This story is a part of “A Year in the Wild Kitchen of the Great Lakes,” a series in partnership with expert forager Lisa M. Rose with the mission of nurturing a deeper connection with the natural world through foraging. To get started with your foraging journey, begin here with our “Framework to Sustainable and Safe Practices.”

Foraging encourages sustainability and promotes a deeper understanding of ecological balance by fostering a relationship with local ecosystems. By blending the old with the new — traditional recipes with wild, foraged foods — we not only preserve our culinary heritage but also embrace a sustainable approach to eating and land conservation that honors both our past and our planet and our collective future. Read on to learn more about my Cornish ancestry and how I’ve given the Up North Pasty recipe a new twist with the wild, foraged flavors of the stinging nettle.

Cornish Culinary Heritage in Calumet, MI

Cornish immigrants played a significant role in the mining history of Calumet, Michigan, during the copper boom of the 19th century. Their migration primarily started in the 1840s and continued well into the late 19th century.

Cornish miners were highly sought after for their mining skills, particularly in hard-rock mining techniques, which were essential for the copper-rich but challenging geological formations of the Keweenaw Peninsula.

They brought with them expertise in high-risk areas of mining, including blasting and tunneling in deep underground shafts. Their knowledge in constructing and managing engine houses for steam-powered pumps, which were critical in keeping the deep mines dry, was also invaluable.

Cornish come to Calumet

Cornwall, located in the southwest of England, was a renowned center for tin and copper mining, but by the mid-1800s, these industries began to decline due to exhausted ore deposits and competition from abroad.

At the same time, the discovery of vast copper deposits in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula offered new opportunities. The region’s need for experienced miners coincided with the economic hardships faced in Cornwall, prompting many Cornish miners, known as “Cousin Jacks,” to migrate to areas across the world with more prosperous mining opportunities.

My own family of Cousin Jacks and Cousin Jennys first immigrated to Calumet from Cornwall in 1864. My 3rd great grandfather, William James Downing arrived from Cornwall to Calumet, originally leaving his wife and children behind to seek out more prosperous mining opportunities than what the mines of Cornwall could provide.

The Downing family home in Constantine, Cornwall around 1870. (Photo courtesy of Lisa M. Rose)

By 1870, William James had enough money and sent for his wife, Caroline and their three children to join him in Calumet. While life in Calumet for a miner was tough, the move to the United States gave them considerable more opportunity and made way for a better life for their family and subsequent generations.

The Downing & George family shoreside in the Keewenaw, circa 1910. (Photo courtesy of Lisa M. Rose)

The Cornish Kitchen

Aside from their technical contributions, Cornish immigrants also had a profound cultural impact. They introduced the Cornish pasty (pronounced past-ee) to the region, a hearty, easy-to-carry meal ideally suited for miners’ long, labor-intensive days underground. This culinary tradition has remained a beloved staple in the area to this day.

The Pasty

The Cornish pasty is a traditional food from Cornwall, England, deeply rooted in the region’s mining heritage. Its origins trace back to the 17th and 18th centuries, gaining popularity as a practical meal for miners.

The pasty’s design — with its thick, crimped crust forming a natural handle — allowed miners to eat it with dirty hands without contaminating the filling. This crust was often discarded after eating to avoid consuming the arsenic and other toxins present from handling ores.

Preparing the pasty: The pasty has crimped edges which once allowed the miners to hold the pasty by the crust – which would then be discarded to avoid ingesting hazardous materials the miners often handled while below ground. (Photo Credit: Lisa M. Rose)

Cornish pasties were not only practical but also nutritious, filled with meat, potatoes, and vegetables — all ingredients that could sustain a miner through long hours underground. As Cornish miners emigrated to various parts of the world, including the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, they brought their pasty-making skills with them, embedding this culinary tradition into the local culture of mining communities globally.

Crafting the Nettle Pasty: A Culinary Fusion

Lisa M. Rose, sharing her wild and foraged pasty recipe in the kitchen, as generations of her Cornish ancestors did when arriving from Cornwall in the late 1800s. (Photo Credit: Nigel J. Young)

The pasty is particularly important to me because of my family’s Cornish roots. My mother would make dozens at a time and prepare them for the freezer – an effort of love that fed our family well when budgets were lean during the trying economic times of the 1980s.

While I wasn’t able to fully appreciate the pasty as a child (admittedly they were quite bland for my own preferences, and would douse them in mustard), I’ve come to embrace the symbolism of the food as a one of resilience, nourishment, hard work, family, and love.

To that end, and inspired by the rugged spirit of those Cornish miners and the lush landscape of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, I decided to blend tradition with local foraging to create the Nettle Pasty. This recipe infuses the hearty, comforting Cornish pasty with the wild, earthy flavor of nettles, picked from the very same land that those miners walked.

Nettles ready to be transformed into the Wild Nettle Pasty. (Photo Credit: Lisa M. Rose)

Why nettles?

Gathering Nettles Creekside. (Photo Credit: Nigel J. Young)

If you’re fond of spinach, nettles might just become your new favorite green. Known scientifically as Urtica dioica, these plants are not only packed with nutrients but also boast a rich, spinach-like flavor that makes them perfect for culinary use. From pizzas and pastas to egg scrambles, nettles add a nutritious twist to various dishes, offering more minerals and plant protein than their leafy counterparts.

Nettles thrive in nitrogen-rich, damp soils and can often be found in areas adjacent to water bodies. They demand respect; their fine, hollow hairs release formic acid upon contact, causing a stinging sensation reminiscent of rubbing against fiberglass. But fear not — this sting is neutralized when the nettle is cooked, and its nutritious potential is unleashed.

Nettle is a perennial, deep green plant that reaches heights of 7 feet in rich, nutrient-dense soil. Its opposite leaves are oblong, dark green on top and lighter green underneath, covered in fuzzy hairs, and roughly toothed and deeply veined. One of nettle’s chief identifiers is its sting. Stinging nettle doesn’t really have stingers or thorns, but instead has fine, hollow hairs filled with formic acid that break open on the skin.

When and Where to Forage for Nettles

Nettles ready to be transformed into the Wild Nettle Pasty. (Photo Credit: Lisa M. Rose)

The best times to go nettle-hunting are in the mild weather of spring (April to June) and the crisp days of late fall (October to November). Look for these hardy plants in nitrogen-rich, damp, well-drained soils — often near rivers, streams, lakes, or moist woodland areas.

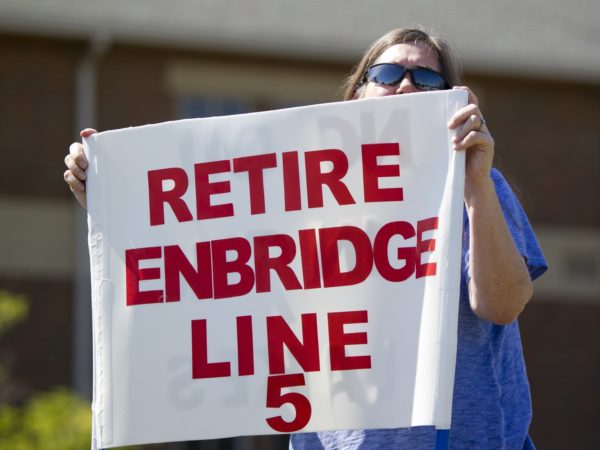

Because nettles will take up minerals and contaminants in surrounding soil avoid gathering nettles on or downstream from an immediate area that was used as a mine or mine processing area. For more information on safe and sustainable foraging visit my column, Your Foraging Journey: A Framework to Sustainable and Safe Practices.

How to Harvest Nettles

When gathering nettles, gear up with harvesting gloves to shield yourself from their sting. Opt for the young, tender leaves and stems early in the season for the best flavor and texture. Nettles can grow quite tall, but the ideal length for collecting is about 18 inches, perfect for bundling and drying. Whether you’re drying, freezing, or using them fresh, nettles are incredibly versatile in the kitchen.

Beyond Food: Foraging Helps Heal the Land

In regions like Calumet, Michigan, which have a legacy of industrial mining, the use of foraged ingredients and the practice of foraging can be particularly beneficial for environmental restoration for several reasons:

- Awareness of Contaminants: Foraging requires knowledge of the local environment, including understanding areas that may be contaminated by industrial residues such as heavy metals. This awareness can prompt foragers and the community to advocate for and participate in cleanup efforts. Foragers can act as environmental stewards, monitoring the land and identifying areas where soil and water might be contaminated and thus prioritizing them for restoration efforts.

- Phytoremediation: Certain plants are known for their ability to extract and stabilize heavy metals and other contaminants from the soil, a process known as phytoremediation. By strategically foraging and promoting the growth of these plants in contaminated areas, the community can engage in a natural form of land rehabilitation. This not only helps in cleaning up toxic residues from mining but also prepares the land for other uses in the future.

- Promoting Native Plant Growth: Foraging that focuses on native plants can boost their growth, which in turn can help out-compete invasive species that might otherwise take over areas disturbed by mining activities. Native plants are crucial for maintaining local biodiversity and can contribute to the overall health of ecosystems, which is vital for habitats that have been degraded through industrial activities.

- Community Involvement and Education: Engaging the local community through foraging activities can enhance public understanding of ecological issues and the importance of land and water stewardship. This can lead to increased community-led conservation efforts, including cleanups, planting native species, and other restoration activities. Educating the public about the environmental impact of mining and the potential for natural restoration can foster a collective responsibility towards the local environment.

- Economic Alternatives: Encouraging foraging and the use of foraged ingredients can also provide economic benefits, such as the development of local markets for foraged goods or eco-tourism related to natural and historical heritage. These economic opportunities can offer sustainable alternatives to industries that cause environmental degradation, promoting a more balanced approach to local development.

In Calumet and similar areas, integrating foraging into the community’s lifestyle not only contributes to ecological restoration but also helps in rebuilding a healthy, sustainable relationship between the residents and their natural environment, turning the scars left by industrial activities into opportunities for growth and renewal.

Recipe: Foraged, Wild Nettle Cornish Pasty from Michigan’s Copper Country

Nettles ready to be transformed into the Wild Nettle Pasty. (Photo Credit: Lisa M. Rose)

Inspired by the resilience of my Cornish mining ancestors and the verdant wilderness of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, I created this Wild Nettle Pasty. This innovative recipe infuses the traditional Cornish pasty with sautéed wild nettles, offering a taste that is both robust and nuanced. The nettles are prepared with care, sautéed with onions and garlic to unlock their flavors before being enveloped in a flaky, buttery pastry alongside hearty fillings of beef, potatoes, and rutabaga.

Begin with preparing the nettles — sautéed gently with onions and garlic to enhance their flavor. The pastry is simple, yet it holds the robust filling of beef, vegetables, and nettles perfectly. Baking transforms these ingredients into a golden, flaky pasty that is both a nod to the past and a celebration of the present.

Ingredients:

- For the Pastry:

- 4 cups plain flour

- 1/2 cup lard or unsalted butter, chilled and diced

- 1/2 cup vegetable shortening, chilled and diced

- 6-8 tbsp cold water

- Pinch of salt

- For the Filling:

- 2/3 lb skirt steak or beef chuck, finely chopped (or portobello mushrooms)

- 1 cup potato, diced small

- 3/4 cup rutabaga, diced small

- 1 large onion, finely chopped (divided use)

- 2 cloves garlic, minced

- 1 packed cup wild nettles, roughly chopped (use gloves to handle)

- 2 tablespoons butter

- Salt and pepper to taste

- A knob of butter (optional, to top each pasty)

Instructions:

- Prepare the Nettles:

- Handling: Wearing gloves, rinse the nettles thoroughly to remove any dirt or bugs. Roughly chop the nettles while still wearing gloves to avoid stings.

- Sautéing: In a skillet, melt 2 tablespoons of butter. Add half of the chopped onion and the minced garlic, sautéing until they start to become translucent. Add the chopped nettles to the skillet. Cook over medium heat, stirring frequently, until the nettles are wilted and tender, about 5-7 minutes. Remove from heat and let cool.

- Prepare the Pastry:

- In a large bowl, sift the flour and salt together. Add the chilled lard and vegetable shortening.

- Rub the fats into the flour using your fingertips until the mixture resembles coarse breadcrumbs.

- Gradually add cold water, mixing until the dough comes together. Form into a ball, wrap in cling film, and chill for about 30 minutes.

- Prepare the Filling:

- In a large mixing bowl, combine the sautéed nettle mixture, chopped beef, remaining onion, potatoes, and rutabaga. Season well with salt and pepper. Mix thoroughly to ensure the flavors are well distributed.

- Assemble the Pasties:

- Preheat your oven to 425°F.

- Roll out the chilled dough on a lightly floured surface to about 1/4 inch thickness. Cut out rounds using a plate or large cutter (about 20 cm diameter).

- Spoon a generous portion of the filling onto one half of each pastry round. Place a small knob of butter on top of the filling if using.

- Brush the edges of the pastry with water, then fold the pastry over the filling to form a semi-circle. Press the edges together firmly.

- Crimp the edges by pinching and folding the pastry to seal in the filling completely.

- Make a small slit in the top of each pasty to allow steam to escape during baking.

- Bake the Pasties:

- Place the pasties on a baking sheet lined with parchment paper.

- Bake in the preheated oven for 20 minutes, then reduce the temperature to 350°F and bake for another 40 minutes until golden and cooked through.

About the Author

Lisa M. Rose is an ethnobotanist, wild foods chef, and author with a profound dedication to exploring the symbiotic relationship between humans and plants. With an academic background in anthropology and community health, her culinary journey has been rich and varied, including stints with notable establishments and figures such as Stags Leap in Napa Valley, Alice Waters’ The Edible Schoolyard, and organic farmers in Northern Michigan.

Rose’s work is celebrated in her bestselling books, “Midwest Foraging” and “Midwest Medicinal Plants,” among others and her expertise is frequently sought by major media outlets, including the Chicago Tribune, PBS, NPR, Martha Stewart and CNN.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Foraging’s Spring Backyard Splendor: Dandelions and Violets

A Fleeting Wild Taste of Spring Ephemerals: Ramps and Ostrich Fern

Featured image: Lisa M. Rose, foraging wild nettles for her wild nettle pasty recipe. (Photo Credit: Nigel J. Young)