Experts now say “climate havens” are not places immune from climate change, but areas where adequate preparation is implemented to account for a drastically different climate than anticipated.

Great Lakes cities, like Chicago, are generally considered to be at a lower risk for extreme climate impacts such as wildfires and tropical storms. As this summer has demonstrated, Chicago is dealing with other problems — increasing extreme heat and precipitation trends.

Last year, Architectural Digest evaluated the climate resiliency of cities across the U.S. for 2024 by examining seven factors: population, elevation and projected sea level rise, extreme weather, health risk, readiness, air quality index, and clean energy ranking.

This reveals that a mixture of environmental and structural factors contribute to how a city will weather the effects of climate change. Chicago ranked 23rd, roughly in the middle of the 50 cities studied, for their climate positionality and preparation efforts.

According to the 2008 Climate Change and Chicago report, the number of days over 90 degrees Fahrenheit is likely to increase from 15 days every year to 35-56 days by the end of the century. The number of days over 100 degrees Fahrenheit is projected to increase to 30 days per year by the end of the century.

The report also predicted an increase in the frequency, duration, intensity, and season of heat waves in Chicago.

These predictions are underscored by the risk assessment of the 2024 Priority Climate Action Plan created by the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning (CMAP), which shows that Chicago is at a level nine risk for extreme heat and flooding.

On Monday, June 17, Chicago was hit with record-breaking temperatures reaching into the 90s. Coupled with the urban heat island effect, this increased the risk of public health impacts.

These warming trends also disproportionately affect underserved communities as cooling costs during the summer have increased nearly 10 percent from last year, compared to the 8 percent national average.

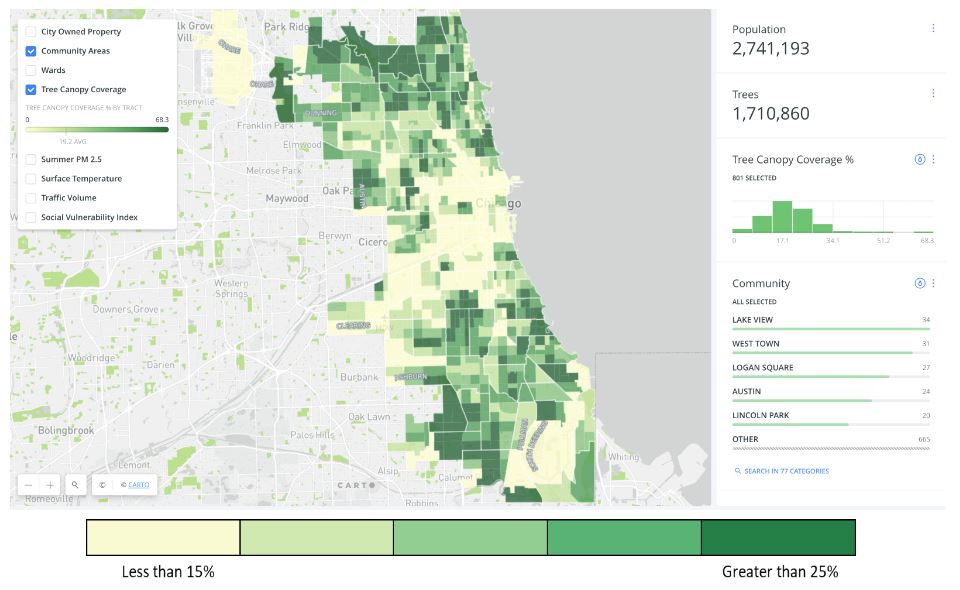

As the city heats up, the Chicago Department of Public Health (CDPH) is turning to green and gray infrastructure projects to mitigate the resulting health impacts. Director of Environmental Innovation at CDPH Raed Mansour is working to increase tree canopy land cover through the project, Our Roots.

Tree canopy coverage percentage by census tract. CDPH aims to better understand tree canopies in vulnerable communities to direct their efforts. (Photo courtesy of CDPH)

Our Roots is a community-driven, data-informed project that operates in 37 out of Chicago’s 77 total communities. There are over 50 groups partnered on this project, including city government alongside health, nonprofit, and social-environmental equity organizations.

“It’s really been great to see how the community organizations are able to shape the character of their neighborhood so that we can address gentrification, the historic redlining and the marginalization, disinvestment and under investment in these communities, and really co-develop and work with community,” said Mansour.

Chicago experienced a net loss of 69,000 street trees from 2011 to 2021. Our Roots began in 2022 with a goal to plant 75,000 trees within five years. Mansour says the organization is now over halfway to this goal.

“We can’t plant our way out of this, because it takes a while for these trees to grow,” said Mansour. “It shouldn’t be the only solution.”

Northwestern University’s Defusing Disasters Global Working Group is working with CDPH to develop a heat vulnerability index from the 2023 Heat Watch. Other solutions the city has implemented are public air-conditioned buses and six designated cooling centers through the Department of Family and Support Services.

With warming temperatures, the atmosphere is able to hold more water vapor, resulting in greater precipitation. For every one degree Fahrenheit the atmosphere warms, there is as much as a four percent increase in atmospheric water vapor.

On July 2 of 2023, Chicago experienced a record nine inches of rain in 24 hours. More than 12,000 flooded basement reports were filed with 311, the non-emergency city service line. There were more reports filed that month than in 2021 and 2022 combined.

“The city’s aging sewage system once again overflowed, unable to prevent massive flooding,” wrote Alderwoman Emma Mitts of the 37th Ward. With more flooding events from this summer consuming most of her time, she opted to give her comments via email. “TODAY — ONE YEAR LATER, many West side residents are still struggling with dangerous mold remediation, clean up measures, substantial property damage, lingering insurance claim issues and more financial difficulties.”

This July, Chicago experienced flash flooding as Tropical Depression Beryl brought two to four inches of heavy rain. The combination of increased temperatures and moisture also contributed to a derecho event that caused a record-breaking 32 tornadoes in a single day on July 15.

The annual total precipitation in Illinois has increased by around six inches from 1895 and 2019, or about a 15 percent increase, compared to the national average precipitation increase of four percent.

The Metropolitan Water Reclamation District (MWRD) of Greater Chicago is a government agency working to treat wastewater and manage stormwater. Their Strategic Plan for 2021-2025 has advanced over 200 stormwater management projects, including gray and green infrastructure, that are updated on a public data dashboard.

“We really do try to work with communities that have combined sewers,” said MWRD managing civil engineer Joe Kratzer. The MWRD also prioritizes underserved south suburban communities when addressing flooding.

One green infrastructure initiative of the MWRD is Space to Grow, which transforms asphalt lots into green schoolyards that store water in the soil beneath the surface. This partnership with Chicago Public Schools (CPS), the Chicago Department of Water Management (CDWM), Healthy Schools Campaign (HSC) and Openlands seeks multiple solutions to the increasing amount of precipitation.

The before and after of the green schoolyard project at Grissom Elementary School, which stores 253,902 gallons of stormwater. (Photo courtesy of MWRD)

These green schoolyards provide outdoor recreation and student learning opportunities while improving water quality and combatting flooding. The 34 completed schoolyards can hold over 192,000 gallons of water every time it rains, or enough to fill around ten Olympic swimming pools. The MWRD has secured their third agreement with CPS, allowing them to spend another $15.9 million on Space to Grow through 2026.

On the gray infrastructure front, the MWRD is working to finalize the second stage of the Tunnel and Reservoir Plan (TARP), which began construction in 1975. The completion of the McCook Reservoir in stage two will create an additional 6.5 billion gallons of storage for rainwater, helping the TARP system realize its full capacity at 17.5 billion gallons.

In July 2023, the TARP system’s overflowing tunnels forced district officials to release 1.1 billion gallons of combined sewer water into Lake Michigan, which isn’t the first time.

“With climate change challenges bringing more frequent and intense storm events in recent years, the Chicagoland area… served by the combined sewers are really more reliant on TARP than ever before,” said Kratzer. “This is one of the reasons we’re working diligently to complete stage two of the McCook Reservoir.”

Stage 1 of the McCook Reservoir between the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal on the left and the Des Plaines River on the right. Stage 2 is under construction in the back. (Photo courtesy of MWRD)

Kratzer says they recognize it’s not the one size fits all solution to flooding. The MWRD continues to seek supplemental solutions with local green and gray stormwater projects and reducing their carbon footprint.

The MWRD has new goals for the future, such as quicker project turnaround times, making their partnership process more efficient, and focusing on smarter long-term solutions.

“We know we can’t predict the size and intensity of future storms,” said Kratzer, “But we can try to plan for them.”

The 2024 Priority Climate Action Plan released by CMAP in March also aims for equitable investments in emission reductions, creating quality jobs, bolstering economic growth, and improving quality of life.

As climate change ramps up in Chicago, only the test of time will reveal the city’s capability to achieve climate resiliency.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

A New Paradigm: How climate change is shaping mental landscapes in the Great Lakes

Inside is Not the Answer: Air quality in the Great Lakes

Featured image: Heat and strong storms, including heavy precipitation, sweep Chicago from July 21-24, 2016. (Photo courtesy of Barry Butler for the National Weather Service)