An eerie sight is blossoming throughout coastal wetlands in Georgian Bay: ghostly grey specters lining the shores behind otherwise healthy-looking wetlands.

“Do you see these dead trees?” asked Patricia Chow-Fraser. The McMaster University biologist was addressing attendees of a lecture at The Water Institute at the University of Waterloo in early March.

Of course, we saw them — they were impossible to miss. But the lecture had only begun, and no one was brave enough to raise their hand.

“You are very shy. Well, I don’t know any other biological term to describe them, or ecological term. They’re just…dead trees,” said Chow-Fraser.

And these clusters of dead trees hugging the shore are a recent phenomenon, Chow-Fraser added: “The cottagers that I talked with, they’ve never seen them for the last 50 or 60 years.”

The culprit is water levels — specifically extreme fluctuations in water levels in Georgian Bay, a little sibling to the Great Lakes located entirely within Ontario. Hydrologically, Georgian Bay is connected to Lake Huron and is not subject to the same rigorous water level regulation seen in Lakes Superior or Ontario.

Ultimately, water levels in a body of water as large as the Georgian Bay will naturally change. As water moves inward on a shoreline, and those water levels rise or expand to cover root systems, trees naturally die off. For Chow-Fraser, what’s unprecedented is how extreme such water level instabilities are.

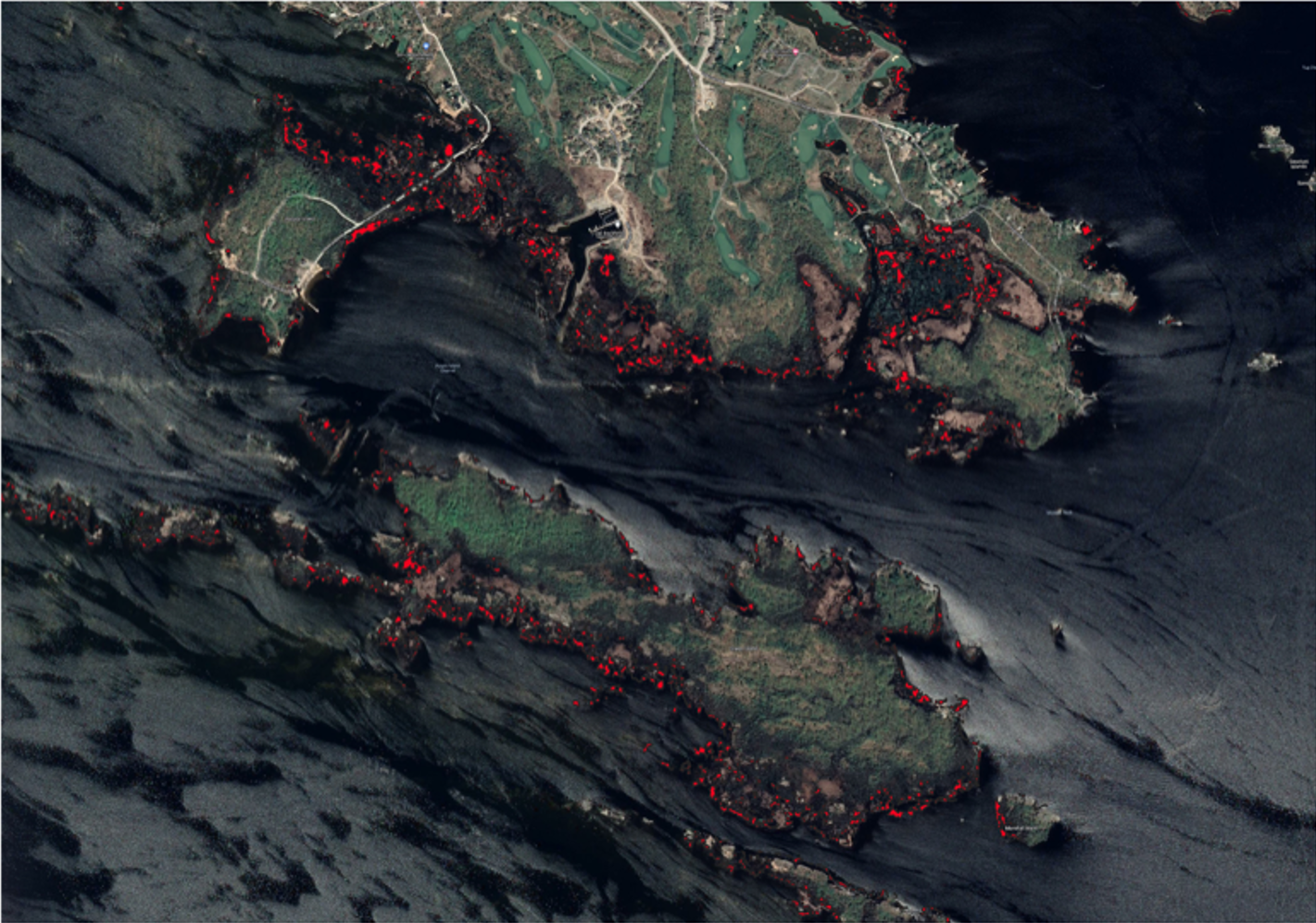

Green Island and Potato Island in 2019. The red signifies dead trees. (Photo courtesy of Dr. Patricia Chow-Fraser)

Water level fluctuations were relatively stable throughout the 20th Century. Yet beginning in 1999, water levels dropped below the average level going back one hundred years. Water levels stayed atypically low for the next 16 years before rising almost three feet, significantly above the century-long mean. And they stayed there, year after year.

Chow-Fraser believes that aquatic plants migrated further into the bay when water levels dropped, leaving shrubs and trees to expand into areas once covered in water. Since the water stayed low for so many consecutive years, the trees — mostly pine — put down significant root systems and grew sturdy and tall. When the water eventually returned, the trees took five years before succumbing to the inundation.

“It’s only when you get this combination of really prolonged low water followed by a really rapid increase that you get this sort of pattern,” Chow-Fraser told the group. “But the question is: Does this dead tree zone… vary across wetlands? And how does aquatic vegetation change across these various periods, as well as the fish community?”

Across the Zooniverse

Change of Tadenac Wetlands. (Photo courtesy of Dr. Patricia Chow-Fraser)

Chow-Fraser’s report, published in the February 2024 edition of the journal Landscape Ecology, clarified that studying how these dead tree zones impacted the ecology of nearby wetlands was beyond the scope of their initial research project. However, she noted that the dead tree zones were created at the expense of plants often used by wetland fish and birds as nurseries, as well as amphibians and reptiles.

It isn’t a stretch to think that massive changes in the make-up of wetland ecology in the coastal areas of Georgian Bay would have some impact on local wildlife, she reckoned. However, determining what those interactions would be up to future studies.

So, Chow-Fraser and her team organized those future studies. Finding money to conduct lengthy environmental research is a challenge, let alone in locations far from where universities and governments are headquartered. Yet, in pivoting to explore how dead tree zones affected wetland wildlife, Chow-Fraser partnered with cottagers and deep-pocketed anglers curious to know if extreme fluctuations in water levels were harming critical fish and waterfowl habitat. (In 2022, for example, groups like the Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters and Ducks Unlimited were among those awarded $6.7 million CAD [$4.9 million US] towards enhancing wetlands throughout the Great Lakes basin.)

Change of Tadenac Wetlands. (Photo courtesy of Dr. Patricia Chow-Fraser)

“Fish are something that a lot of people identify with,” Chow-Fraser told lecture attendees. “I turned ‘wetlands’ into ‘fish habitat’ and I got funding and never looked back. It was just miserable trying to get wetland work funded.”

However, studying fish communities near dead tree zones provided its own challenges. Similar to mangroves, the dead and dying pine trees had dense root structures that didn’t allow for larger fish to pass through easily; the presence of so much organic matter could also lead to algae build-ups in small bays with narrow openings that the shifting currents of Georgian Bay couldn’t easily flush out.

Meanwhile, higher water levels also meant Chow-Fraser and her team couldn’t easily sample the same sites (critical for scientific research) using traditional netting techniques because the new waterline was higher than the frame of their nets. They worried that the fish would quickly escape.

While Chow-Fraser proposed the workaround of using cameras to film whatever fish species still used modified wetlands near dead tree zones, making it happen fell to her doctoral student, Danielle Montocchio.

With the help of her father (himself an avid fisherman) to reverse engineer the problem, Montocchio began troubleshooting ways of capturing high-definition footage of significant hours of wetland activity. When looking into existing options, Montocchio found that most were geared towards marine research expeditions, technology that could be submerged dozens of feet and withstand significant underwater pressure.

“They were overkill for our needs,” Montocchio told Great Lakes Now.

Montocchio recognized that simplicity is always better when stretching thin research budgets to the max. So, she acquired eight off-brand GoPros with waterproof casings and mounted them to PVC piping secured to a five-gallon bucket filled with cement.

“To make up for the fact that an action camera has a very narrow field of vision, we dropped a bunch of them all over the place to try and capture as much fish as we could,” she said. “It was definitely not an elegant solution, but it worked.”

Change of Franklin Island Wetlands. (Photo courtesy of Dr. Patricia Chow-Fraser)

Having solved the problem of how to monitor fish populations, Montocchio faced an even more daunting task — how to sort through 140 hours of footage of wetland plants (and, she hoped, fish) gently swaying with the current.

“I decided to use people power,” said Montocchio.

She applied to have her fish research project dubbed ‘Where’s Walleye?’ featured on Zooniverse, a global platform linking researchers with volunteers of all ages from around the world looking to help sort through reams of data. And sort they did.

Now, Montocchio is focusing on analyzing differences in fish size, species, and presence in areas in and around the dead trees. As part of her doctoral research, she hopes to understand their impact on fish populations better. She has also started a working relationship with machine learning researchers at Stanford University in California to see if she can use her data to train artificial intelligence better to identify specific species and cut down on false positives.

“This is an issue that a lot of freshwater researchers are encountering,” Montocchio said.

Water levels and water quality

Change of Franklin Island Wetlands. (Photo courtesy of Dr. Patricia Chow-Fraser)

Water levels in Georgian Bay, and indeed among all the Great Lakes, are expected to rise and increase in variability in the coming decades. Environment Canada released a 2022 study suggesting Lake Michigan-Huron could see as much as 13 feet in water level variation.

Tied to the issue of water levels is the issue of water quality, something Mary Muter, Chair of the Georgian Bay Great Lakes Foundation, has worked tirelessly to promote. Her organization has worked closely with Chow-Fraser (including hosting her team and supporting their research financially) along with nearly every governing body on both sides of the Canada-US border to sound the alarm over what she told Great Lakes Now is the “unfair management of water levels in the Great Lakes.”

In 2021, Muter’s colleagues sampled 70 sites along the Georgian Bay Township coastline for E. Coli and found numerous instances where the E. Coli concentration in the sample was dangerously above Health Canada’s safe concentrations. Some of the highest concentrations were near Honey Harbour, a common launching point for campers and backpackers to reach Beausoleil Island, part of Parks Canada’s Georgian Bay Islands National Park.

The following year, her organization released its own study suggesting that, given high flow rates in the St. Clair River, water levels in Georgian Bay could drop roughly three-and-one-half feet below 2013’s record low by 2030.

“That’s only six years away,” Muter said. “That’s not very far to be able to plan to prevent that from happening.”

Change of Franklin Island Wetlands. (Photo courtesy of Dr. Patricia Chow-Fraser)

Such a drop by 2030 could result in “huge economic and ecological harm to Georgian Bay,” she added. Marinas will be left high and dry, cottage values will plummet, Muter believes, and local governments that rely on cottagers and tourists to strengthen their tax base will take a huge economic hit.

“It will be a disaster. And if this was happening in the United States,” said Muter. “I can tell you Americans would be dealing with it. Georgian Bay would have been declared an ecological reserve.”

It’s still early to tell what impact the dead tree zones have had on fish and wildlife communities within affected coastal wetlands in Georgian Bay. Montocchio is crunching the data on fish community impacts, but published results are likely years away. Chow-Fraser has begun looking at how shoreline and meadow species have recalibrated with the return of higher water levels.

“The literature will have us believe that within three or four years of inundation, the vegetation is going to come back,” Chow-Fraser went on to tell lecture attendees: “They haven’t returned yet.”

Yet, with projected water level rises and increases in variability, the curious sight of dead and dying trees circling coastal wetlands throughout Georgian Bay will, by all accounts, become a far more common sight.

The Georgian Bay we see today is “the sum total of all the history of water levels that preceded it,” Chow-Fraser later told Great Lakes Now. “Is there anything we can do to change the pattern of water level fluctuations? I don’t think we can because I don’t think we know enough.”

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Even in Canada, where water prices are low, aging infrastructure and rising costs are a problem

Adaptation vs. Mitigation: Canada’s national climate change adaptation strategy needs balance

Featured image: Photo courtesy of Dr. Patricia Chow-Fraser