By Kelly House

The Great Lakes News Collaborative includes Bridge Michigan; Circle of Blue; Great Lakes Now at Detroit Public Television; Michigan Public, Michigan’s NPR News Leader; and who work together to bring audiences news and information about the impact of climate change, pollution, and aging infrastructure on the Great Lakes and drinking water. This independent journalism is supported by the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation. Find all the work HERE.

- A new federal rule requires lead pipes to be removed from drinking water systems within 10 years

- Officials have long understood the perils of lead pipes, but momentum for policy change only began after the Flint water crisis

- Flint pediatrician calls the rule ‘a game changer for kids and communities’

Michigan communities and others nationwide have a decade to remove lead-containing pipes from their drinking water systems under a landmark federal rule finalized Tuesday.

The rule also lowers the allowable limit for lead in drinking water from 15 parts per billion (ppb) to 10 ppb and requires water testing in schools that get their drinking water from public utilities.

Those regulations are more aggressive than Michigan’s state lead and copper rule, which has a 15 ppb limit that was set to be lowered to 12 ppb next year, and requires lead pipe removal by 2041.

Yet some contend they’re still not aggressive enough to offer complete protection against a neurotoxin so potent, there is no safe level. Lead accumulates in teeth and bones, damaging the brain and nervous system. Particularly dangerous to children who are still developing, it has been linked to learning and behavioral problems, and other health issues including cancer.

Thirty-nine Michigan water systems exceeded the new federal threshold in their latest round of testing. Preliminary inventories submitted to the state by Michigan water supplies show just under 309,000 pipes that either certainly or likely contain lead.

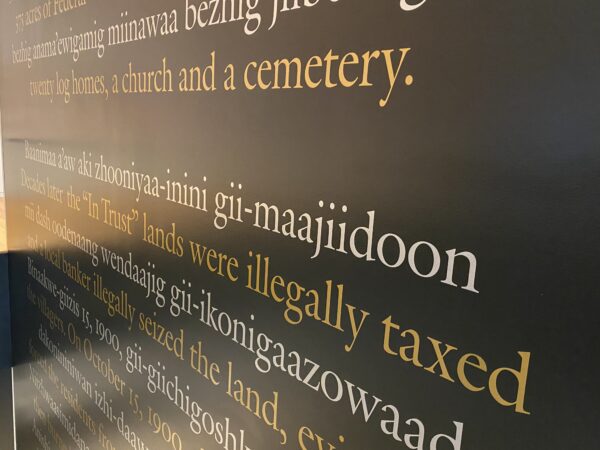

Regulators have known for decades of the perils posed by lead pipes, but the push to remove the neurotoxic metal from drinking water systems only gained steam after corroding lead pipes caused the Flint water crisis in 2014.

In a statement Tuesday, EPA Administrator Michael S. Regan hailed the new rule for “putting an end to this generational public health problem.”

“With the Lead and Copper Rule Improvements and historic investments in lead pipe replacement, the Biden-Harris Administration is fulfilling its commitment that no community, regardless of race, geography, or wealth, should have to worry about lead-contaminated water in their homes,” Regan said.

Role of Flint crisis

In Flint, a city financially ruined by decades of industrial disinvestment and population loss, state-appointed emergency managers looked to cut costs by approving a switch of the city’s drinking water source from Detroit’s water supply to the polluted Flint River. They didn’t require chemical treatments to prevent corrosion, so lead leached out of pipes and into the water.

While residents complained about the water’s color and smell, officials denied there was a problem for a year-and-a-half. Despite a lengthy criminal investigation, no public officials stood trial for their role in the crisis.

But Flint’s experience drew attention to the lead hazards lurking in water systems across the country, prompting calls for reform. EPA officials estimate 9 million homes are served by lead-containing pipes. Removing them all is expected to cost tens of billions of dollars.

The federal infrastructure law made $26 billion available, including $2.6 billion announced Tuesday. Nearly half of that money must be funneled into disadvantaged communities, which tend to have the highest concentrations of lead pipes and the fewest resources to remove them.

But even with the influx of federal money, local governments will be hard-pressed to meet the escalated deadline, said James McNeil, city manager for Escanaba.

Escanaba has been excavating its lead pipes at a rate of about 200 a year, and has about 3,800 left to go. It has received some $60 million in federal funding for a range of water system upgrades including lead pipe removal, but McNeil said the cost-per-service line has tripled from about $5,000 to $15,000 amid inflation and stiff competition for contractors.

“We are getting more work done here than we’ve probably ever seen,” McNeil said. “But at the same time, if we were given more time to use that funding, I think we would have seen our dollars go a lot further. We wouldn’t have all been trying to use the same contractors and buy the same materials at the same time.”

In a statement Tuesday, the Flint pediatrician credited for exposing Flint’s water crisis called the new rule “a game changer for kids and communities.”

“EPA’s finalized lead and copper rule improvements will ensure that we will never again see the preventable tragedy of a city, or a child, poisoned by their lead pipes,” said Dr. Mona Hanna. “I commend the Biden-Harris administration for their steadfast efforts to finally update this ancient rule, and I am thrilled that this rule proactively centers our children and their potential. The children win!”

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Palisades nuclear relaunch gets more subsidies in Michigan — and more backlash

Michigan’s electric energy future could be wasting away in a junk drawer

Featured image: Communities across the nation would have to remove lead-containing pipes and service lines, like the one shown here, within 10 years under a new federal rule. (Bridge file photo)