“Nibi Chronicles,” a monthly Great Lakes Now feature, is written by Staci Lola Drouillard. A Grand Portage Ojibwe direct descendant, she lives in Grand Marais on Minnesota’s North Shore of Lake Superior. Her nonfiction books “Walking the Old Road: A People’s History of Chippewa City and the Grand Marais Anishinaabe” and “Seven Aunts” were published 2019 and 2022, and the children’s story “A Family Tree” in 2024. “Nibi” is a word for water in Ojibwemowin, and these features explore the intersection of Indigenous history and culture in the modern-day Great Lakes region.

The rice harvest — manoominike — has officially started across Ojibwe country. To say it is a long-standing “tradition” falls short, because Ojibwe people have been harvesting, parching, dancing on, and winnowing this native grain for 1,000s of years. Manoomin — the good berry — or, wild rice, is a survival food as well as a ceremonial one.

When I was a kid, I thought that everyone ate manoomin, especially during the fall grouse hunting season, to be eaten with an equal portion of slow-braised partridge, or as my dad says, “pinay,” cooked in an oven cream sauce. That’s how Grandma Lola used to make it, and I’ve never quite been able to make it taste as good as she did. Other people are purists about their rice, which is understandable.

“I like it plain, with just a little salt and butter,” my Drouillard-Anakwad cousin, Sue Zimmerman, once declared over cups of tea at her kitchen table in Grand Portage.

Sue Zimmerman learned about harvesting manoomin from Maeda and Vincent Bender from the Bad River Band Ojibwe Reservation, on the south shore of Lake Superior. Back in the 1980s the elderly couple were visiting Grand Portage for the annual Rendezvous Days Pow Wow. One of Sue’s cousins introduced them and they became good friends. She was invited to visit them at Bad River during rice processing time.

“They processed lots of rice,” said Sue. “I helped by running two of their machines. They also made moccasins. Vincent did the deer hide processing in the attic of their house. They both made the moccasins and Maeda did the beadwork. I am very honored to own a pair and danced in them a few times.”

The Benders lovingly passed along their manoomin harvesting techniques to Sue, who has continued to harvest and process rice ever since.

“They were such sweet caring folks,” she said. “They purchased a heavy-duty winnowing basket from Jim Northrup (Fond du Lac) and gave it to me. With a few minor repairs I still use it today many years later.”

Under Siege

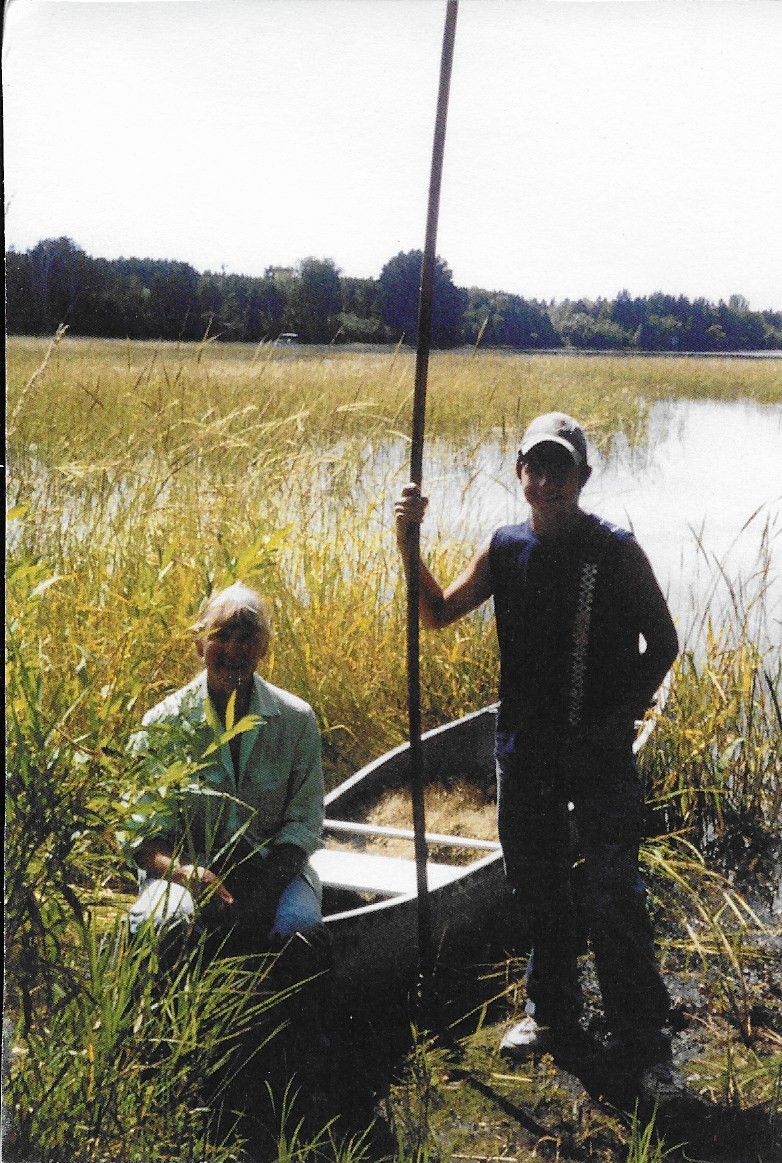

Sue and her grandson Tanner. (Photo courtesy of Sue Zimmerman)

There are some rice lakes and rivers relatively close to Grand Portage, but the closest paddies are either small, or very far inland. For the most part, wild rice waters are under siege across Anishinaabe Aki. According to the Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission: “development following European immigration to the Great Lakes region has taken its toll on wild rice stands. Some historic rice fields no longer exist, and others are far less abundant. The valued plant has suffered from environmental changes such as water level fluctuations from dams, the use of motorized boats tearing up the fragile stalks and the introduction of exotic plants.” This makes every grain of manoomin a precious gift.

I asked Sue if she knew any family ricing stories and she said, “I have not heard of any family ricers. The only story concerning wild rice is my dad saying they used to buy it for 5 cents a lb. when he was growing up.”

For historical context, hand-harvested manoomin now sells for $15 – $25 a lb., depending on whether you purchase it from a retail outlet, or directly from a tribal purveyor.

Sue started ricing in the early 1980s and began processing rice on her own in 1997, not only her rice but also for other ricers. The launch of her processing venture corresponded with a divorce, which did not slow down Sue’s work on the harvest.

“The first season [my husband] left I had nine other people pole me through the rice beds,” Sue said. “One of my college friends from New York state was one of them. She still says it was one of the highlights of her life. One night we kept processing while it was raining and thundering while we worked under the tarp.”

Sue will soon be 85, and is still actively processing rice — which amounts to many years observing the harvest and conditions in the rice beds. I asked her for her anecdotal take on how these places are doing today, compared to 44 years ago.

She shared that: “some places I used to rice are now taken over by water plants of all kinds. One lake in particular, in the area where I live now, there is hardly any rice, and each year there is less and less. Other friends have also riced there, and it was fun, as ricing season was the only time I saw them. I have heard other ricers say they also know places like that in other ricing areas.”

The threat to manoomin is real. Great Lakes Ojibwe bands from Bad River to Fond du Lac have been engaged in an environmental fight to uphold the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) water quality standards put in place in the 1970’s, which set the standard at 10 mg/L sulfate.

As Sue says, “If the mining on the edge of the BWCAW [Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness] and other areas go through they will undoubtedly wipe out many ricing areas.”

Sue then brought up another impending threat to wild rice waters in the form of climate change, when warmer winters directly affect the health of manoomin. She said that this was a bad year for harvesting because of storms and high water, and that she talked to many disappointed folks.

“Students working with the 1854 Treaty Authority and Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wild Life Commission monitoring data, show that wild rice tends to do better after harsher (more snow and cold) winters,” said Sue. “Concern exists about the trend to warmer temperatures.”

Indeed, manoomin is listed as a “highly vulnerable” plant in the Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC) Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment which states: “Ice cover on waterbodies in the winter provides low oxygen conditions that help the seed emerge from dormancy in the spring. Thickness and duration of ice cover also has an influence on aquatic plant competition – thicker and longer-lasting ice will prevent perennial and/or non-local beings from outcompeting this annual plant.”

Every Grain is Precious

Sue and a friend. (Photo courtesy of Sue Zimmerman)

The current rice forecast for the entire 1854 Treaty Area is mapped out and coded in red, yellow and green dots, indicating poor, fair or good conditions for rice. Each tiny dot represents a body of water that at one time supported manoomin plants.

In Sue’s opinion, “the 1854 Authority is keeping a very important eye on rice beds and are to be commended — and also because they are teaching young people the importance of ricing and the tools needed in order to rice and process it.”

“Process,” a very small word, especially when it comes to the manoomin harvest. Anyone who has knocked ripe rice into the canoe, gathered it up in a tarp, planted some ceremonial seed rice back into the lake, tenderly dried it in the sun and then dried it further over a woodfire, danced on it in soft moccasins and then waited for the perfect (but not too much) wind to winnow it, knows that the process is more like a ceremony than an agricultural harvest.

“There is no way to adequately impart to folks exactly what kind of work it takes to process rice unless they observe it,” said Sue. “I think even ricers themselves don’t understand the tedious process unless they have tried it themselves — especially for those few of us who parch with wood.”

Indeed, until you have experienced how difficult the process is, one can never understand why every single grain that makes it onto your plate is a precious gift that connects people to the land.

I asked Sue about her own connection to the land, and she said:

“Having spent many years growing up in the woods 32 miles to the nearest town, Grand Marais, I feel a strong connection to the woods — the two-leggeds, the four-leggeds, the water and the sky. It is a part of me and who I am as a person.”

I asked her if she preferred rice from a certain place and she offered that “the water content, the soil in the lake bottom, the flowage of water — are all a part of wild rice growing well,” said Sue. “It also affects the size and taste of the rice. Some people think longer grains look better but it is not the length of the grain that affects the taste. I know some folks who only like rice from a certain place. I’m not that picky and enjoy rice from many places.”

She sees a dedicated continuation at the Grand Portage, Bois Forte, and Fond du Lac communities, who are all teaching the traditions and culture pertaining to wild rice. According to Sue, it has been a long time coming and we can only hope that the tradition and the wild rice crops will continue to thrive and grow.

When I talked with Sue at her rice and fine art stand at the Grand Portage Pow Wow in August, she still had some of her and her husband’s hand-parched rice left, perfectly processed and packaged with a pretty label.

They work with many different harvesters, offering to process rice in exchange for a percentage of the harvest. They’ve had a lot of the same ricers over the years, who have become friends.

That’s when she told me: “I like processing rice. It is long, tedious, dirty work but there are so few people who process small batches, so we are really doing them a service. I like that aspect and it’s also why we keep processing even though we have quit ricing.”

Even though Sue doesn’t get out in a canoe very often, continuing to process rice for others provides for plenty of work keeping the machines running, and the oak wood split into small enough pieces so it will burn with a slow, steady heat.

“It is also a way we can get rice processed the way we like it and make our customers happy,” said Sue.

I look forward to having Sue’s rice with roasted squash, drizzled with maple syrup from last spring’s harvest here on Good Harbor Hill. An act of culinary defiance, a feast by any measure.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Nibi Chronicles: A conversation about Ojibwe history in Fur Trade Nation

Ojibwemodaa! Let’s speak Ojibwe!

Featured image: Eight or ten years ago, a big storm went through and took out the dam. Most of the water drained out, leaving the river bottom and no rice. The Park Service put in graduated rocks to form a small watershed; the water returned but little rice. (Photo courtesy of Sue Zimmerman)