I Speak for the Fish is a monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor Kathy Johnson, coming out the third Monday of each month. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit Public Television. Check out her previous columns.

I Speak for the Fish is a monthly column written by Great Lakes Now Contributor Kathy Johnson, coming out the third Monday of each month. Publishing the author’s views and assertions does not represent endorsement by Great Lakes Now or Detroit Public Television. Check out her previous columns.

I had to see the muskie site for myself. My husband and I discussed our plan as we wound our way down the narrow gravel two-track. The lane was the dividing line between acres of rectangular ponds roughly the size of peewee football fields.

We slowly rolled past acre-after-acre of fish-rearing ponds. A lack of trees or any kind of shrubbery gave it a starkly human-made feel. An occasional sign denoted the species being raised otherwise there was nothing to distinguish one pond from the next.

We checked two locked gates before finding the one that had been left open for us. Three ponds were evenly spaced in a straight row. The perimeter of the entire area was secured with a chain-link fence.

The surface of the water was a good ten feet below the ground level. The ponds looked like giant swimming pools with only a couple of feet of water at the bottom. Black rubber liners spanned the bottom of each pond and extended halfway up the steep banks.

My husband and I spoke in hushed tones because the behavior we wanted to capture on film would only last a split second. We needed to be ready and very lucky.

Raising muskie

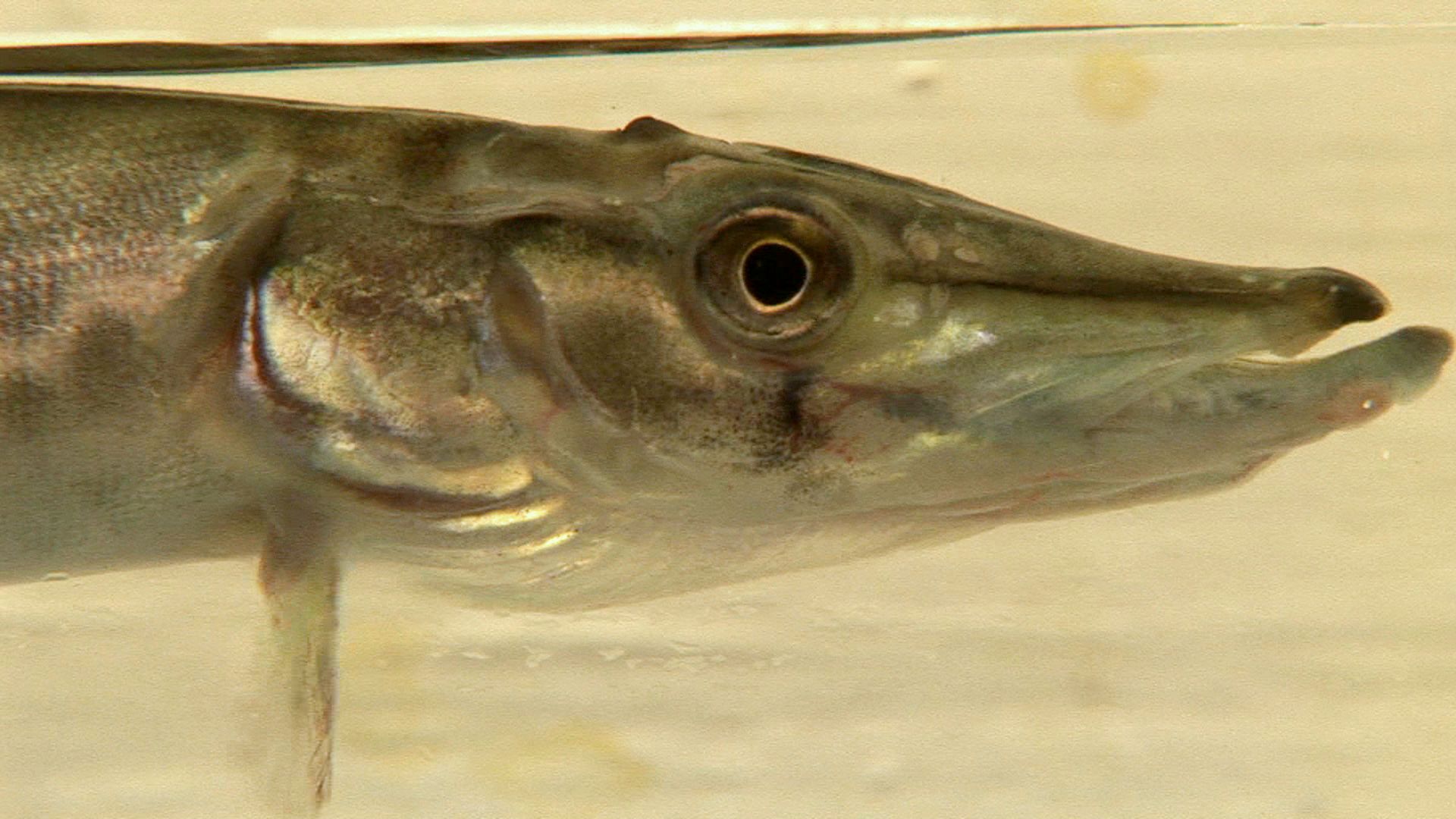

Great Lakes spotted muskie fingerling raised at the Wolff Lake State Fish Hatchery in Mattawan, Michigan. (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

The Michigan Department of Natural Resources has been raising and stocking muskie since the 1950s. I’ve previously written about this illustrious fish, Meeting the Mysterious Muskie and Who caught the world’s biggest muskie, and this month Great Lakes Now will feature a segment on the Michigan DNR muskie rearing program.

Here are some interesting facts that didn’t make the final cut:

Disease prevention is one of the important but not visually interesting parts of the process. Collecting adults from the wild presents the risk of bringing outside contaminants into the hatchery which could be catastrophic.

The researchers take preventative measures at nearly every step to prevent disease transmission.

During the adult egg collections, the fish are removed from the Detroit River and placed in a large iodine bath to rinse off every drop of river water. Once the eggs are fertilized, they are also placed in small bowls and given an iodine bath dockside.

As each group or family of eggs is checked into the hatchery, they are once again bathed with iodine.

The iodine disinfects without any adverse effects on the fish or eggs.

When the eggs and milt are collected, a tissue sample is also taken from each adult and sent to Lansing for testing. Each group of eggs is isolated until their parents’ test results come back. If any parent tests positive for any disease, their offspring will be removed.

Even the hatchery’s welcome mat functions as a disinfectant.

On the inside of the hatchery doorway is a large squishy wet mat. Our feet sink two inches down allowing some sort of sterilizing fluid to saturate the bottoms and sides of our shoes. Effectively cleaning everyone’s shoes to prevent us from tracking in contamination.

These are just a few examples of the numerous disease prevention measures the hatchery staff takes throughout the process.

How many are there?

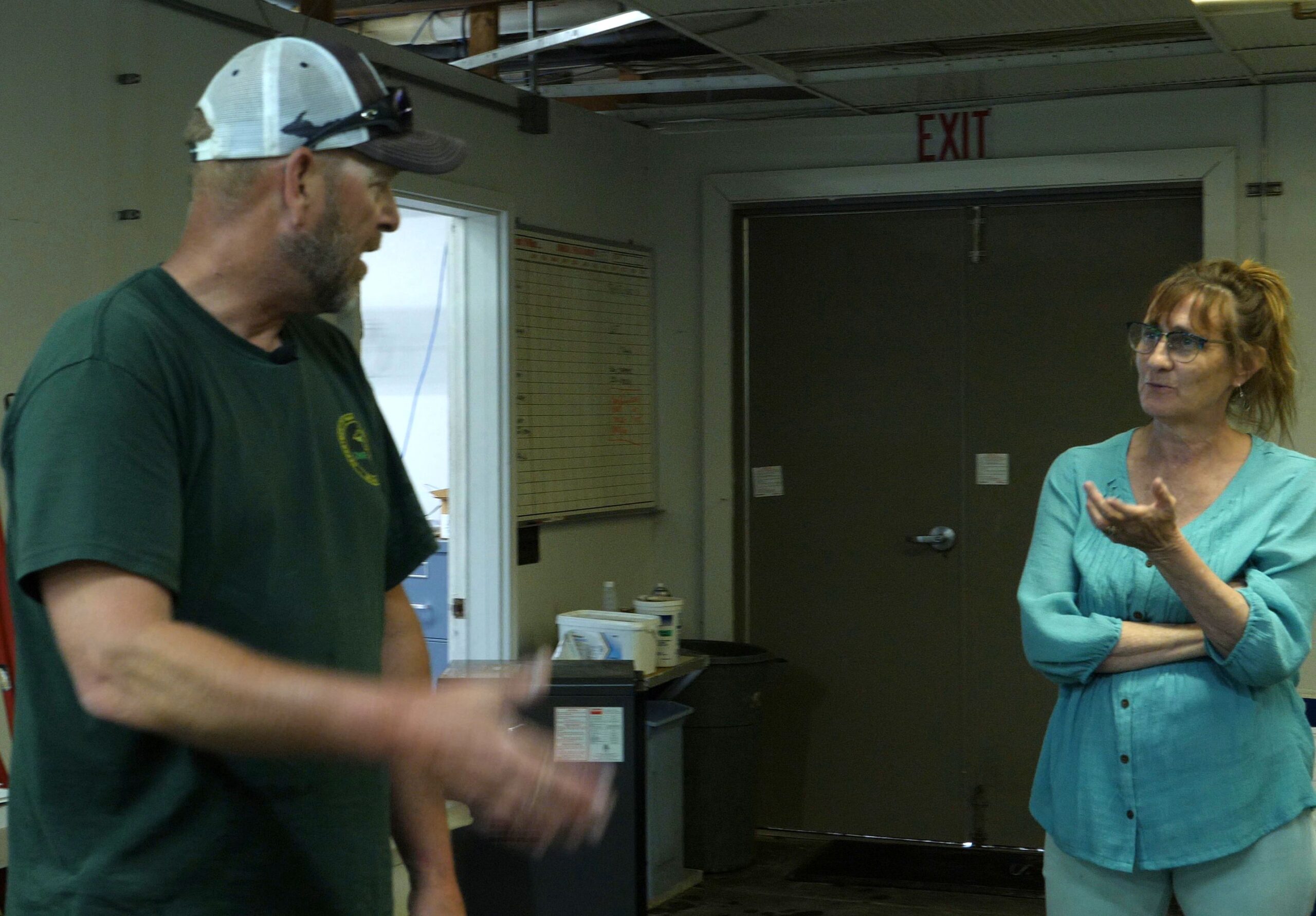

I Speak for the Fish columnist Kathy Johnson talks muskie with Matt Hughes manager of the Wolff Lake State Fish Hatchery. (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

One of the most critical pieces of information for the hatchery to know is how many eggs they have.

So, how do they know?

A female muskie can produce 40,000 or more eggs. And the team might capture three or four females in one night. It’s not practical to hand count 120,000 – 160,000 eggs. But the scientists have a way to get a fairly accurate count.

When the fertilized eggs arrive at the hatchery, the staff uses test tubes, petri dishes, and triple hand counts of a specific volume of eggs to extrapolate the overall total for each family group.

Having an accurate count at every step in the process is important.

The Michigan DNR’s goal is to stock 40,000 muskie fingerlings each year. With a large percentage lost at every step in the process, the hatchery has to start with hundreds of thousands of eggs to successfully stock tens of thousands of fish. Such is the nature of hatchery-rearing fish, but muskies have the added challenge of being highly cannibalistic.

The key to keeping muskies from eating each other is making sure they have plenty of other options without being wasteful because it turns out minnows are really expensive.

So, how do you know if there are enough minnows in the pond, but not too many? Do you need to place an order for a delivery? Or, can you wait a couple of days?

Knowing how many fingerlings are moved from the inside tanks to the outdoor ponds is the starting point. Knowing how many minnows have been added and how much each muskie can eat are also key, as are years of experience raising muskies in these ponds.

Matt Hughes has been raising muskie at the Wolff Lake State Fish Hatchery for more than 20 years. He regularly drives out to the muskie ponds to gauge the minnow count. He is so skilled at measuring them that he doesn’t even have to get out of his truck.

Being the bait

Outdoor ponds where the Michigan Department of Natural Resources raises tens of thousands of muskie each year. (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)

When it comes to fight or flight, fathead minnows, which are stocked into the muskie ponds as food, have zero fight response. They’re 100% flight.

Understandably, their flight response is particularly high in the ponds given their status as the bait. The minnows are like a group of friends walking through a haunted house. At the slightest noise, they all scream and jump in unison.

In the fathead’s case, Hughes assured us that the sound of a car door slamming was enough for all of them to jump out of the water.

I thought — this I gotta see.

With my eyes fixed on the pond’s surface, I eased my car door open and slammed it shut.

The surface immediately erupted with thousands of tiny fish. It was just a flash of movement, and then they dissolved back into the water like raindrops on a puddle, leaving the surface rippling with tiny ringlets.

Hughes said honking the horn was an alternative method but we found it garnered little response. Although, as he also noted, the minnows wised up after the first slam or honk. Apparently, it’s universally true that saying “Boo” is less effective the second time around.

To see the whole muskie rearing process, check out this month’s episode of Great Lakes Now.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

I Speak for the Fish: The great seasonal flip

I Speak for the Fish: Carp are crazy about corn

Featured image: Great Lakes spotted muskie fingerling raised at the Wolff Lake State Fish Hatchery in Mattawan, Michigan. (Photo Credit: Greg Lashbrook/PolkaDot Perch)