In Douglas, Michigan, houses dot the coast of Lake Michigan, with wooden stairs — some newly built, others with broken steps — descending the steep hillside to give shoreline residents access to the narrow sandy beach. When winds grow fierce, waves crash against the boulders and large sandbags stacked along the base of these homes.

Marchiene Rienstra, 81, said when she bought her lakeshore home in Douglas, she knew she was risking losing it due to high lake levels and shoreline erosion. In the 36 years since then, the Great Lakes have reached record high levels, threatening businesses, homeowners and public parks.

“When the water was at its highest level a couple years ago, there was no beach to walk on,” Rienstra said. “You could see people’s stairs all in shambles, with shattered steps lying on the beach.”

The Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy (EGLE) has designated 250 miles of shoreline along Lakes Michigan, Superior and Huron as high risk for erosion. Rienstra’s property along Lake Michigan is included. To combat this erosion, EGLE issued over 3300 permits in 2019 and 2020 — five times what they would typically expect — to cities and property owners for projects such as steel walls or boulders stacked along the coast. EGLE also issued 143 temporary permits to cities like Douglas for the emergency use of sandbags to immediately threatened areas.

In December 2020, Douglas installed around 200 large sandbags on the city’s public beach, with an estimated cost of $93,500. When water levels decreased eight months later, EGLE told the city to remove the sandbags due to concerns that wave and sun exposure would cause them to deteriorate into microplastics.

These ‘hard’ responses to changing lake levels can damage fragile shoreline ecosystems, disrupting sand and water movement. The concern with this softer alternative is that the plastic from sandbags can deteriorate over time and pollute the Great Lakes, which provide drinking water for over 30 million people, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). So shoreline owners were asked in July to remove sandbags, a costly acknowledgement for cities and property owners that rapidly changing water levels have no easy solution.

As water levels become more erratic due to climate change, coastal communities around the world are experiencing similar problems. For example, Baylys Beach in New Zealand has experienced plastic pollution from sandbags that started deteriorating after a few years. In Malibu, California, plastic sandbags are banned due to environmental impacts, and East Hampton, New York, has considered doing the same.

Microplastics have existed in the oceans since the 1970s, but the term wasn’t coined until 2004 by marine biologist Richard Thompson at the University of Plymouth. Microplastics are now known to be everywhere, even in “pristine areas” like the Arctic, according to Allen Burton, a University of Michigan professor of ecosystem science and water management.

Burton said that microplastics from storm drains get into waterways and drinking sources when it rains. However, there is almost no published research on microplastics from sandbags. Burton thinks this is because people are more concerned about other sources of plastic since the sandbags would be a minor source in the grand scheme of things.

Hugh McDiarmid, EGLE spokesperson, said some people think burlap and sand are natural materials, but the burlap bags are held together by plasticized mesh.

“I think people will recognize right away that plastics aren’t something we want in our lakes,” he said.

McDiarmid also said removing the sandbags is not as labor-intensive as it sounds. “They can slit the sandbags, dump the sand on the beach or wherever it is, and walk away with the burlap and the plastic and we’re fine with that.”

Close up of Douglas Beach Park’s sandbags, October 2023. Photo by Astrid Code.

McDiarmid added that if property owners are still concerned about erosion, they can reach out to EGLE.

“There are a variety of options available to the property owners on water that we can help them explore,” he said. “If we have people kind of doing whatever they want … we can end up with some pretty massive structures that are damaging to other folks’ property along the shoreline.”

Options include ‘hard’ projects like sea walls, but these can redirect waves that damage neighboring properties to the south, said Suzanne Dixon, Douglas resident and local environmentalist. Lake Michigan’s sand beaches are caused by wind and waves depositing sand on the shoreline in a similar process to ocean beaches. Dixon said sea walls can interrupt the natural movement of sand from north to south.

“Hardening causes us to lose the sandy beach we have enjoyed along the east side of Lake Michigan,” Dixon said. “Sand must be able to move to nourish our beaches.”

On the other hand, simply removing sandbags and leaving nothing on the shoreline may not be enough to protect sand dunes from erosion.

Concerned about ongoing stability of the dunes, the City of Douglas has not yet removed the sandbags on their public beach. Lisa Nocerini, Douglas City Manager, said in an email that the cost is the main issue.

“It isn’t really about removing the sandbags, it is what is required once the sandbags are removed in order to keep the hillside stable that is going to cost a lot of money,” Nocerini said. “We do not believe it is a good idea in any way to remove those sand bags, and believe they should stay, and we can identify a way to cover them so that the plastic does not end up in the lake at some point.”

Dixon, who has lived in Douglas since 2001, said she attended city meetings and was concerned about initial debates about placing boulders on the beach to prevent erosion.

“The conversation fortunately turned from boulder dumping to geotextile tubes, installed by a professional environmental consultant,” Dixon said.

Although she sent the city council literature about sandbags, also known as geotextile tubes, Dixon said her personal opinion is that: “this was a public beach and that eventually the water would go down and that we needed to sit tight.”

Waves lap at the edge of the Lake Shore Resort’s beach access stairs, October 2023. Photo by Astrid Code.

For local business owners, though, high water levels affect their livelihood. Joe Milauckas, owner of the Lake Shore Resort in Saugatuck, said fluctuating lake levels affect his tourism-based business. He is also the founder of the Great Lakes Coalition of coastal property owners. They advocate for safeguarding the shoreline because, according to Milauckas, if there is no protection, they will potentially lose bluff vegetation and structures.

“The beach, of course, is our biggest amenity,” he said. “So whenever our beaches are gone, and it’s not accessible, that does impact our occupancy and our rates.”

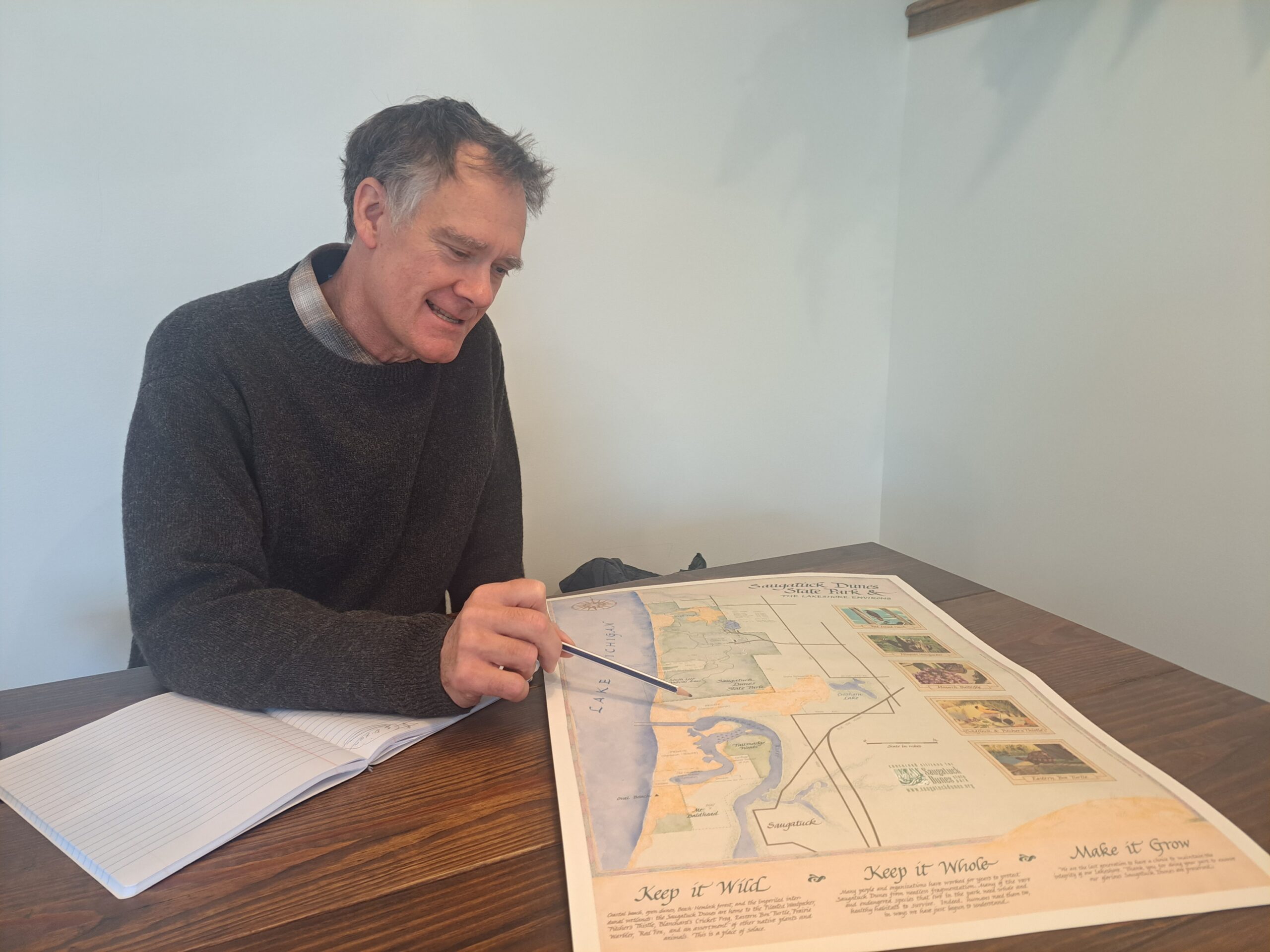

The debate on how states should protect the shoreline is complex. David Swan, founding board president of the Saugatuck Dune Coastal Alliance, said Michigan is at a “pivotal point” in terms of responding to fluctuating lake levels, especially considering the unknown effects of climate change on the Great Lakes system. Swan cited a 2023 report in the Michigan Journal of Environmental & Administrative Law.

“As with most wicked policy dilemmas, the best response may not be at either extreme—always armor or always withdraw—but somewhere in between,” the report, titled “Armor or Withdraw?” states.

The report recommends that state and local governments prohibit any new hard armor structures along the Great Lakes. Instead, they should allow the placement of temporary “flexible armoring,” such as sandbags, as long as they can be easily and swiftly removed. However, Swan explained that both types of armoring have drawbacks.

“Should we ever put anything on the beach that breaks down and allows plastic particulate matter into the Great Lakes which threatens tourism and fisheries? I would say no, that’s a really bad idea,” Swan said.

Saugatuck Dunes Coastal Alliance leader David Swan points to a map of the Saugatuck-Douglas shoreline, October 2023. Photo by Astrid Code.

Frederick Royce, 72, has lived on the lakeshore about 1000 feet from the Douglas public beach for his whole life. Royce installed sandbags on his family property in 1995, which were buried by sand and eventually uncovered in 2020. He’s surprised EGLE thinks the sandbags on Douglas’ public beach will deteriorate.

“I mean, they’ve been there three years,” he said. “My bags lasted decades and they were still good.”

Royce said he only had to remove his sandbags when excavators came to put in a seawall on a neighboring property, and the construction vehicles carrying boulders up and down the beach damaged them.

“I still dream about the water coming up and being right in my window,” Royce said. “That’s what you have as a homeowner who lives on the lake is, who’s going to win? Well, the lake always wins. So everything you do is just an interim solution to try to prevent the inevitable because you can’t stop the lake.”

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

Strong winds uncover spectacular features and long-lost structures

Shrinking Shorelines: Climate change-related erosion threatens Great Lakes coasts

Featured image: Sandbags sit on Douglas Beach Park, October 2023. Photo by Astrid Code.

5 Comments

-

Durning the high waters of 2019 , sand bags were uncovered that I put into the sand banks in 1972 & 1984 … Fully intact. These sand bags where the bags the farmers use for grain! They are still available !

True, some guidelines need to be established so cheap plastic one that are dissolving on ones property should be removed…. but not the grain and soil bags used throughout the industry! In my opinion !

-

Very fair to all parties and viewpoints and interpretations of historical data–

A very complex challenge to all stakeholders, and the general. public. -

The danger of losing homes to the lakes not only comes from the lakeside but, also from drainage miles in. Protect your property by not cutting down native trees and not planting grass. Plant native trees, flowers and grasses which don’t need as much water. Water plants only when necessary, don’t use automatic sprinkler systems. Do not pave driveways and walkways or if you must, install permeable pavement.

In the long run, it’s cheaper to move the whole house back from the lake bluff rather than build revetments or use sand bags. -

Bio-technical erosion control combines plants and rocks for a more natural and beneficial approach to long term erosion control.

-

All they need to do is increase flow through Niagara River area from Lake Erie is by 500 meters a second. Would take a bit of work but Welland Canal is capable of accomplish it. By comparison the Moses dam is capable of changing flow 7000 m3/s . They can drop lake Ontario by 3 or 4 inches per week when they so choose except during spring.