“Nibi Chronicles,” a monthly Great Lakes Now feature, is written by Staci Lola Drouillard. A Grand Portage Ojibwe direct descendant, she lives in Grand Marais on Minnesota’s North Shore of Lake Superior. Her nonfiction books “Walking the Old Road: A People’s History of Chippewa City and the Grand Marais Anishinaabe” and “Seven Aunts” were published 2019 and 2022, and the children’s story “A Family Tree” in 2024. “Nibi” is a word for water in Ojibwemowin, and these features explore the intersection of Indigenous history and culture in the modern-day Great Lakes region.

It was a Minneapolis cousin who first introduced me to ticks. Summer visitors, the plan was to take our urban relatives fishing and swimming in the Minnesota woods. The morning of the excursion, my cousin emerged from the house wearing thick, yellow knee socks over her jeans and a plastic raincoat that covered her from head to toe. I stared at her, trying to figure out why she would subject herself to such torture.

“Ticks!” she said, “they bite you and burrow under your skin!”

Even though we spent our summers playing around in the woods, I had never seen a tick, let alone had one burrow under my skin. It turns out that burrowing is one of the many misconceptions about ezigaawag — wood ticks. My friend Krishna Woerheide is the resident expert. She is the Environmental Director for the Grand Portage Band of Ojibwe and has recently been asking the people in Cook County to give her their ticks as part of ongoing research related to the local moose population.

As Woerheide explains: “this was born out of a project regarding the North American Moose [mooz, Alces alces] which is a culturally important subsistence species for the Anishinaabe, and are declining due to calf predation, pathogen transmission, and winter tick loads, all of which have been amplified by climate change.”

Woerheide’s work involves tick collection, categorization, and testing. She says that “all the ticks we receive are identified, stored in alcohol, and sent to the various CDC facilities; deer ticks are sent to the Bacterial Diseases Branch in Colorado, and wood ticks are sent to the Rickettsial Zoonoses Branch in Georgia. If I start finding lonestar ticks in the submissions, I’ll send those to Colorado as well.”

The hunt for tick varieties began when she discovered that 30-40% of the local moose had “serological signs of having had Lyme Disease at some point.” Lyme Disease is carried by deer ticks, a species that is relatively new to Cook County. Woerheide wanted to know where moose were picking up the deer ticks and decided to start by asking the Sawtooth Mountain Clinic to collaborate, asking people to bring in the ticks that they find on themselves or their pets.

The goal was to locate “hotspots,” and narrow down general locations where a “tick drag would be fruitful.” The project is in the interest of public health — both human and moose. Having citizen scientists submit ticks from all over the county gives Woerheide the opportunity to see when/if invasive tick species show up here, “like the asian longhorned tick, or if the leading edge of other species of medical importance are starting to encroach, like the lonestar.” Collected samples show that neither of those have made it to Cook County, but both would bring consequences for humans and animals as carriers of disease-causing bacteria.

I asked Woerheide about my theory that wood ticks were not here until recently, and she said, “a lot of people over the years have told me that they grew up here and there used to be no ticks of any sort. In fact, when I started this project, a pretty common belief was that there were no deer ticks in Cook County at all.”

Based on four years of research, Woerheide can confirm that deer ticks are here. Sometimes mistaken for baby wood ticks, deer ticks are a whole different species. These ticks are tiny but carry a big impact, because 26% of them now carry Lyme Disease. The transmission of Lyme to a “host,” is the stuff of nightmares.

Questing male Wood Tick (Dermacentor variabilis). (Photo courtesy of Krishna Woerheide)

Here is how the biology works: Ticks are types of mites that have 3 stomachs — a foregut, a midgut, and a hindgut. Ticks molt between each of their life stages and lose their outer layer of skin everywhere except their midgut. This is where the Lyme bacteria wait for the bite. When the tick finds a suitable host, it creates an adhesive to anchor its mouthparts and seal the lesion during feeding.

“This is why they’re so difficult to remove,” says Woerheide, adding that: “tick mouths have tiny sawblade-like parts called chelicera which they insert and retract repeatedly to make a hole in your skin, similar to the motion of a kitten kneading your lap — but way less cute.”

The barbed mouth is a little bit like a harpoon, and enters the host like a straw. This “sawing and harpooning” is why it takes 24 hours to transmit Lyme Disease. Lyme bacteria are transmitted from the tick’s salivary gland and are awakened in the midgut when touched by the host’s blood meal. The bacteria then migrate out of the midgut into the haemolymph (tick blood), and find their way into the salivary gland.

Woerheide’s work confirms that deer ticks acquire most of the pathogens they vector from small mammals — primarily white-footed mice. And based on four years of tick-tracking results, she has learned that most of the deer ticks here in Cook County have come from the Highway 61 corridor, or close to it, with “none of the deer tick submissions thus far, coming from interior forests.”

Milt Powell-iban, was raised in the backwoods along the border country. He told me the story of how he and his brother encountered a moose on their trapline one winter that was covered in a blanket of ticks. The moose was clearly debilitated, and Milt and his brother spent some time picking off as many garments as they could “make an honest moose out of him.”

This story from the 1950’s indicates that winter ticks have been attaching themselves to moose for a long time. Woerheide clearly explains the difference between winter ticks and wood ticks like this: “A wood tick (Dermacentor variabilis), AKA American dog tick, is a three-host species, which means it must have a blood meal from a separate host for every life stage. The newly hatched larvae will find some small mammal, feed, drop off into the leaf litter, molt into a nymph, and then quest to find another host. After feeding on the second host, the nymph drops off, molts into an adult, and then quests for one, final time.

She confirms that, “for the wood tick, all of this happens in the summer months, and they are dormant or semi-dormant throughout the winter.” In other words, ticks won’t come after you through the snow.

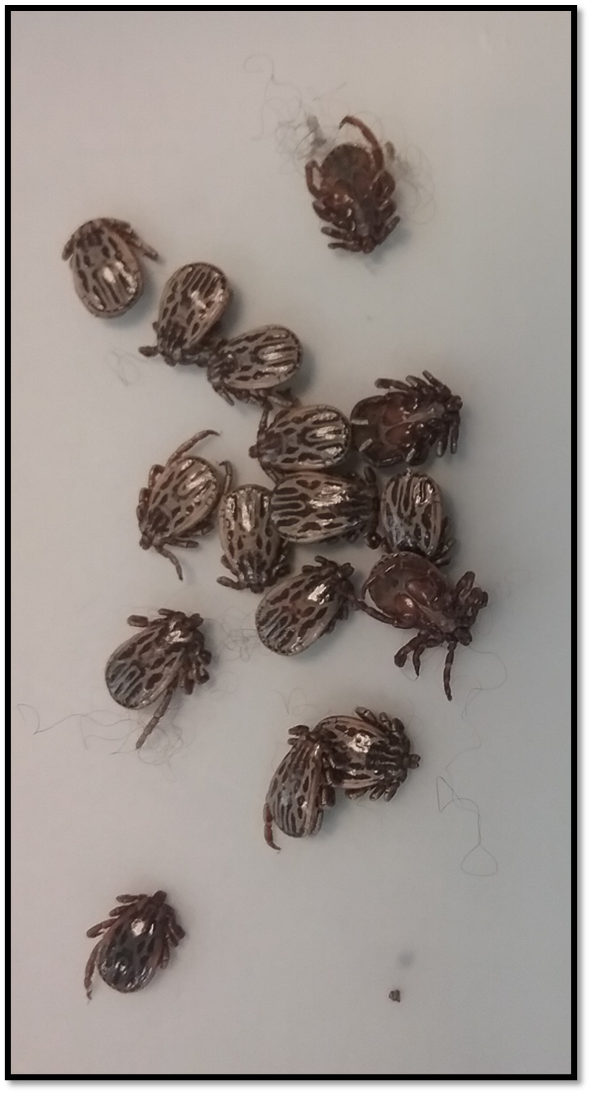

Male winter tick ornamentation. (Photo courtesy of Krishna Woerheide)

A winter tick (Dermacentor albipictus) is a single-host tick that quests large ungulates like moose. “This means they get on one animal and stay there through all life stages until fat with a blood meal in the spring, and then will drop off into the leaf litter or the snow, depending on the type of spring we have. Winter ticks enter their larval stage in the fall, which is backwards from most other species of tick, and stay on the animal throughout the winter. They are sometimes called ‘moose ticks’ because they cause a lot of problems for moose.”

As Milt discovered, and as Woerheide notes, “infestations can be in the tens of thousands, and cause hair loss (from constant itching), anemia, protein deficiency, and disruption in the animal’s thermoregulation abilities.”

Woerheide’s winter tick studies are based on the Grand Portage Reservation (Gichi Onigaming), Isle Royale National Park (Minong), and within the 1854 Ceded Territory (greater northeastern Minnesota) — all of which are the ancestral and present homelands of the Grand Portage people. This is why the Band has a vested interest in the health of Tribal resources on and off the Reservation, and disease vectors are one of many components of that.

So, what is the future of tick populations in your neighborhood? Woerheide says that ticks are extremely resilient. Deer ticks can survive extended temps of -7 degrees, and she has had petri dishes of winter tick larvae survive “for months” in the refrigerator.

“As long as they have access to their preferred over-winter habitat — plenty of leaf litter and/or ample insulative snow cover,” ticks of all varieties can over-winter. In fact, “the adult ticks we are seeing emerge in the spring, are the ones who didn’t find a meal in the fall and have waited it out through the winter.”

One of the consequences of warmer winters, could be that wood ticks and deer ticks begin to stay active all year. As Woerheide says, “33-40 degrees Fahrenheit seems to be the magic temperature range. Any time the temperature gets above that, they’ll be out questing.”

The official 2023 results should be available this summer, and Woerheide’s work continues until it is time to send specimens to the CDC in the fall.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Nibi Chronicles: The Return of Nenookaasiwag

Nibi Chronicles: The nation-to-nation fight against extractivism

Featured image: Fat engorged female winter ticks (Dermacentor albipictus) in a moose bedsite. (Photo courtesy of Krishna Woerheide)