Great Lakes Moment is a monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor John Hartig. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit PBS.

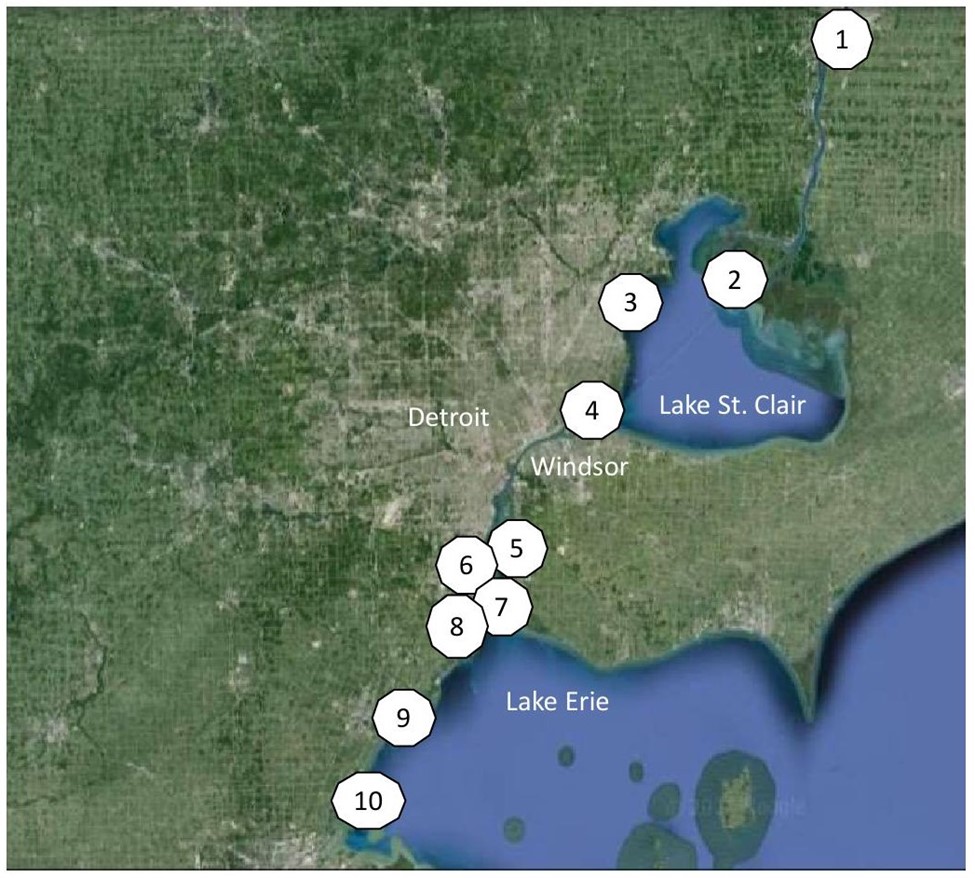

The Great Lakes Way is an interconnected set of greenways and water trails stretching from Port Huron, Michigan (at the head of the St. Clair River) to Toledo, Ohio on western Lake Erie. Its purpose is to help reconnect people with continentally significant natural resources, promote outdoor recreation with its many benefits, and foster a stewardship ethic.

The Great Lakes Way is an initiative of the Community Foundation of Southeast Michigan. A few years ago, the Southeast Michigan Council of Governments developed an interactive map to explore these greenways, blueways, and points of interest along the way. It gets updated periodically to stay current — so, get your bicycle or kayak ready and consider adding these to your Great Lakes adventure bucket list.

Presented below, from north to south, are ten close-to-home natural wonders that are sure to inspire a sense of wonder.

1. Head of the St. Clair River — Where Sturgeon is King

All the waters of Lakes Superior, Michigan, and Huron roar through the St. Clair River on their journey to the lower Great Lakes — Lakes Erie and Ontario — and eventually to the Atlantic Ocean through the St. Lawrence River. The St. Clair River is a lake sturgeon hotspot, supporting the largest remaining free-ranging population in the Great Lakes.

Lake sturgeon is a remnant of the dinosaur age and is considered a species of special concern by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and “a globally rare species” by The Nature Conservancy. Fast-flowing currents, scoured rock habitats and high dissolved oxygen concentrations in the St. Clair River that make these waters ideal for spawning.

Fishery surveys performed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in the upper St. Clair River have estimated the population at more than 20,000 sturgeon. This ecological phenomenon even supports an annual Sturgeon Festival attracting thousands. Festival participants can view and touch a live sturgeon in a tank, get involved in hands-on activities, workshops, and Native American ceremonies while enjoying food, music or the majesty of the river.

2. Clair Delta — The Largest Delta in the Great Lakes

As the St. Clair River flows south and enters the northern part of Lake St. Clair, it braids into several channels forming the St. Clair Delta (also called St. Clair Flats). This nearly 20,000-acre delta is the largest in the Great Lakes and one of the largest freshwater deltas in the world. It is often called a bird’s foot delta because its formation looks like a bird’s claw.

This delta, and its significant wetlands, provide nursery habitat for a variety of fish species that help support nationally acclaimed muskie and smallmouth bass fisheries in Lake St. Clair. It has also been designated an “Important Bird Area” (IBA) by BirdLife International. The delta is one of 13,000 designated IBAs from around the globe, considered very important for the conservation of bird populations like waterfowl — as well as vulnerable wetland species like the American bittern, black tern and marsh wren.

Whether it is fishing or birdwatching, this geological formation and nursery of life is a must-visit for those seeking outdoor adventure and natural beauty.

3. Edsel and Eleanor Ford House — One Mile of Living Shoreline on Lake St. Clair

The Edsel and Eleanor Ford House is a National Historic Landmark located on Lake St. Clair in Grosse Pointe Shores. Edsel was the only son of Henry and Clara Ford. His 87-acre historic lakeside estate opened to the public in 1978. Now, the Ford House is doing its part to change the fact that less than 0.1% of Lake St. Clair’s shoreline remains in a natural condition.

In 2023, they received $7 million from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) for restoring natural habitats in the estate’s Ford Cove on Lake St. Clair. Specifically, this project will remove hard features like broken concrete and seawalls, and restore a living shoreline made up of native plants, sand, or rock to reduce erosion by providing valuable habitats that promote coastal resilience. This will help the ecosystem’s capacity to respond to disturbances like climate change, and associated flooding, by resisting damage and more easily recovering.

It is one of only a few opportunities for large-scale shoreline restoration on the U.S. side of Lake St. Clair. In total, it will restore a living shoreline with approximately five acres of coastal marsh, eight acres of nearshore habitat and four acres of forested wetland — one mile of Lake St. Clair.

4. Belle Isle — The Crown Jewell of Detroit Parks

Rich with history and natural beauty, Belle Isle is a 982 acre island park in the Detroit River designed by Frederick Law Olmsted. Olmsted is considered the “father of landscape architecture,” and is most well-known for creating New York City’s Central and Prospect parks.

Key features of Belle Isle include the Anna Scripps Whitcomb Conservatory, Belle Isle Aquarium, Dossin Great Lakes Museum, Oudolf Garden, James Scott Memorial Fountain, three lakes, 200 acres of forest, athletic fields, public beach, picnic areas, spectacular views of the Detroit and Windsor skylines, and more. Belle Isle is managed by the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, with considerable support from the Belle Isle Conservancy and many other partners.

Since 2014, $140 million has been spent on capital improvements, including $6 million for habitat restoration, to reestablish the luster of this island oasis. Belle Isle currently has more than five million annual visitors, making it the second-most-visited state park in the United States behind only Niagara Falls, New York.

5. Conservation Crescent — A Half-Moon-Shaped Collection of Islands and Shoreline Habitats

The conservation crescent is a lunar-shaped grouping of islands and coastal habitats that span the lower Detroit River as it enters western Lake Erie. Local conservationists coined this term in a fight to protect several islands and marshes from residential development 25 years ago. The conservation crescent includes eight islands: Stony, Boblo, Sugar, Grosse Ile, Celeron, Calf, Humbug, and Wayne County’s Elizabeth Park (formerly Slocum’s Island), and coastal areas like Gibraltar Bay and Humbug Marsh.

Restoration and conservation of these unique habitats is particularly noteworthy because of metropolitan Detroit’s longstanding reputation as the industrial heartland and rust belt. Collectively, the diversity and quality of these habitats are a major reason why the lower Detroit River is also identified as an IBA by BirdLife International.

In addition, these coastal habitats are critically important to supporting a world-class fishery. Indeed, Detroit River wetlands provide spawning areas for 26% of the fish species in the Great Lakes. Further, an estimated 10 million walleye ascend the Detroit River from Lake Erie each spring, creating an internationally renowned sport fishery.

6. Humbug Marsh — Michigan’s Only Wetland of International Importance

In 1998, Detroit River’s Humbug Marsh, the last mile of natural shoreline on the U.S. mainland of the Detroit River, was threatened by residential development. Citizens strongly opposed this development and wanted to save this natural coastal area that was part of their home and heritage. Citizens eventually won and this valuable natural resource was preserved as the cornerstone of the Detroit River International Wildlife Refuge.

There are currently over 2,400 Ramsar Wetlands of International Importance throughout the world, 41 in the United States and only one in Michigan being Humbug Marsh. An adjacent industrial brownfield was also successfully cleaned up to serve as an ecological buffer to the marsh and for a gold, Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design visitor center. This transformed brownfield is now called the Refuge Gateway.

Other amenities include a 740-foot fishing pier and school ship dock, a canoe and kayak launch, three wildlife observation decks, an outdoor environmental education classroom, and over three miles of hiking trails connected to over 100 miles of regional greenway trails.

The preservation of Humbug Marsh and the cleanup of the adjacent industrial brownfield for the refuge’s visitor center is now widely recognized as being transformational for metropolitan Detroit. It is helping change the perception of the Detroit River from that of a polluted “rust belt” river to one of an international wildlife refuge that reconnects people to nature, promotes outdoor recreation, improves quality of life, and enhances community pride.

7. Lake Erie Metropark — One of North America’s Best Places to Watch Hawk Migrations

The Detroit River is at the intersection of the Atlantic and Mississippi Flyways making it a unique area to survey migrating birds, especially raptors. For more than 30 years citizen scientists have been tracking raptor migrations at Lake Erie Metropark.

This metropark is located just off the mouth of the Detroit River in Brownstown Township. It is 1,607 acres, with three miles of captivating shoreline. What makes this site so unique is its geography and the migratory preferences of raptors. As raptors move south from their eastern Canadian breeding grounds, they are blocked by the north shore of Lake Erie. Thermals are rising columns of warm air caused by the heating of the earth by the sun, and they do not form over water. Raptors use these thermals coming from the islands to fly over the lower Detroit River — a sort of hopscotching of archipelago islands.

Hundreds of thousands of raptors can be seen crossing the river each fall, including 23 different species. The Detroit River International Wildlife Refuge has been championing citizen science raptor monitoring, called Detroit River Hawk Watch, as an important tool in bringing conservation to cities.

Complementing this hawk watch is an annual birding festival called Hawkfest that is held each September to celebrate the migration of these birds of prey. This year, the free event will be held on Saturday, September 21.

8. Pointe Mouillee — Where Waterfowl Are King

Pointe Mouillee (pronounced “Point Moo-yay”) sticks out like a “big banana” along the Michigan shoreline of western Lake Erie. It got its name (i.e., meaning “wet point”) from the French in 1700s. In 1875, it became a shooting club and went on to have a national reputation as one of the most prestigious waterfowl hunting clubs in North America. In 1945, the State of Michigan bought 2,608 acres from the shooting club and established the Pointe Mouillee State Game Area.

Over time, this State Game Area would expand to include 4,040 acres of marsh, shallow open water, diked cropland, lake plain prairie, and lowland hardwood habitats. Then in 1952, several very large storms inundated and destroyed the marshland. This became the impetus for constructing 3.5 miles of barrier dikes that would both serve as a confined disposal area for contaminated sediments dredged from the Detroit and Rouge Rivers and that would halt the degradation of the marsh by rising water levels.

These diked disposal cells were constructed from 1976 to 1981 for $45.5 million (more than $250 million in today’s dollars). At the time, this was one of the world’s largest marsh restoration efforts. Today, Pointe Mouillee provides close-to-home, world-class hunting and wildlife observation opportunities to nearly seven million people in a 45-minute drive.

Ducks Unlimited identified metropolitan Detroit as one of the top ten urban waterfowl hunting areas in the United States, in part thanks to Pointe Mouillee. For 75 years, local hunters have held the Pointe Mouillee Waterfowl Festival – one of the oldest events of its kind in Michigan –to pass on a hunting tradition and a conservation ethic. Catch the festival this year on September 14 and 15.

9. Sterling State Park — A Great Lakes Camping Adventure

Sterling State Park is the only Michigan state park on Lake Erie. This 1,300-acre park has one mile of sandy shoreline and protects more than 500 acres of Great Lakes marsh and restored lakeplain prairie habitats. It is a top-rated and hidden gem for Great Lakes camping — voted one of the best campgrounds in Michigan.

It also features full-amenity cottages, a boating access site, trails, stargazing, premier walleye and perch fishing, and exceptional birding for waterfowl, shorebirds, songbirds, egrets, ospreys, and bald eagles.

In 2012, Sterling State Park completed restoring 18 acres of marsh and 32 acres of lakeplain prairie, installing water control structures to manage marsh water levels, and controlling invasive species like Phragmites with $3.2 million of funding from the federal Great Lakes Restoration Initiative. This state park has been described as a wild oasis with exceptional close-to-home outdoor recreation in the middle of a heavily urbanized area.

10. Erie Marsh Preserve — Wetland Restoration in Action

Erie Marsh Preserve is a 2,217-acre coastal wetland that represents 11% of the remaining marshland in southeastern Michigan. It is also one of the largest marshes on Lake Erie. The Nature Conservancy acquired Erie Marsh from Erie Shooting and Fishing Club in 1978. At the time, it was considered highly altered, degraded wetland habitat that had been divided by barrier dikes and separated from Lake Erie since the 1950s.

In 2011, The Nature Conservancy, Erie Shooting and Fishing Club, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service initiated a four-phase restoration of 946 acres of high-priority coastal wetlands. This $7.5 million project was completed in 2023 and included refurbishing extensive wetland habitat, rehabilitating degraded levees, and installing a fish passage structure that reconnected the marsh to Lake Erie’s North Maumee Bay.

Erie Marsh is considered a globally important stopover site for migrating waterfowl, land birds, and shorebirds, and is home to the state-threatened eastern fox snake. It is also a breeding area for bald eagles and provides habitat for other rare plant and animal species.

The preserve’s nine miles of trails are open to the public from January through August but closed from September through December for waterfowl hunting season.

John Hartig is a board member at the Detroit Riverfront Conservancy. He serves as a Visiting Scholar at the University of Windsor’s Great Lakes Institute for Environmental Research and has written numerous books and publications on the environment and the Great Lakes. Hartig also helped create the Detroit River International Wildlife Refuge, where he worked for 14 years as the refuge manager.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Operation Manoomin: Restoring Wild Rice along the Detroit River

Great Lakes Moment: An ecosystem approach

Featured image: Ten natural wonders of The Great Lakes Way. (Photo Credit: Google Earth).