that they will be taking a closer look at carbon capture to see if it’s a viable option to eliminate carbon dioxide emissions. The Badger could potentially serve as a test case for the company’s 13-ship fleet, Barker said.

“We’re trying to figure out how to decarbonize all of our ships over the long haul,” he said. “The Badger could be an interesting platform to test some of those technologies.”

State and regional ferry operators elsewhere in the U.S. are pursuing diesel-electric hybrid power as a way to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and other pollutants from their ships. Washington state, which operates the largest passenger ferry system in the country, recently embarked on a massive $4 billion electrification program that aims to convert its entire fleet—currently 21 ferries—to diesel-electric hybrid power by 2040.

The Delaware River and Bay Authority, a regional transportation agency, recently received a $20 million grant from the U.S. Department of Transportation to help build a new diesel-electric hybrid ferry to replace an existing diesel ferry connecting Cape May, New Jersey, and Lewes, Delaware.

Carbon dioxide and other pollution from burning coal still spew from the ship’s smokestack, though far less than it used to be. Credit: Phil McKenna/Inside Climate News

Corey Ottgen, a wheelman aboard the S.S. Badger, steers the vessel across Lake Michigan. Credit: Phil McKenna/Inside Climate News

On July 30, the state of Michigan included $2 million in its annual budget for Lake Michigan Carferry’s “decarbonization planning and implementation” for the S.S. Badger.

“This money will help move this initiative forward,” Barker said. “We are currently exploring ideas and will discuss this with the state of Michigan to find ways to put this money to good use.”

Michigan state Rep. Curt VanderWall, a Republican whose district includes Ludington and who wrote the line item for the Badger into the state’s budget, said he hopes the funds will help the company secure additional federal money for the project.

“This is just moving a great ship into the future,” VanderWall said.

Barker said his company is exploring other funding options but declined to provide additional information.

As the Badger approaches the Wisconsin side of the lake, a pair of smokestacks emerge from the shoreline, highlighting another challenge the company may face in its efforts to reduce emissions.

A power plant owned by Manitowoc Public Utilities, just south of where the Badger docks, has for decades burned coal and petroleum coke, a byproduct of oil refining. If a future hybrid diesel-electric Badger connects to the grid in Manitowoc to recharge its batteries, the electricity it takes onboard would have associated emissions. But that pollution will likely fall over time as the utility shifts to cleaner fuels.

The city-owned utility is now transitioning to burning waste from nearby paper mills, which it says will cut greenhouse gas emissions by more than half by reducing methane that would otherwise be released at landfills. It’s also building a community solar farm.

Howard Learner, executive director of the Environmental Law and Policy Center, the environmental organization that pushed the ship’s prior owners to stop dumping coal ash into Lake Michigan, said his organization is keeping a close eye on Interlake’s efforts.

“We’re hoping that their actions will live up to their words about sustainability, but if they don’t, we will otherwise move forward with public advocacy actions,” Learner said.

Correction: A previous version of this story had an incorrect name for the parent company of Lake Michigan Carferry. It is Interlake Maritime Services.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Midwest States Struggle to Fund Dam Safety Projects, Even as Federal Aid Hits Historic Highs

Featured image: Travelers relax on the top deck of the S.S. Badger as it crosses Lake Michigan from Ludington, Mich. to Manitowoc, Wis. Credit: Phil McKenna/Inside Climate News