By Michael Livingston, Interlochen Public Radio

Points North is a biweekly podcast about the land, water and inhabitants of the Great Lakes.

This episode was shared here with permission from Interlochen Public Radio.

October 15, 1900 was a dark day for a small group of Native Americans near the tip of Michigan’s lower peninsula. It’s the day a group of white men burned their village to the ground, leaving many families homeless.

It’s also the event that led to the Burt Lake Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians losing their identity in the eyes of the federal government.

For more than a century, the Band has been trying to get that recognition back. Federal recognition unlocks money for healthcare, education, and the preservation of culture and history. But the odds aren’t stacked in their favor.

CREDITS:

Producer: Michael Livingston

Host: Daniel Wanschura

Editor: Morgan Springer

Additional Editing: Ellie Katz, Dan Wanschura

Music: Slimheart, Four Count, Dusky, At Our Ease, Tapoco Critter, Tessie’s Ranch by Blue Dot Sessions

TRANSCRIPT:

DAN WANSCHURA, HOST: About a dozen men set off from the town of Cheboygan, Michigan. They were armed – some on foot, others on horseback. They were heading southwest toward a place they called Indian Village. A greasy smell was trailing them. They carried buckets of cheap and flammable kerosene – it was typically used for lighting lamps at the time.

But not that day, October 15, 1900.

The village, where these men were heading, it was the home of the Cheboiganing Band – now called the Burt Lake Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians.

On that day, the men of the Cheboiganing Band were walking to town where they were picking up their paychecks. Most of them worked for nearby lumber mills.

The women, children and elders would have been carrying out their day like it was any other. Their village was on a small peninsula on Burt Lake. A beautiful, peaceful place surrounded by white birches and maple trees.

At about two in the afternoon, the white men from Cheboygan arrived and hid in the woods nearby the village.

There were 20 cabins, several barns, a Catholic Church, places for livestock and space for farming.

They waited with their torches and rifles until they thought the time was right. Then, one of the men approached the cabins and read from an official-looking piece of paper. It said the local court had ordered all the villagers to clear out – now.

The people may have refused at that moment, but it wouldn’t have mattered. That afternoon, the Cheboygan men went from cabin to cabin chasing people out.

The residents could only gather what they could carry – maybe some tools, blankets or clothes.

The men doused the cabins with the kerosene, struck a torch and burned the settlement to the ground. Nearly eight centuries of native residency went up in flames.

Dusk fell, some Cheboygan men rode off and it began to rain. The Native American men returned and took their families away from the smoldering ruins. On that day in 1900, they didn’t just lose their village, this land is their identity in many ways and they vowed to get justice.

At the crux of it all was something complicated. They had to prove they existed in the eyes of federal officials.

NOLA PARKEY: We believe that we are a federally recognized tribe… You almost want to grab somebody and shake them and say, can’t you understand this?

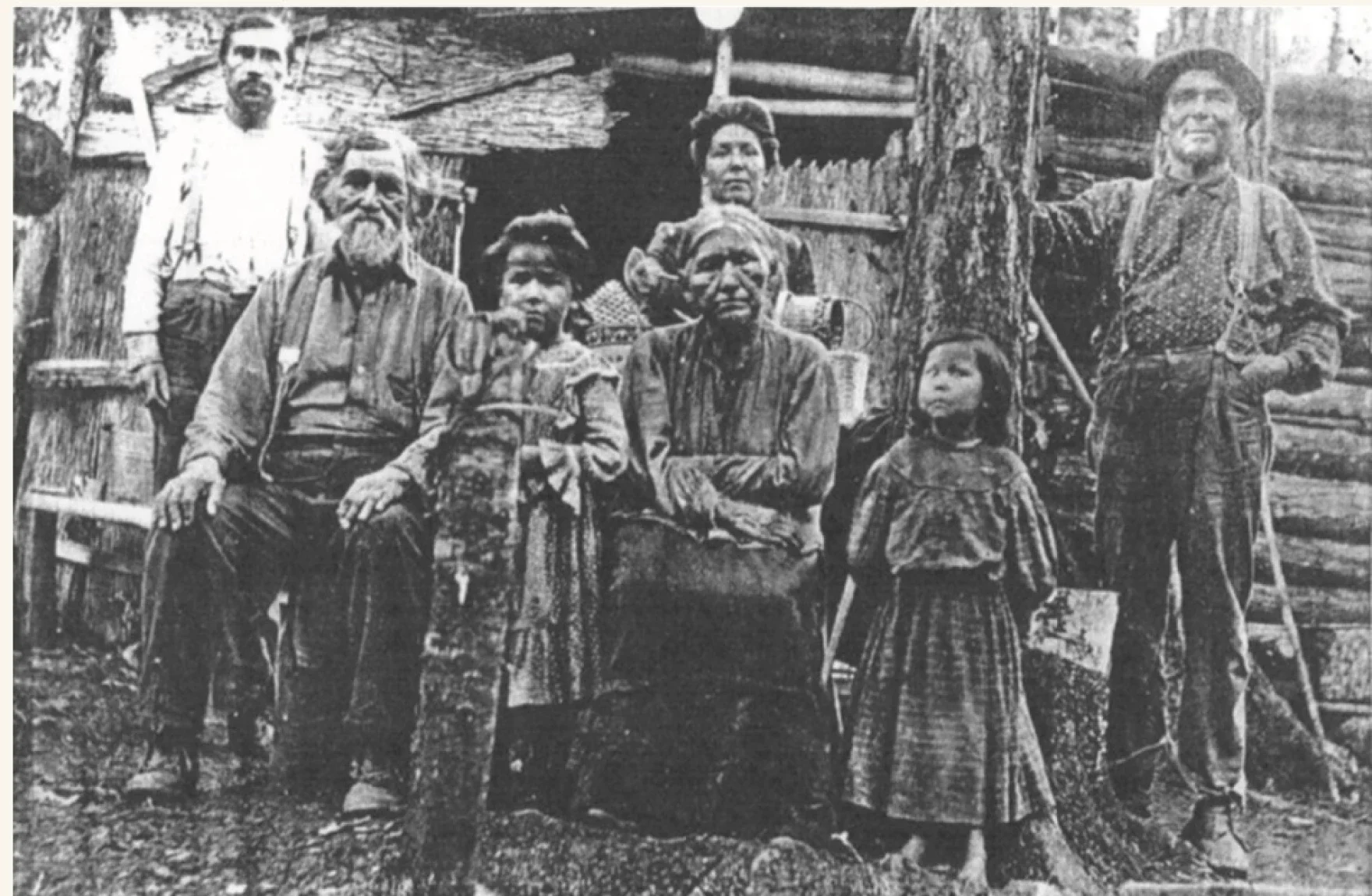

Parts of three families pictured here were forced to abandon their homes in Burt Lake, prodded by men of Cheboygan County on Oct. 15, 1900. Back row: Albert Shenonquet, Mrs. Albert Shenonquet,, Frank Shenonquet. Front row: Antwine Shenonquet, Cora Shenonquet, Mrs. Antwine Shenonquet and Josephine Shenoskey (credit: Burt Lake Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians)

WANSCHURA: This is Points North, a podcast about the land, water and inhabitants of the Great Lakes. I’m Dan Wanshura. Today, the story of everything that happened after the Burt Lake Band was burned off their land. And their fight for justice. Reporter Michael Livingston picks up the story right after this.

MICHAEL LIVINGSTON, BYLINE: News of the village burnout traveled fast, but it wasn’t always sympathetic. That week, an article was published in the Cheboygan Democrat Newspaper titled “Lo! The Poor Indian.”

It uses a slur and says, “…the Indians, from the old down to the children, sat and watched the burning of what had been their homes and at last realized the seriousness of the law of the white man.”

In this case, the white man was John McGinn, a local banker and land speculator.

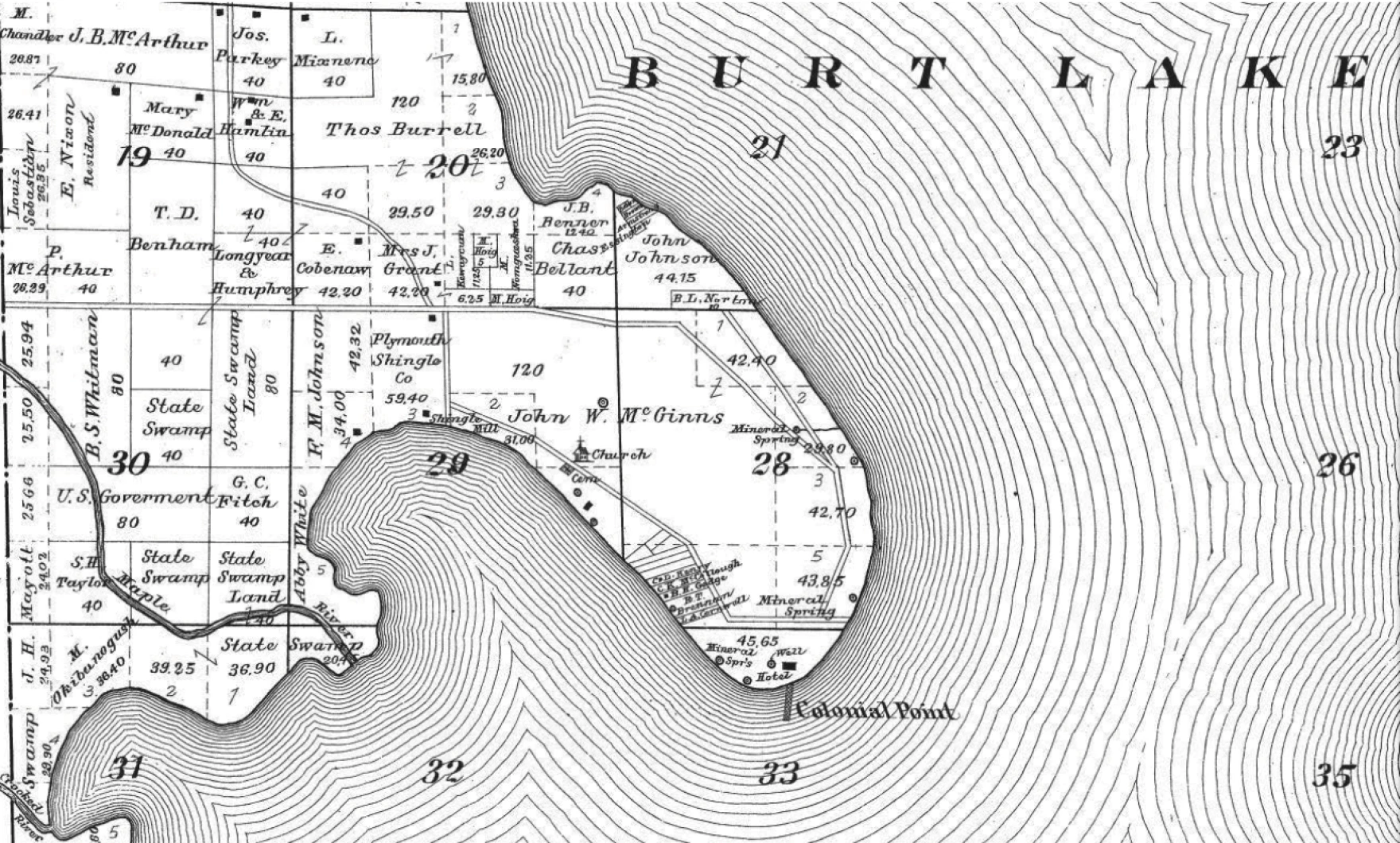

Even then, the inland lakes of Cheboygan County were high-value real estate. And John McGinn wanted that land, specifically on that Burt Lake peninsula.

He had a problem though. The Burt Lake Band were signatories of the 1836 Treaty of Washington. This treaty recognized the tribe and gave them reservation land and other benefits.

The peninsula on Burt Lake where their village stood, belonged to them.

On top of that, the Band had purchased the peninsula – 375 acres – and placed it in the trust of the state. They thought it was double assurance that no one could take their home.

But that move was John McGinn’s in. And it all came down to taxes. Because the land had been purchased, local officials became confused. Should the property be taxed or not? Some years it was taxed, other years it wasn’t. It all depended on who was in office at the time.

John McGinn seized on that inconsistency and went to the local court.

While the Band understood the land could not be taxed because it is a sovereign nation – McGinn argued the families in Indian Village had dodged paying taxes for years. And the local court agreed with him.

And so, John McGinn began buying up the delinquent tax titles without the Band’s knowledge. He bought title after title until that day, October 15, 1900 when he and the other Cheboygan men burned down the village.

Immediately after they were chased away – most of the villagers took shelter with nearby friends and family. Others may have traveled farther and moved in with other tribes in the Great Lakes region.

It was around this time too, native children were sent off to residential boarding schools where they were punished for practicing native culture, religion and language.

Ken Parkey, a Burt Lake Band elder, remembers how his family was taken to these schools.

KEN PARKEY: My dad got taken to Holy Childhood, my dad and my uncle.

LIVINGSTON: Holy Childhood was a boarding school about 15 miles away from Burt Lake. Ken says it was so bad, his dad and uncle tried to run away. But the priest found them back near Burt Lake.

KEN PARKEY: So, what they done, is send my dad and my uncle to Mount Pleasant boarding school. Got ‘er down there and figured it’s to god-darn hard to run away from that school, you know.

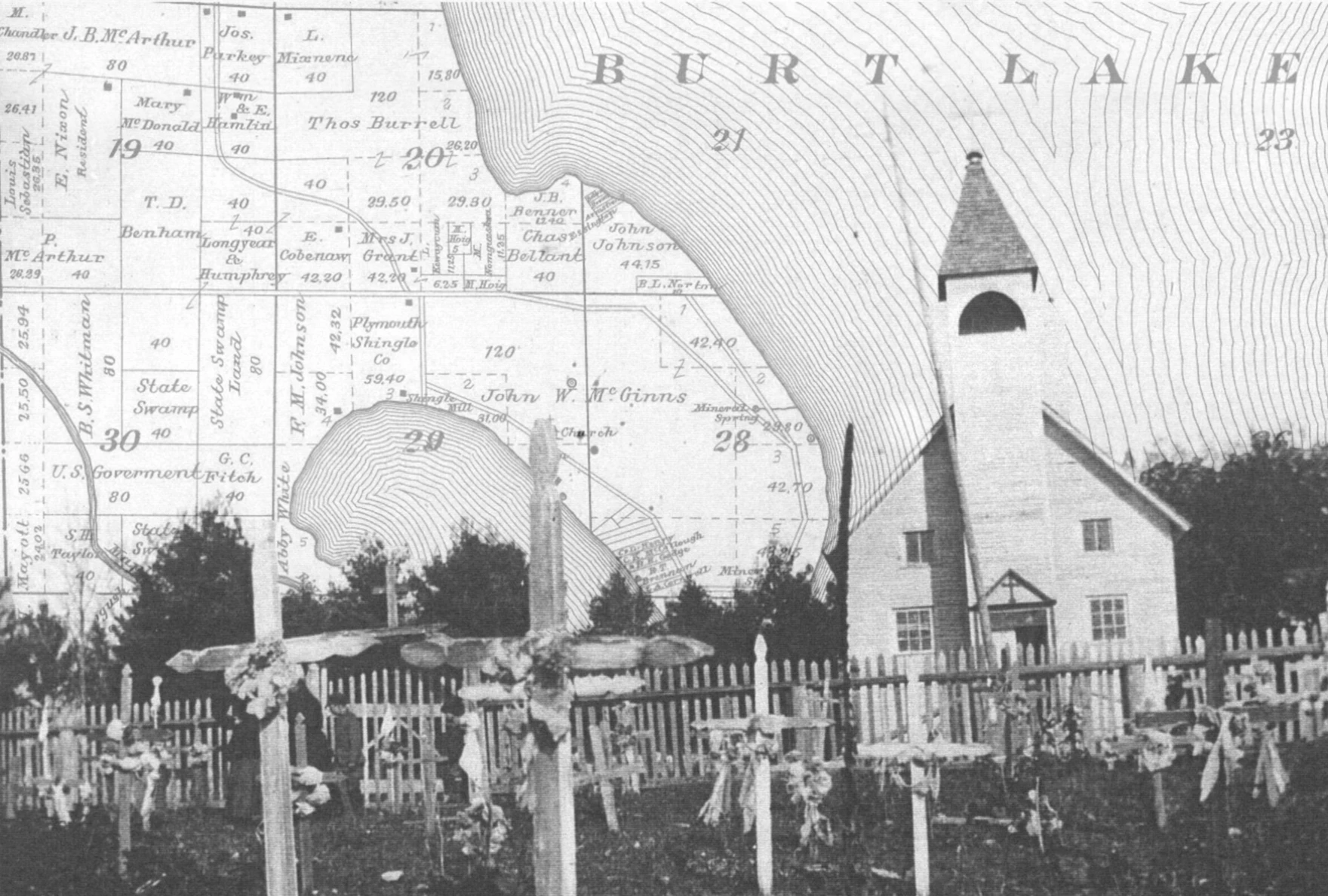

Road leading to Indian Village prior to the 1900 burnout. (credit: Burt Lake Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians)

LIVINGSTON: Word spread, letters were sent to legislators and some members of the Band were able to build new homes not far from Burt Lake. It took a decade, but the Band launched a legal fight in 1911.

Deborah Richmond is the Burt Lake Band tribal historian.

She says the villagers would have known their eviction was wrong, they just had to prove it in court.

DEBORAH RICHMOND: You know, it couldn’t have been that confusing at the time… There was a treaty, they were given land. They were– it was to be theirs forever. Why was it such a gray area?

LIVINGSTON: It took six more years for the case to even get on the judge’s docket.

Richard Wiles has researched the Band for almost five decades. He’s non-native but is an honorary member of the Band.

He says, even after the case was on the docket, there would have been a lot of turnover – judges, attorneys, tribal leadership – and it all made matters more confusing.

RICHARD WILES: After a couple of years of one person trying to deal with the case, they’d be gone, and a new person would come in, and they’d have to start over getting up to speed on what was going on.

LIVINGSTON: When it finally came time for the Burt Lake Band to present their argument, Richard says the members would’ve been excited and optimistic.

They had federal attorneys and documents to prove they owned the land in more ways than one.

Deborah Richmond again:

RICHMOND: We assumed like, absolutely, finally they’re gonna understand. Show the different things legally you need to show. So a judge will understand it and say, ‘Okay, this is ridiculous. And this is their property.’

LIVINGSTON: But John McGinn’s defense had an ace up their sleeve. Their strategy was to argue that the Burt Lake Band didn’t exist. It all comes back to the treaties.

The Band had actually signed onto two treaties. The 1836 Treaty of Washington and another one about 20 years later.

Matthew Fletcher is a professor of tribal law at University of Michigan and a member of the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa & Chippewa Indians.

He says the first treaty – The Treaty of Washington – created this fake tribe – the Ottawa and Chippewa nation.

In reality, there were all these individual bands – with their own unique identity and sovereignty. So, the second treaty was supposed to correct that.

It dissolved the fake Ottawa and Chippewa nation. But by dissolving it, it allowed some lawyers to argue that certain tribes no longer existed.

MATTHEW FLETCHER: And so, the problem with that for every tribe in Michigan has signed this treaty, most notably the Michigan Ottawas was that everybody looked at and said, ‘Oh, your tribe you agreed to terminate, self terminate, you’ve abandoned your tribal relations. You have no treaty rights, you’re out.’

LIVINGSTON: This is exactly what McGinn’s lawyers argued in court. In 1917, after years of waiting, it only took the judge 12 days to issue his verdict in favor of McGinn. He essentially ruled the Band wasn’t a tribe.

Deborah Richmond, the Band’s historian, calls it the first of many stinging losses.

DEBORAH RICHMOND: Justice was not served. And I’m sure they were just crushed. And again, that would just open the wound up all over again. All over again.

A 1902 Cheboygan County plat book showing John McGinn’s possession of the Burt Lake Peninsula that later came to be known as “Colonial Point.” (credit: Burt Lake Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians)

LIVINGSTON: Even though John McGinn died before the judge’s decision came down, the Burt Lake Band still could not return to their land – 17 years after the burnout. One of the only village buildings McGinn left standing was the Band’s Catholic church. In the years after the burnout, records show he used it as his pig barn.

McGinn sold off the individual parcels of land. Other people bought them and built their own homes. The peninsula was later renamed “Colonial Point” after a hotel that was built by the lake. After the judge’s ruling in favor of John McGinn, the Band’s identity in the eyes of the federal government was up in the air. Federal recognition is vital for a tribal community. It’s what unlocks money for healthcare, education, and the preservation of culture and history.

The judge’s ruling was not the end. The Band wasn’t going to stop there. The 1920s went by. It wasn’t until the Great Depression that the tribe saw a new way forward. In 1934, Congress passed the Indian Reorganization Act. It allowed tribes to petition to be officially recognized by the federal government – securing their own land and laws.

In Michigan at the time, four native tribes became sovereign nations with the passing of the IRA. But the Burt Lake Band was caught in what historian Richard Wiles calls a “catch-22.” Federal recognition was only granted to native communities that lived on their ancestral land.

RICHARD WILES: But guess what, the Burt Lake Band had lost their ancestor land, because it had been taken from them. And so the federal government said, ‘Well, you have no land. We can’t reaffirm you.’

LIVINGSTON: A petition to be recognized was signed and sent by all the Band’s membership at the time. Burt Lake, along with many other tribes throughout the country, never even got a response.

RICHMOND: Those are the things that just pile up generation after generation. Just makes you think, ‘You know what? Thought we were gonna get past this, but we are still, it seems, to be getting worse – as far as the ridiculous nature of how we are viewed and treated.’

LIVINGSTON: Decades passed and laws were amended. For a while, nothing legal happened with recognition, but the Burt Lake Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians wasn’t done pursuing it.

It was the summer of 1993. It had been nearly 100 years since the village was burned to the ground. And the Band decided to try for recognition again – this time through a bill in Congress. They sent a delegation to Washington, D.C.

Seal of the U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Indian Affairs.

On a warm September day, the Band Chairperson at the time, Carl Frazier walked through the U.S. capitol building on his way to address a House Subcommittee On Native American Affairs. He remembers it as a frightening experience.

CARL FRAIZER: I’m just… was an ordinary man and not not a lot of education. And uh… We had Congressman, we had senators and all the letters are in here.

LIVINGSTON: Carl is now 84. He sits at his kitchen table in Naubinway, the Anishinaabemowin word meaning “to gaze in wonderment.” It’s right on Lake Michigan.

Carl flips through documents in a binder as thick as a brick. He says it’s just some of the research material the tribe had to put together to pursue reaffirmation.

FRAIZER: Here’s my testimony here. The Burt Lake Band and it goes on there talking about the 1934 Congress… A lot of this stuff was done by the lawyers and I was kind of a tool to direct where we were going.

LIVINGSTON: The Band wasn’t petitioning alone. They were up for a congressional vote with three other Michigan tribes. More tribes, who were already recognized, sent in letters of support. And they had some U.S. Representatives in their corner. Their long wait for federal recognition seemed to be coming to an end.

In the subcommittee hearing room, Carl stood and delivered his address to a room full of members of Congress.

FRAIZER: ‘Chairman, members of the committee. My name is Carl Fraizer, and I am chairman of the Burt Lake Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians…’

LIVINGSTON: Carl reads that original testimony today from his home in Naubinway. In it, he says the federal government’s denial of reaffirmation to tribes, under the Indian Reorganization Act, was “erroneous and improper.”

FRAIZER: ‘These treaties, signature tribes, have the same status as any other Indian tribe, regardless of the Office of Indian Services’ financial inability to include them in and implement the IRA.’

LIVINGSTON: It’s one thing to claim all of that in a testimony – but the reaffirmation process is difficult even under the best of situations.

Matthew Fletcher, the professor of tribal law, says the process is burdensome, expensive and every detail about the tribe’s history, genetics, and cultural heritage needs to be correct and verified.

FLETCHER: A federal acknowledgement petition requires literal decades of research, you need to find every single document official quantity, that quality that actually says anything whatsoever about the tribe in play. You need to have written research about things that oftentimes cannot be written down about the culture. It is truly hideous, and a Kafka-esque process that I wish upon absolutely nobody in the world.

LIVINGSTON: Hideous though it may be, Carl left D.C. after his testimony with new vigor.

FRAIZER: I knew I was right. When you’re right, you can do things.

LIVINGSTON: But that was just one of many DC trips Carl ended up making. The three other tribes got their reaffirmation approved by Congress a year after the hearings – in 1994.

But for the Burt Lake Band, the petitioning process dragged on for another 13 years. Then, in 2006, the Department of the Interior came down with its decision. The Band’s reaffirmation request was denied. Another defeat. The decision said the Band didn’t meet all the department’s seven requirements for approval.

One of the issues raised was the Band’s cultural resemblance to the nearby Little Traverse Bay Band of Odawa Indians. After the federal government reaffirmed the Little Traverse Bay Band in the ‘90s, dozens of Burt Lake members joined the tribe. The Bureau of Indian Affairs essentially ruled the Burt Lake Band didn’t have enough people to make up a distinct community.

The other main issue was with its member lineage. Part of the reaffirmation process involves submitting a list of tribal members. The Band submitted multiple lists. And what the federal officials found was some of the people on the lists were either dead, belonged to a different tribe, or could not actually trace their lineage back to that original village.

On that list of people that actually didn’t belong to the Burt Lake Band was Carl Fraizer. Carl said it was a shocking discovery, especially since he had served as the Band’s leader for years.

CARL FRAIZER: There was a guy come in, he says, ‘You’re not even an Indian.’ And we had a people for in from Washington, DC lawyers and that. And I read he thought we weren’t part of the tribe. So, I just quit.

Picture taken on Burt Lake near Indian Village in 1900. From left: Joe Paki, Sam Kijigo, Mrs. Liza Nangeskwa, Mose Nangeskwa, John Nangeskwa. (credit: Burt Lake Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians)

LIVINGSTON: Carl is Native American. He can trace his lineage to at least one native ancestor. But a genealogist later told him that his lineage was more with the tribes in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. Carl is now an official member of the Sault Ste Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians. But after years of service to the Band, Carl still sees part of himself as Burt Lake. He gets emotional thinking about their story.

FRAZIER: I really felt bad about not getting– helping the tribe get recognized… but, you know, now I think about this all the time, what we did what we didn’t do.

LIVINGSTON: Carl wishes he could’ve done more to get the Band what it’s wanted for decades. But many of those who study tribal law believe the recognition process is rigged.

The Band’s lawyer Bart Stupak is trying to prove in court that reaffirmation stems from a white person’s knowledge of native culture. He’s a former U.S. Representative from Michigan.

BART STUPAK: Most Native Americans in Michigan identify with more than one tribe. BIA has found it very convenient to say, ‘Oh no, only one tribe.’ Tribes who are recognized through this acknowledgment process. They cannot meet the same acknowledgment process today. Because the interpretation of treaties… they have to be looked at in the eyes of the Native American people at the time.

LIVINGSTON: And do you feel like the BIA is doing that?

BART STUPAK: I think they’re trying to get there. But you have over 200, and what, 30 years have built in biases and prejudice against Native American people? BIA will say, ‘No, we’re the only ones who can give it, grant it. We through the goodness of our hearts will award you this. It’s nothing you have, it’s nothing you can expect, it’s nothing you’ve earned, It’s nothing you ever ever had from your birthright.’ Totally untrue. Sovereignty goes with the Native American. It’s not something that the federal government gives you.

LIVINGSTON: Not getting recognized in the 90s was a devastating blow to the Band’s efforts at sovereignty… Because under the law right now, they don’t get another shot. There’s a regulation that doesn’t allow tribes to petition for reaffirmation if they have already been denied.

Matthew Fletcher says that rule is completely arbitrary.

MATTHEW FLETCHER: It’s a bureaucratic nightmare to read the thing. It’s a morass of horrors is what you should call it

LIVINGSTON: There is work to get rid of the “one-try rule” so dozens of tribes all over the country can submit new petitions. A federal judge ordered the BIA to review the rule in 2023 because of the Burt Lake Band’s lawsuit.

We reached out to the Department of the Interior – who oversees the BIA – for comment on that. A spokesperson said they cannot comment on the rule while it’s under review. As far as the pitfalls of reaffirmation, the Department pointed to a recent effort in 2015 to make the process more timely and transparent.

“The Department continues to take concerns about the process seriously.”

The Burt Lake Band is not the only tribe that’s been denied recognition from the federal government. Since the 1980s, 53 tribes have petitioned for reaffirmation. Of those 53 only about a third of the tribes have been successful.

LIVINGSTON: What are the chances that BLB could get reaffirmation in the coming years? The reality of it?

FLETCHER: Probably close to zero. I mean, even if the Interior Department says that they’re going to acknowledge them, they’ll be sued for that decision. Somebody will sue them. Probably the state of Michigan or local units of government, maybe even one of the tribes. I don’t know… we’ll leave it at that – very little chance.

Flag of the Burt Lake Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians.

(sounds of meeting)

LIVINGSTON: Now it’s April 2024. It’s been more than 120 years since the burnout, and the Burt Lake Band gathers for its monthly tribal council meeting. Since many of the members are scattered around the state, they meet this month in a town called Okemas – which means “Little Chief.” It’s nearly three hours south of Burt Lake.

But the Band does own some land near the old village – a few acres with an office building, a Catholic church and a small nature preserve. They hope to build a cultural center there in the coming years. But even after a century of frustrating battles, this is a merry gathering.

BRUCE HAMLIN: Do we have a prayer-giver today? Thanks be to the Great Spirit for all the good. Amen. Alright.

LIVINGSTON: Bruce Hamlin is running the meeting; he’s served as Tribal Chairman for more than a decade. Even though federal recognition may be tough – maybe impossible, Bruce says it’s still worth pursuing for the benefits, the funding and the justice.

HAMLIN: As a council, our main job is to establish reaffirmation. That’s what keeps the fighting spirit. So, it’s always there. And that’s kind of part of what makes you Burt Lake is that you’re working towards that.

DON PARKEY: “The biggest part of that process right now is waiting. And if anybody tells a Burt Laker they don’t know how to wait. They are wrong. We know how to wait.”

LIVINGSTON: That was tribal elder Don Parkey. Aside from recognition, he and his wife Nola say they’re focused on passing knowledge to the next generation.

NOLA PARKEY: We’re losing our elders. We’re losing the group that was there that experienced that. And our fear was that if we went much longer, all of those people that have that knowledge – they’re going to be gone.

LIVINGSTON: Nola hopes new people rediscover their Native American heritage. That’s what happened to Deborah Richmond. She only recently became involved with the Band and now she’s the historian. She says she’s passing the Band’s culture to her children. And she’s careful not to leave out details of the burnout and the push for recognition that came afterwards.

RICHMOND: “They will understand– they will understand how important this has been to us, and they will carry it on. For us and for themselves someday.”

The historic St. Mary’s Cemetery is located off of Chickagami Trail in Brutus, not far from where the Burt Lake Band’s village stood before the 1900 burnout. (credit: Michael Livingston / Points North)

(sounds of birds chirping)

LIVINGSTON: Ken Parkey is walking where the Burt Lake Band’s village once stood. He’s a tribal elder that lives nearby.

He’s in a cemetery filled with a few dozen white crosses. It’s on top of a hill overlooking the lake… surrounded by a chain linked-fence and expensive lakefront homes. Ken scans the land, looking for signs of the old village.

KEN PARKEY: I was always told it was down in that area. Right down in there. Yeah, about where that little valley is, kinda back over that way. That’s where I was told where it was at.

LIVINGSTON: This cemetery is one of the only signs left of that original village. It used to be attached to the Catholic church. The names of ancestors are written on a plaque near the entrance. Names like Elizabeth Hamlin, Steve Tawa and Susan Gijigowe. Some of Ken’s ancestors are buried here.

KEN PARKEY: I don’t know if this grave right here was my Great, Great Grandfather or not.

LIVINGSTON: Even though it looks a lot different from how it did in 1900, this is still a beautiful place – a place that will always mean something to the Burt Lake Band.

Members of the Burt Lake Band participate in the 2015 Walk of Remembrance. The group does the trek every fall from the site of the old Indian Village heading north about three miles. (credit: Burt Lake Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians)

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Points North: More Than Just a Filet of Fish

Points North: The Quest for Kiyi

Featured image: Photos courtesy of the Burt Lake Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians. (Photo illustration: Michael Livingston / Points North)