“Nibi Chronicles,” a monthly Great Lakes Now feature, is written by Staci Lola Drouillard. A Grand Portage Ojibwe direct descendant, she lives in Grand Marais on Minnesota’s North Shore of Lake Superior. Her nonfiction books “Walking the Old Road: A People’s History of Chippewa City and the Grand Marais Anishinaabe” and “Seven Aunts” were published 2019 and 2022, and the children’s story “A Family Tree” in 2024. “Nibi” is a word for water in Ojibwemowin, and these features explore the intersection of Indigenous history and culture in the modern-day Great Lakes region.

Carl Gawboy is a citizen of the Bois Forte Ojibwe Nation in northern Minnesota. Of Ojibwe and Finnish descent, Mr. Gawboy has been teaching others about the history and everyday life of Ojibwe people for decades. I’m a fan of his art and an admirer of his books, such as Talking Rocks, co-written by Carl and geologist Ron Morton. Which is why I was excited to connect with Professor Gawboy about his new illustrated history book titled Fur Trade Nation: An Ojibwe’s Graphic History.

I asked how things were going so far, and he said, “I’m getting a lot of real great feedback from it. There’s one Ojibwe friend of mine that called it ‘a field guide to the Ojibwe.’”

An apt description, considering that the book includes nearly 1,000 drawings and encapsulates the arc of fur trade history, from 1650 to 1850. But the book does even more than that. Gawboy’s cartoons, compilated historical facts and personal stories bring the truth about Ojibwe people’s involvement in the Fur Trade economy to the forefront.

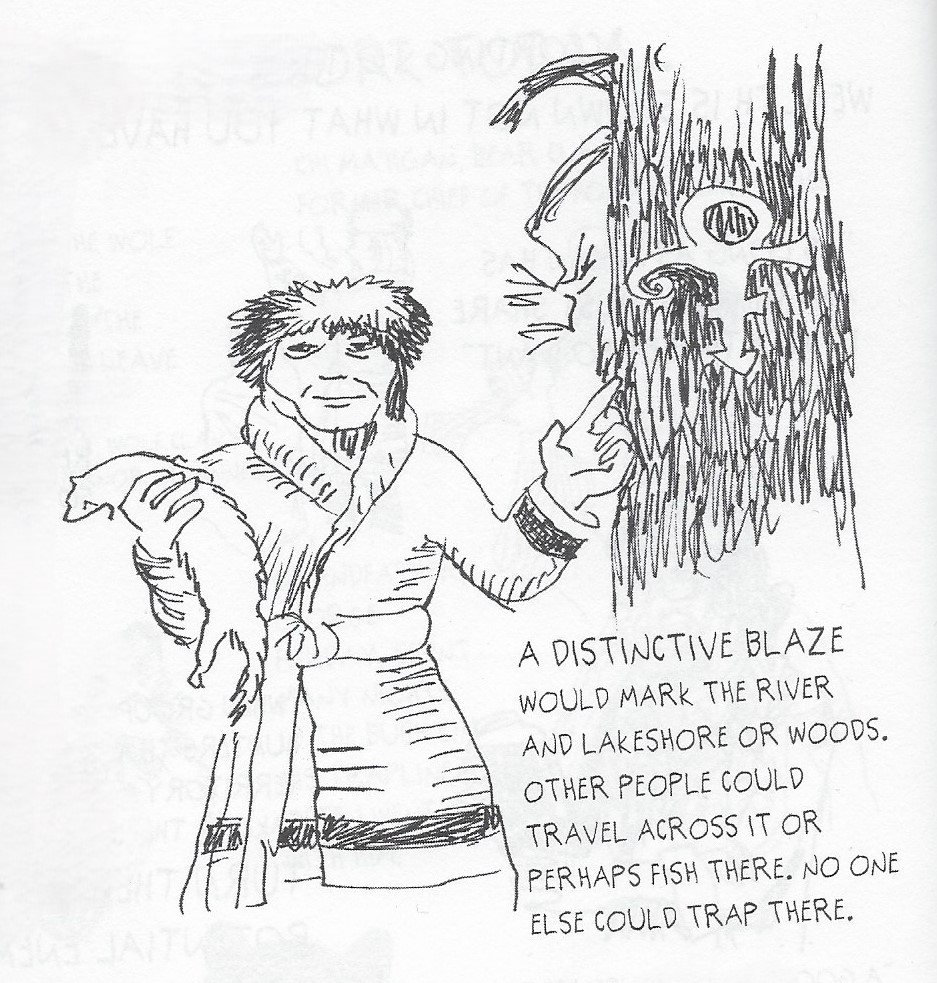

To do this, Gawboy draws from hands-on knowledge about the tools and technology of the fur trade, including step-by-step birch bark canoe building, working with animal hides and even the old way of snaring a rabbit for the soup pot.

But as Gawboy clarifies, “it’s not a technical guide. It’s just to show how much work it is. You just can’t say the Ojibwe made birch bark canoes. I wanted to show how much work there was in putting one together.”

A lot of what he writes about in the book comes from first-hand experience growing up in the woods around Ely, Minnesota.

“All the men folk that I knew had trap lines,” said Gawboy. “And so just listening to their stories, and just growing up there made me want to be a trapper too. And by the time I was in high school, some friends and I actually did some trapping. I have to confess that I wasn’t a very good trapper, but I had the experience of going out and checking the traps.”

The cultural and economic realities of the fur trade from the standpoint of his Ojibwe ancestors became apparent when Gawboy was studying American Indian history in college and preparing for his career as an Indian Studies teacher.

That was when Gawboy realized: “something’s been missing from the way the fur trade has been talked about. And so, I decided to teach a course in the history of the fur trade, because I came to conclusion that that, doggone it, the fur trade is our history, and it’s not being taught that way.”

Not Afraid to Love

Original illustrations by Carl Gawboy, courtesy of Animikii Mazina’iganan: Thunderbird Press, Fond du Lac Tribal and Community College, 2024

Throughout the book, Carl literally draws himself into the story as historical explainer, through the voice of his illustrated avatar, which speaks to the reader while gesturing with a pointer at important historical facts or key connections. It was his own classroom research, drawn out on 3×5 cards and compiled over many years, that became the basis of the book.

In addition to filling in the gaps of fur trade history, Gawboy graces the reader with hand-drawn blocks of text and poetry, revealing the author’s own generosity of spirit, as well as the generosity of Ojibwe people. Like this poem which appears on the back cover:

We clothed the Royals.

We fed the worker.

We guided the traveler.

We abetted the soldier.

We are not afraid to love.

I asked Mr. Gawboy about this declaration — about the love and generosity of Ojibwe people.

“Well, first of all, teaching in Indian Studies, I realized that the Ojibwe are different from everybody else,” said Gawboy. “I mean, we think differently. Our history is different. How we did things are really different. And many Ojibwe people like to say how similar they are to other Indians. I think it’s because Ojibwe people go to school together with other Indian tribes. They travel a lot.”

He continued: “So, I wanted to emphasize that point in the book — that the way we did things were different from say, the Lakota — our next-door neighbors from across the prairies. The Lakota wanted to control the fur trade, but they only allowed one or two fur traders into their country, and that was different. It’s not that they didn’t like fur trade goods. They liked beads and iron kettles — but one of the things that they really hated was trespassers. And of course, that ran into all kinds of trouble ever since the Louis and Clark Expedition and the Indian Wars. ‘You don’t come on our territory, and if you do, we’ll get you.’ The Ojibwe aren’t like that. When new strangers came to our part of the country, they said, ‘Okay, what do you want? Let’s see if we can work out a trade system. Let’s see who can come up with some agreements, and, hey, do you like furs? We got a lot of them.’ So, it was just a different way of dealing with it. That means our history ended up differently. We didn’t end up in a genocidal war against the Americans, for example.”

Fur Trade Jokes and Power Couples

Original illustrations by Carl Gawboy, courtesy of Animikii Mazina’iganan: Thunderbird Press, Fond du Lac Tribal and Community College, 2024

One of the joyful elements that readers might find throughout Fur Trade Nation are many well-placed laughs, and what Gawboy calls “fur trade jokes.” The Land O’ Lakes butter maiden makes an appearance and even “his purple highness” a.k.a. Prince gets a nod.

“Those fur trade jokes were real jokes,” said Gawboy. “That one cartoon where the Governor General of Canada comes to Rat Portage (along the fur trade route), and tells the local trader that he’d like ‘to meet a real Indian.’ So, the fur trader looks around . . .then an Indian comes walking by and he says, ‘McDonald, would you come over here for a minute?’”

Mr. Gawboy points out that not everyone will get the joke.

“I showed that cartoon to whites on the faculty at Fond du Lac Community College and to Indians at the college, and the Indians laughed and laughed, and the whites just stared — they wouldn’t get it,” said Gawboy. “The joke, to me, is that so many Indians have Scottish names, French names . . .and these marriages go back generations and generations. The French and Scottish fur traders were interested in having surnames, so they wanted their kids to carry their name.”

Today, many Ojibwe families still carry French or Scottish surnames.

Gawboy also includes several “power couples” of the fur trade era, such as Madeline and Joseph LaFamboise. After Joseph was murdered in 1806, his Odawa wife Madeline continued on as a trader.

“She amassed a great fortune and was eventually bought out by John Jacob Aster of the American Fur Company,” said Gawboy.

This led me to ask about Ojibwe women’s contributions to the fur trade.

“Women were in charge of trading, and a lot of the white traders didn’t like it because they wouldn’t get as good a deal, like they would when dealing with the men,” said Gawboy. “That’s pretty interesting. It means that the women were very, very canny traders.”

Another example of how Ojibwe women shaped fur trade history requires an adjustment from how the mainstream historical record has classified Ojibwe people.

“If you talk to most Ojibwe people today, they say, ‘Oh, we were hunters and gatherers. We weren’t farmers,’” said Gawboy. “And when you actually look at the history, the Ojibwe were real good farmers. They developed new strains of corn that grew in northern regions — short season varieties.”

Gawboy uses the example of Garden River Ontario, where there were vast fields of corn crops. He also points out the old descriptions of Madeline Island on Lake Superior as corn growing country. According to Gawboy, those were Ojibwe people growing all that corn, and Ojibwe women specifically. He says that the inaccurate historical narrative about these places connects back to control of the land.

As Gawboy elaborates: “The reason why anthropology decided to call all Ojibwe ‘hunters and gatherers’ was because it was a lot easier to colonize them, you know, make them move to reservations. Because how many times have you heard: ‘They weren’t using the land.’ But they were. They were using it like crazy. But see, you label somebody long enough they start believing it.”

The book also connects the continuum of fur trade history to the art and lives of modern Indigenous people — even tracing the origins of glass beads as a hot commodity, then and now.

“So many Ojibwe artists talk about the history of what they do, whether they’re beadworkers or ribbon skirt makers,” said Gawboy. “I wanted to show how both contemporary artists and their contribution to the art world, connects them to the to the fur trade of the 1700s and the 1800s. It’s a continuous flow. It’s not like a revival or a rediscovery. It’s continuous. It just never stopped.”

Fur Trade Nation makes it clear that without the technology, skills, generosity and yes, love of Ojibwe/Anishinaabe people, the world’s economic engine wouldn’t have happened in the same way — or maybe not at all.

“That’s my belief,” echoed Gawboy.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Ojibwemodaa! Let’s speak Ojibwe!

A Symbol of Survival: Red Pine Peels and Ojibwe Canoe Factories

Featured image: Original illustrations by Carl Gawboy, courtesy of Animikii Mazina’iganan: Thunderbird Press, Fond du Lac Tribal and Community College, 2024