By Daniel Wanschura, Interlochen Public Radio

Points North is a biweekly podcast about the land, water and inhabitants of the Great Lakes.

This episode was shared here with permission from Interlochen Public Radio.

Dave Naftzger found out about the 100% Fish Project entirely by accident. He was headed to Europe on a business trip, but first had a long layover in Iceland. So, he did some research to see what he could do while he was there.

That’s when he came across a project where people had figured out how to use and sell almost 100% of every fish they caught, specifically Atlantic cod, Iceland’s most iconic fish. Dave is the executive director of the Conference of Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Governors and Premiers, an intergovernmental organization, and this caught his attention. He set up a meeting with the main guy, Thor Sigfusson.

“Walked into his office, he had a fish skin, fish leather lamp,” said Dave. “And he had a table with all these different products that would be made from parts of the Icelandic cod that used to be put in landfill. It really was inspirational.”

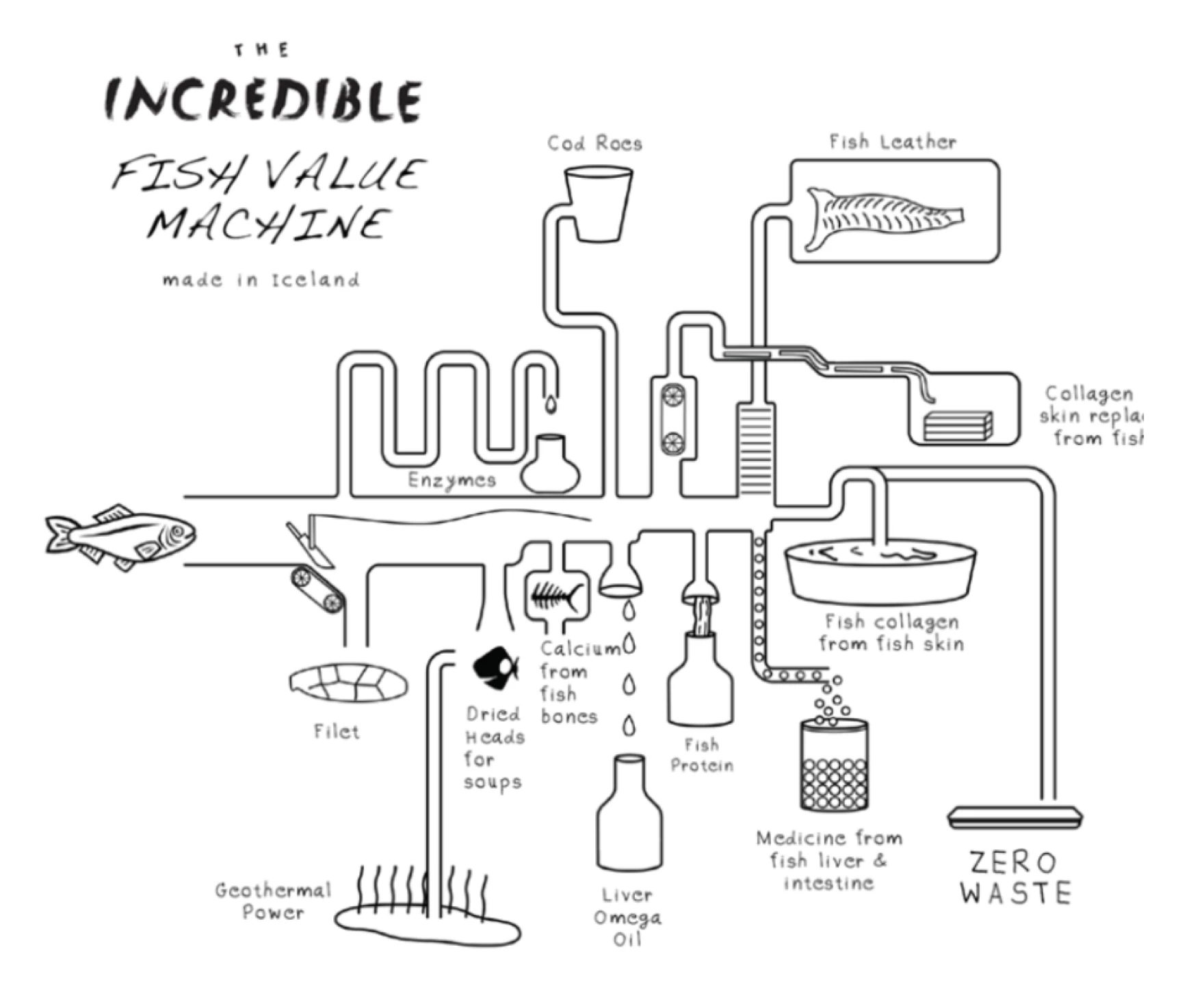

Thor started the Iceland Ocean Cluster in 2011. It’s an innovation hub that brings people together from different industries. Their goal: to figure out how to use 100% of every fish caught. Traditionally, the cod filets were sold and then the remaining 50% or so would either be thrown away or used for low-value products like animal feed. Thor saw an opportunity for the fishing industry to make more money from those parts of the fish. And it’s been a huge success. Now, his innovation hub helps create new and existing products – things like beauty products, skin graft bandages and durable leather. These markets increased the value of Atlantic cod from about $15 to over $5,000.

After hearing all about it, Dave started wondering if something like the 100% Fish Project could help the struggling Great Lakes fishery. He took the idea home to find out.

Credits:

Host / Producer: Dan Wanschura

Editor: Morgan Springer

Additional Editing: Peter Payette, Ellie Katz, Michael Livingston

Music: Trod Along, La Naranja Borriana, Shelftop Speech, Tall Harvey, Temperance, Thimble Rider Theme, by Blue Dot Sessions

Carlson’s Fishery opened in 1904 at Fishtown in Leland, Michigan. (credit: Dan Wanschura / Points North)

Transcript:

DAN WANSCHURA, BYLINE: This is Points North. A podcast about the land, water, and inhabitants of the Great Lakes. I’m Dan Wanschura.

(sounds of Carlson’s Fishery)

JIM VERSNYDER: Here’s how you filet one if you want to learn how. They’re big fish, and they’re kind of hard to cut because I’m out of shape, to tell you the truth.

WANSCHURA: Jim VerSnyder is sitting at a big stainless steel table. It’s covered in fish blood. He’s got a long, sharp knife in one hand, and with the other, he reaches into a bin filled with ice, pulls out a fish, and plops it on a cutting board.

VERSNYDER: You gotta really push hard. You gotta keep right down on this backbone. Otherwise, your knife will squirt out the side. These are really firm rock hard fish. So, they’re hard to cut. But when you get done, they are gorgeous.

WANSCHURA: Jim is 76 – a big guy in bright yellow, waterproof bibs, and a blue bandana tied around his head.

VERSYNDER: Well, you should have seen me when I was 30. I was a machine. Hahaha. … These guys got me down here fileting when I should be retired.

Jim VerSnyder (right), Mirk Burda (center), and Nels Carlson (right) filet whitefish at Carlson’s Fishery in April, 2024. (credit: Dan Wanschura / Points North)

WANSCHURA: Jim is part of a small assembly line of workers at Carlson’s Fishery. It’s in this historic spot called Fishtown in Leland, Michigan. Right on Lake Michigan. A bunch of these fishing shanties. Carlson’s is a shop that sells directly to customers. And today, a local fisherman just brought in the first catch of the year. About 1,700 pounds of fresh whitefish.

VERSNYDER: They are gorgeous. You’re not going to find anything much better looking than this. It was swimming this morning.

WANSCHURA: Jim finishes fileting the whitefish and tosses it on a pile in the middle of the table. Then, he slides the rest of the carcass – about half of the fish – into a big rubber garbage bin. Just a few years ago, Carlson’s Fishery was dumping all of those fish scraps in a landfill.

Thousands and thousands of pounds of fish biomass. Basically, if it wasn’t a filet – it was thrown away. But that’s a whole lot of wasted potential, especially at a time when the Great Lakes commercial fishing industry has been declining for years.

Right now, the value of an average Great Lakes whitefish is around $15. But there’s a project that’s trying to double – even triple that amount in the next several years. And it does that by finding ways to use parts of the fish that are often thrown away. This project is based on a success story in Iceland, and that’s where we begin, right after this.

(sponsor message)

WANSCHURA: Erla Pétursdóttir grew up in the small fishing town of Grindavík, Iceland. Her grandfather started a fishing business there in 1965, and it was a tough way to make a living.

ERLA PÉTURSDÓTTIR: He was just trying very hard for his family to thrive. And that was quite a struggle for him and … no one was really making a lot of money. So, and it was always trying to fish more and more.

WANSCHURA: In other words, too many boats fishing too few fish. In 2000, Erla’s father took over the business, and it was all hands on deck.

PÉTURSDÓTTIR: I just remember working in the fishing industry – started in the summers when I was 12, and was working and that was just what people did.

WANSCHURA: She says some kids even took off school or worked night shifts when the fishing season got really busy. But Erla just couldn’t imagine a future in the family fishing business.

PÉTURSDÓTTIR: People used to say, ‘Oh, you need to go to school. Otherwise you’ll just end up in the fishing industry.’ Like, cause it was only unskilled positions, or no chance of moving up.

WANSCHURA: So, when she was 16, she moved away from her family to go to school in Iceland’s capital, Reykjavik. From there she went to Minnesota for college.

PÉTURSDÓTTIR: I did a double major: computer science and economics, with my math minor. Did a lot of everything.

WANSCHURA: After graduating, Erla got a job at an energy consulting firm in downtown Minneapolis. Working in Iceland’s fishing industry was the farthest thing from her mind.

One of the fish Erla’s family relied on was Atlantic Cod.

Atlantic cod has is the most iconic fish species in Iceland. (credit: Government of Iceland)

PÉTURSDÓTTIR: We didn’t grow up eating cod … we ate haddock. … Because cod is so valuable. (laughter).

WANSCHURA: It’s Iceland’s most iconic fish and has been the lifeblood of the island’s economy for a long time. But due to overfishing, the cod population began to plummet. By the 1980’s, the Icelandic government put in fishing quotas – strict regulations that limited the number of fish caught. And that meant Iceland’s commercial fishery started looking for more ways to increase the value of their catch.

The filet of a typical cod is around 40-50% of the entire fish, and for many in the industry, not much thought was given to that other part of the fish.

THOR SIGFUSSON: Fifty percent were thrown away.

WANSCHURA: Thor Sigfusson was born and raised in Iceland. He says the commercial fishery zeroed in on a few things that were going to waste:

SIGFUSSON: The fish skin and the bones and the liver and the bladder, et cetera. Those parts of the fish that had not been utilized previously.

WANSCHURA: First, they went to products like animal feed. Not necessarily a ton of value there, but still, better than throwing it away.

When Thor was working on his PhD at the University of Iceland, he decided he wanted to build on that innovation. And he had this crazy idea: to find ways to use 100% of each fish caught.

SIGFUSSON: So, I thought to myself, we need to establish some kind of community that connects … fishermen with the scientists, with the startup world, and with other parties that can help.

The Iceland Ocean Cluster’ goal is to figure out how to use 100% of every fish caught. (credit: Iceland Ocean Cluster)

WANSCHURA: Thor says at first, some people were skeptical about his idea. Why focus on the fishing industry? It’s not exactly a cutting-edge field.

SIGFUSSON: And they were all thinking like … this is a part of our past. This is part of our history. We’re proud of that history, but I’m not going to become a fisherman or a fish processor.

WANSCHURA: So, Thor creates the Iceland Ocean Cluster, this innovation hub that brings people from different industries together. And their main goal is to figure out how to use 100% of each fish and make more money doing it.

Pretty quickly all these ideas started popping up. Like how fish enzymes in the cod’s guts could be used for skin and beauty products. Nutraceutical proteins could be gathered from fish heads. Highly specialized skin graft bandages could be made from fish skin. Fish skin could also be used to make gelatin and collagen, and one of the most durable types of leather.

SIGFUSSON: And I always remember when a guy came to me some four years ago, he was dressed in this black leather suit. And he said to me, “I want to be a part of the Ocean Cluster.”

And I said, “What do you do?” He said, “I’m a clothing designer”. And I said, “I love the designing part, but I guess not– clothing is probably not my cup of tea.” And he says, “You see, I’m wearing my design. This is actually salmon leather that I’m designing clothes from.”

WANSCHURA: Salmon leather.

SIGFUSSON: And I said, right away, “You’re in.”

Samples of lake trout leather. (credit: Great Lakes St. Lawrence Governors & Premiers)

WANSCHURA: This part gets a little complicated. So stay with me. There’s the dock value of a fish, and then there’s the amount of money you get from all the products that come from that one fish. That’s what we’re gonna be talking about here. Thor says, in the past, a 10 pound cod typically generated about 15 dollars – that was just for the filet. But now, with all these new markets, that same fish can generate over 5,000 dollars.

Again, not that each fish is now worth five grand, but all the products that come from each fish. A lot of that increase comes from those valuable skin graft bandages which are really expensive.

Now, you might be wondering what the fishermen get from all this. Thor says it’s hard to pinpoint exactly how much more they’re getting per fish, but he says it’s increased considerably too.

In case it’s not obvious, Thor says the 100% Fish Project has been a huge success.

SIGFUSSON: Young people are not that excited about being fishermen, but they may be really excited to do some marketing of these products.

WANSCHURA: And that success is attracting people like Erla Pétursdóttir. After working in Minneapolis, Erla felt the call to return home to Iceland, and to her family’s fishing business.

PÉTURSDÓTTIR: So, you need the engineers and the software designers, and you need the marketing people, and you need the biotechnicians, and anything you know, quality control. … So, there’s just– there’s so much going on in industry that that’s what called me back.

WANSCHURA: Today, Erla heads up Marine Collagen – a joint business made up of her father’s fishing business and a few others. They make collagen and gelatin from fish skin.

PÉTURSDÓTTIR: So, the trend in Iceland has sort of always been to use as much as we can, to using everything, to not just using everything to getting the highest value out of everything.

WANSCHURA: A guy from the Great Lakes learned all about this by accident. His name is Dave Naftzger. And he’s the executive director of a group that’s a total mouthful. It’s called the Conference of Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Governors and Premiers – basically, a Great Lakes intergovernmental organization. About five years ago, Dave had a long layover in Iceland, and decided to make the most of it.

DAVE NAFTZGER: So, I did some research about different things that were going on in and around Reykjavik, the capital. And learned about the Iceland Ocean Cluster.

WANSCHURA: Thor Sigfusson’s innovation hub that was trying to use 100% of the fish. Dave saw a ton of parallels between what happened to cod in Iceland in the 80s and what was happening in the Great Lakes fishery with whitefish today. So, he set up a meeting with Thor.

NAFTZGER: Walked into his office, he had a fish skin, fish leather, lamp that was a piece of art hanging. And he had a table with all these different products that were being made from parts of the Icelandic cod that used to be put in landfill. So, it really was inspirational.

WANSCHURA: Dave took that inspiration, brought it back to the Great Lakes, started the Great Lakes 100% Fish Pledge, and came up with an action plan.His team began by sending whitefish to Iceland for biotechnical testing. Basically to see what other products whitefish might be used for. And some of the findings were a lot like cod.

The 100% Great Lakes Fish Pledge hopes to get the fishing industry using all parts of a fish by 2025, ideally in value-driven ways. (credit: Great Lakes St. Lawrence Governors & Premiers)

NAFTZGER: They identified things like fish leather from the skin. Collagen that could be made from the skin and from the scales, fish meal and oil that can be made from the viscera or the guts and a couple of other products as well.

WANSCHURA: Which brings us back to those complicated numbers – the amount the fisherman gets at the dock for a fish versus all the money that comes from products made from each fish. Right now, for Great Lakes whitefish, the product value is between 10-15 bucks. And that’s coming entirely from the filet. That’s what’s being sold.

And while it might not be realistic to expect the same increase as cod, Dave says he hopes the project doubles, even triples the value generated from a Great Lakes whitefish in the near future. And that’s no small thing.

Dave says they’ve done similar testing with other Great Lakes fish, like walleye, lake trout, yellow perch and white sucker. They’ve got big goals for them too.

(sounds of Carlson’s Fishery)

Back in Carlson’s Fishery in Leland, Michigan, co-owner Mike Burda is at the end of the fish filet assembly line. He’s spraying the fresh filets down with water, to get any blood off.

Carlson’s hasn’t been bringing fish scraps to the landfill for a couple years now. Instead, they bring it to the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians for composting. It’s putting the rest of the fish to good use, but a use Carlson’s isn’t currently getting any money from. Mike hopes the 100% Great Lakes Fish Pledge changes that.

Mike Burda, co-owner of Carlson’s Fishery, sprays the blood off of a freshly-fileted whitefish. (credit: Dan Wanschura / Points North)

MIKE BURDA: I hope that it allows us to be able to be successful with a little less work than we’re currently doing. And then, obviously, to make use of all of this natural resource is a big thing. And then I hope it’s lucrative. I hope it brings in new revenue that allows you to make money a little bit easier, you know?

WANSCHURA: And they might catch an initial break on that. The Grand Traverse Band is talking about developing a liquid fertilizer with the fish parts. They could sell it, and Carlson’s would be a part of that revenue stream.

So far, about 25 businesses in the Great Lakes have signed on to the 100% Fish Pledge. The goal for these businesses is to find ways to use 100% of the fish by 2025 – next year.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Points North: The Quest for Kiyi

Points North: Not always the apex predator

Featured image: A bin of freshly-caught whitefish at Carlson’s Fishery in Leland, Michigan. (credit: Dan Wanschura / Points North)