Editor’s Note: “Nibi Chronicles,” a monthly Great Lakes Now feature, is written by Staci Lola Drouillard. A direct descendant of the Grand Portage Band of Ojibwe, she lives and works in Grand Marais on Minnesota’s North Shore of Lake Superior. Her two books “Walking the Old Road: A People’s History of Chippewa City and the Grand Marais Anishinaabe” and “Seven Aunts” were published 2019 and 2022, and she is at work on a children’s story. “Nibi” is a word for water in Ojibwe, and these features explore the intersection of indigenous history and culture in the modern-day Great Lakes region.

A friend recently texted me a video she recorded while driving down a gravel road late at night. Out of the darkness, a snowshoe hare is illuminated by her headlights—a white streak, zig-zagging its way back and forth on the road, unsure which direction to run. Already changed into its white winter coat, wabooze was completely exposed due to lack of snow. It is mid-December, but the woods here are brown and the forecast is unseasonably warm.

I was touched by this little rabbit’s vulnerability. Using its instincts and inner clock, it had followed its evolutionary duty to camouflage according to the season. But even though the rabbit’s coat had changed, the rest of the world hasn’t.

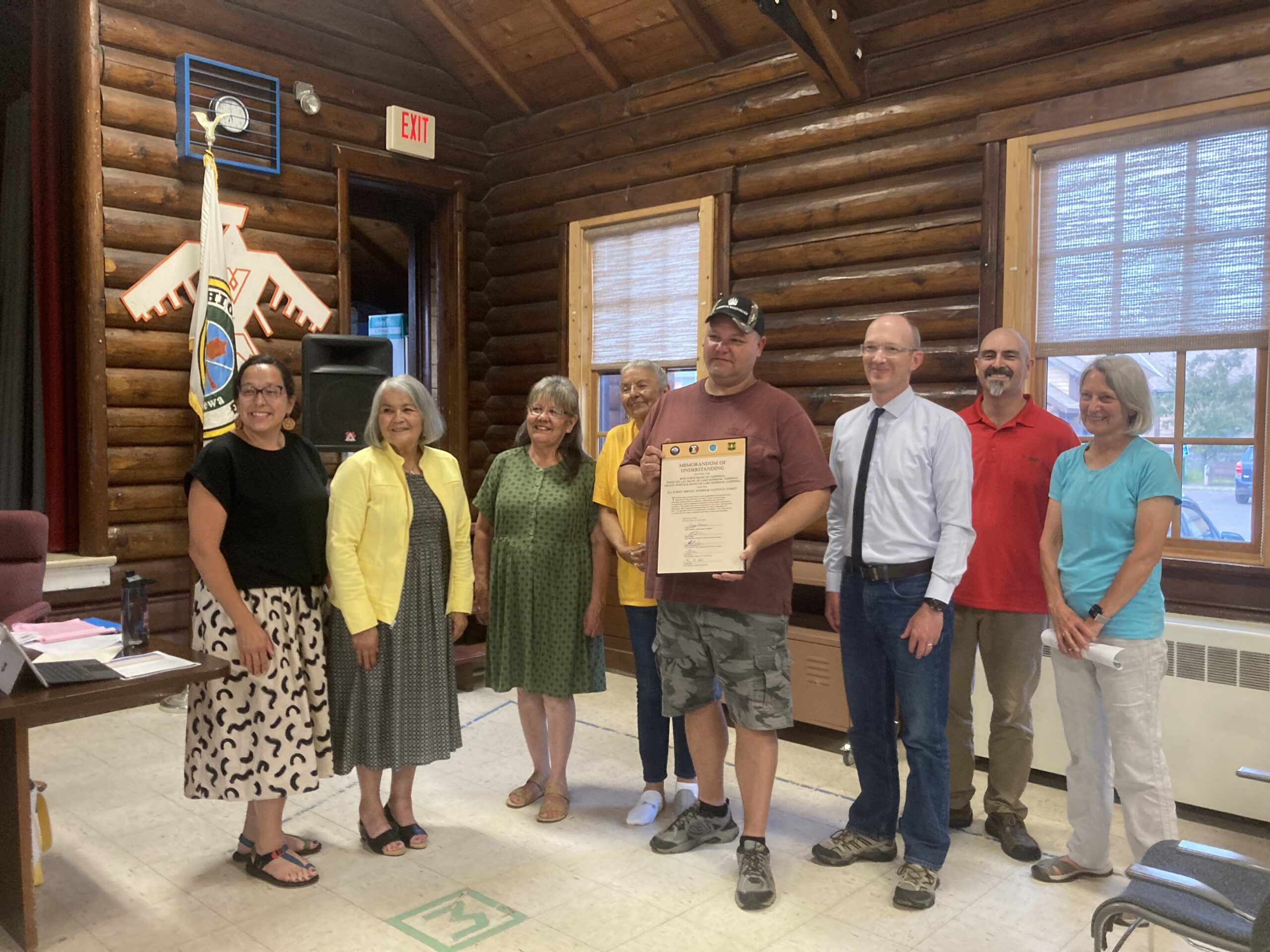

In Ojibwe country, change is understood to be a constant condition or state of being. Sometimes change is difficult, and sometimes change is good. A very good effort to change the way decisions are made across the Superior National Forest happened on May 2, 2023 when the Grand Portage, Bois Forte and Fond du Lac Bands of Ojibwe signed a historic Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the U.S. Forest Service.

Written collectively, with specific goals agreed upon and negotiated by all parties, the MOU provides assurance that Ojibwe people and tribal governments will be consulted on decisions big and small within the 3.3 million acre Superior National Forest. In the Band’s press release the signers from Grand Portage, where my family is from, stated:

“ . . . we are the people, Anishinaabeg, who live along the Gichigami, Lake Superior. We have an inextricably deep connection to our aki, land, and nibi, water. Waterways and trails have connected our communities throughout the ceded territories. We have lived here since time immemorial, long before our reservation was established by the 1854 Treaty of LaPointe.”

The Treaty of LaPointe was signed on September 30, 1854, and ceded 6.2 million acres of Lake Superior Ojibwe homelands to the United States. Under the treaty, the Bands retained their inherent rights to hunt, fish, and gather. The ceded territory includes all of what is now called the Superior National Forest, a territory managed by the US Forest Service which includes the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness

Treaties, Memorandums of Understanding and other formal accords carry a lot of weight. At least they should. Treaties matter and our agreements with each other are promises we can’t afford to break. As the MOU states:

“The Tribes were the original stewards of lands now encompassing the Superior National Forest and view the continued availability and use of resources within Superior National Forest as essential to perpetuating their identity and way of life. Those resources include the land, water, wildlife, lake and stream fisheries, forests, fruits, wild rice, medicinal plants, sugarbush, and other locations and habitats of traditional cultural significance that the Tribes and their members have conserved, protected, and relied on for centuries.”

This brings me back to wabooze—the rabbit. And makwa, mooze, name, namegos, manoomin, aninaatigoog and nibi. Because without including the rabbits, bears, moose, sturgeon, lake trout, wild rice, maple trees and water in our formal agreements, human beings can say or agree to anything we want. But if we don’t give proper voice and consideration to all living things, we are in essence denying these living beings their inherent sovereignty. And who are we, as human beings, to deny the original sovereign holders and protectors of Earth their right to exist and flourish?

View of Grand Marais and Lake Superior, December 2023. (Photo Credit: Staci Lola Drouillard)

The power of self government

An MOU between human beings and trout might look like this:

“The Parties acknowledge and recognize that namegos are sovereign beings with shared responsibilities to past, present and future generations of namegosag. Sovereignty includes the inherent right and power of fish beings to govern themselves and their affairs.”

You get the idea. Acknowledging the inherent sovereignty of plants and animals is not unprecedented. People like Frank Bibeau, an attorney and member of the White Earth Band of Ojibwe, have already worked to set a legal standard for the defense of natural resources, more specifically, manoomin (wild rice) and the waterways that support the health and protection of wild rice.

In December 2018, the White Earth business committee adopted the “Rights of Manoomin” ordinance, which recognizes wild rice as having the right to “exist, flourish, regenerate, and evolve,” as well as inherent rights to restoration, recovery, and “a natural environment free from human-caused global warming impacts and emissions.”

A central tenant of sovereignty is the existence of usufructuary rights—a legal term where a being is granted the right to use the property or asset belonging to someone else. And, while using the property, is granted access to the profits derived from the asset so long as it is not altered or destroyed in the process.

We only need to travel as far as the Straits of Mackinac, the heart of Ojibwe aki, to find one of the biggest threats to the inherent sovereignty and usufructuary rights of nibi—water.

Enbridge’s Line 5 is a Canadian oil pipeline that runs from Superior, Wisconsin to Sarnia, Ontario. There are two major lines that run underwater at the Straits of Mackinac, where Lake Michigan meets Lake Huron. These pipes carry approximately 540,000 barrels, or 22.7 million gallons of oil and natural gas liquids per day. The pipes have been in operation since 1953, and over time have been damaged by ship anchors and plagued with other structural issues.

Enbridge now has plans to construct what it calls “The Great Lakes Tunnel” underneath the straits. In spite of Enbridge’s claims that building a tunnel will resolve safety issues, many people concerned about the connection between oil, water quality and climate change say the pipeline should be closed entirely.

According to Chel Anderson, author of North Shore: A Natural History of Minnesota’s Superior Coast, water conditions in Lake Superior “have been tracked with greater scrupulousness than almost any other feature of the Great Lakes watershed. Using these continuous records of observation, we know with certainty that the ice free navigation period on Lake Superior has been extended by sixteen days in early winter and has reopened seventeen days earlier at winter’s end.

Snowless conditions at Pincushion Ski Area in Grand Marais. (Photo Credit: Staci Lola Drouillard)

As Chel cites in her careful research, a 2012 Journal of Climate study of ice cover on Lake Superior showed a 79% decline between 1973 and 2010. She also cites the work of Jay Austin and Steve Colman of the Large Lakes Observatory at University of Minnesota Duluth, who extrapolate the rate of ice decline into the future, estimating that, “at the current rate of decline of ice cover, Lake Superior will be ice-free in a typical winter” by 2040.

It’s December 2023 and there is no snow in Grand Marais, Minnesota. The brave, wabooze—a teacher in a white fur coat—is here to demonstrate that early winters without snow put all of us at risk. As human beings, it is in our nature to adapt and change, just like that little rabbit. As human protectors of Anishinaabe aki, we need to honor the inherent sovereignty of the systems of life that support us, and strike a memorandum of understanding with nibi—the source of all life. Changing our ways is going to be hard, but the alternative is going to be much harder.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

The Four Sisters: Bangs, Lugalette, Bannock and Frybread

Nibi Chronicles: Grand Portage Water Warriors

Featured image: MOU signing with tribal and USFS officials at Grand Portage Nation. (Photo courtesy of USDA Forest Service, Superior National Forest)