I Speak for the Fish is a monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor Kathy Johnson, coming out the third Monday of each month. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit PBS. Check out her previous columns.

I Speak for the Fish is a monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor Kathy Johnson, coming out the third Monday of each month. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit PBS. Check out her previous columns.

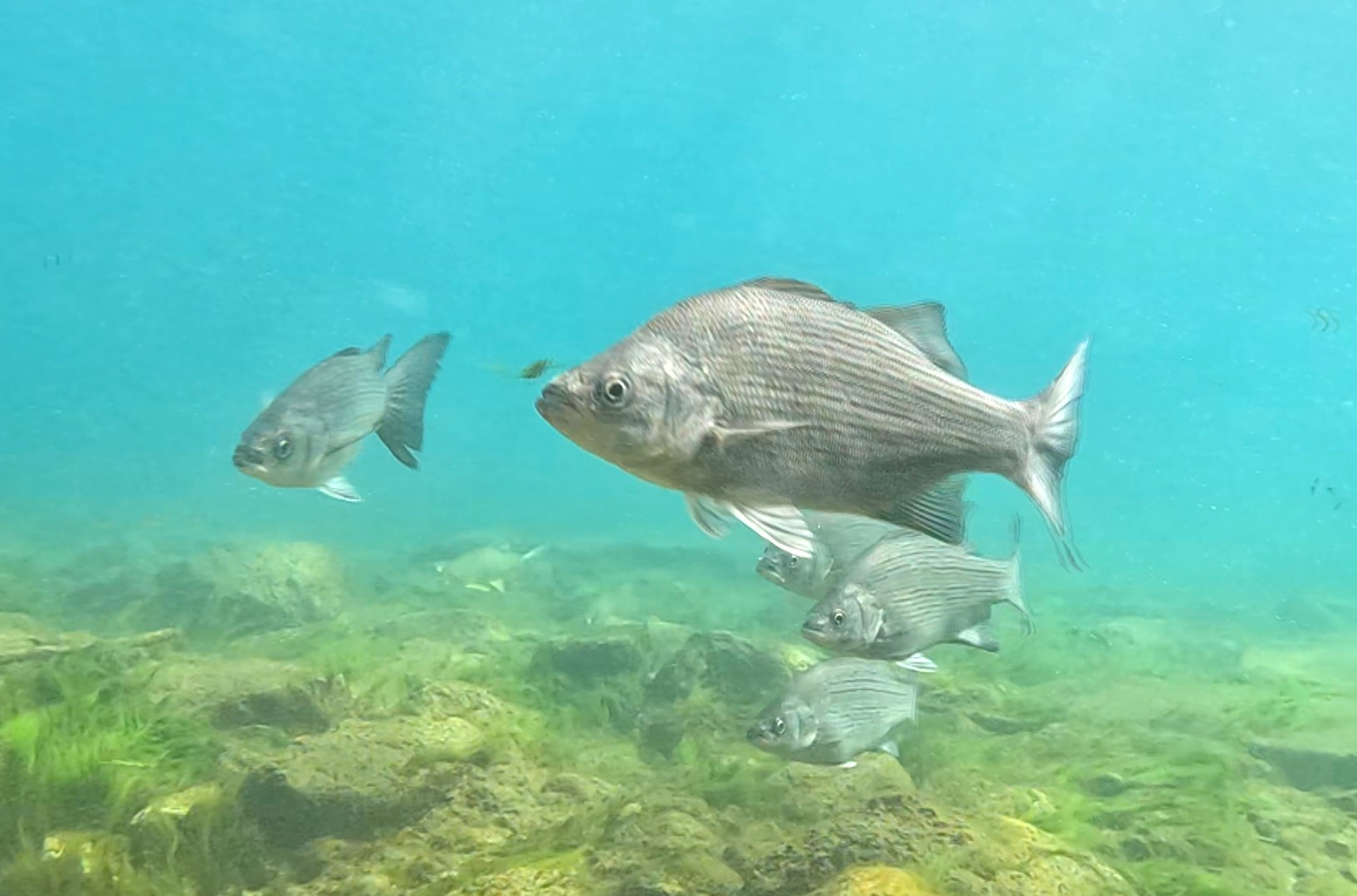

They hunt at dusk and dawn. Rising out of the depths in small packs, they move with speed and strike with deadly force.

Their sterling bodies are not armor-plated with large scales, rather they look as smooth and shiny as a lightly used piece of aluminum foil. The stippled-black stripes on their sides are far more obvious in my field guides than when they swim past me.

They are the quintessential shape that most people picture when they hear the word fish. Not too rotund. Not too elongated. Perfectly, classically fish-shaped.

They are skilled predators that hunt in synchronized packs. They are elusive, and to my cameraman husband’s chagrin, more cautious than curious.

They are known by many names: sand bass, silver bass, striped bass, striper, stripe, and white lightning.

They are white bass, one of the only true bass species in the Great Lakes.

Who you calling a Bass?

Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch

Earlier this year, I opened the bass section of my favorite field guide to read up on rock bass. Except they are in the sunfish section. I should have remembered that since rock bass look and act very much like oversized bluegills.

However, I struggled to see why smallmouth and largemouth bass were also in the sunfish section.

I called up retired Michigan Department of Natural Resources fisheries biologist, Mike Thomas, for clarification.

Scientists consider various factors when grouping fish, including body shape and bone structure, their preferred habitat, what and how they eat, how they reproduce, similarities in their genetic family tree, etc.

There are two types of bass in the Great Lakes: black and true, or temperate.

Black bass, which includes rock, smallmouth, and largemouth, are grouped under the sunfish family. This is because of certain similarities, such as how they build and guard nest sites and their overall preference for shallower water.

Black bass are only found in freshwater and they belong to the Centrarchidae family.

True or temperate bass are open-water fish found in both fresh and saltwater habitats. True bass do not build nests or provide any parental care. They are big water fish that belong to the Moronidae family.

White bass are true bass. They like clear water, firm bottoms, and places with plenty of small fish to eat.

Leader of the Pack

Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch

Regular readers may have noticed that I’ve done a series of canine analogies in my bass columns this year.

I’ve described how the playful nature of rock bass reminds me of 10-month-old golden retrievers and why smallmouths strike me more as 3-year-old military-trained German Shepherds.

The elusive nature. The predatory intensity from their yellow eyes. The need for big wide-open spaces. The deadly dusk and dawn teamwork. In white bass, I see freshwater wolves.

White bass are predators, and more specifically, piscivores, meaning the adults feed almost exclusively on other fish. Minnows, shad, yellow perch, sunfish, and even their own young are all menu options.

They typically target schooling fish rather than bottom-dwellers, such as log perch and darters.

White bass prefer open water but will pursue baitfish wherever they go, including water only a few feet deep. We’ve witnessed this on many occasions when sitting on shore.

Without warning, the surface of the water nearshore will suddenly erupt as thousands of baitfish jump into the air. With nowhere left to run the little fish leap for their lives.

It’s not easy being the tiny fish that everybody targets.

Many marine species also force baitfish to the surface for easier feeding. For instance, humpback whales work together to create bubble rings to trap small fish and krill at the surface. In the Great Lakes, white bass are the only ones who work together to corner baitfish

So, when hundreds of tiny fish suddenly burst from the surface of Lake Huron, it’s almost a guarantee that there is a hunting pack of white bass below.

Females grow faster and live longer than males. Although white bass can survive 10 to 15 years in the wild, most will not make it past age 4.

Historical records from the early to mid-1800s note the greater part of the commercial fishing catch in Western Lake Erie consisted of white bass. The fish appeared in “enormous schools” and were so plentiful that 100 pounds sold for just six and a half cents.

In the wasteful manner of the time, it was not uncommon for tons of white bass to be thrown overboard daily in the lack of a purchaser. By the mid-1900s, when “The Fishes of Ohio” author Milton Trautman was fishing Menominee Bay, he found white bass to be “almost entirely absent.”

Thankfully, white bass are still found from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico. Given the assault on their numbers and their total lack of parental care, I think it’s remarkable that any have survived.

Latchkey babies

Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch

It’s not uncommon for male fish to reach their spawning grounds before the ripe females. Male lake sturgeons normally arrive 3-4 days ahead of the females, but white bass males set the record by arriving up to an entire month ahead!

One of the reasons smallmouth and other black bass are grouped with sunfish is because they all build nests on the bottom. Being a true bass, white bass spawn at the surface. The spawning activity begins when the females arrive and the water temperature reaches about 57 degrees Fahrenheit.

I have never seen white bass spawning, but my tattered copy of “Thompson’s Guide to Freshwater Fishes” has a great description.

“As the females arrive on the spawning grounds, the schools remain separated according to sex, with the females holding in deeper water. To begin the spawning act, a female will rise toward the surface… This rise will attract several males, which will crowd around her as the eggs and sperm are simultaneously released.”

The fertilized eggs sink to the bottom. Like many fish eggs, they are sticky and stay wherever they land. The lack of protection from predators may account for their amazingly short incubation period. The eggs hatch in just two days!

I find that remarkable considering muskies spawn in a similar fashion and their eggs take two weeks to hatch, while northern madtom eggs can take a month to hatch.

The white bass hatchlings grow quickly but as is the way with fish, the threat of being eaten by bigger fish will continue for most of their lives.

I’ve never dived at dawn and I rarely dive at dusk. I typically dive during the day or well after dark on night dives. So, while there are a lot of white bass in my area, I don’t usually see them.

One of the highlights of the underwater livestream that we launched last summer is getting to see white bass almost every night. Underwater lights installed with the camera allow for nocturnal viewing until 10 p.m. EST each evening.

They appear at twilight.

Tight formations of five or six moving in perfect unison. A synchronized pack. The underwater lights bounce off their metallic bodies as they move across my screen. A few bright flashes of silver and then they are gone.

Featured image: White bass. (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)