Four weeks into her new position as the top executive of the U.S. EPA’s Great Lakes office in Chicago, Teresa Seidel has mixed news for the region.

She readily accepts the goal she inherited from her predecessor to clean up decades-old contaminated sediment sites in the region by 2030, a mission she refers to as a “moon shot.” The sites, known as Areas of Concern (AOCs), are on a list developed in 1987 and their continued presence makes it hard for the region to shake its derisive “Rust Belt” stereotype.

But her enthusiasm for the 2030 goal comes with a dose of caution.

Achieving it will be a challenge unless more non-federal financial sponsors can be convinced to share expenses, said Seidel, a self-described realist.

The federal government picks up 65% of the cost but non-federal sponsors – the states, responsible parties or other interests – have to kick in 35%. And that can be a heavy lift as the parties responsible for the pollution may no longer exist and other entities are reluctant to shell out millions of dollars for a problem they didn’t cause.

Seidel came to the EPA Great Lakes office from Michigan’s Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy following a 30 year career that included 15 years focused on water quality.

Great Lakes Now recently spoke with Seidel and she elaborated on her priorities and shared a message about how citizens can contribute to the health of the Great Lakes.

Think creatively

On securing those elusive non-federal sponsors, Seidel said she will focus effort on working with staff and the states to come up with ways to identify in kind work. And to think more creatively about how potential partners can be convinced to make investments in Michigan and around the region.

With the right leadership and some creativity, it can be done for large scale projects and Milwaukee is proof.

Milwaukee and the EPA recently announced a record $450 million investment in cleaning up legacy pollutants in the Milwaukee estuary, a confluence of three rivers that empty into Lake Michigan. Strong local leadership and investments from the state, business and others contributed to securing the federal funding.

But in Michigan and Detroit, a similar cleanup of the 3.5 million yards of toxic sediment in the Detroit River lags. The state of Michigan did not put money in its 2024 budget specific to the Detroit River’s needs, in spite of pleadings from a large, diverse group of interested parties that included not-for-profits and municipalities.

Seidel declined to comment on Michigan’s lack of financial support for the Detroit River. But said the fact that Milwaukee and Wisconsin figured out the funding and Detroit and Michigan haven’t “stands out.” She said there are lessons to be learned about how Milwaukee and other AOCs came up with the non-federal partnership component.

Nutrient runoff

In addition to working on the Areas of Concern, Seidel will emphasize how we address nutrients across the Great Lakes basins. Specifically, in Lake Ontario and Lake Erie’s western basin.

Nutrients that runoff from farms are the key contributor to Lake Erie’s notorious algal blooms, like the one that plagued Toledo in 2014. It caused residents to wipe out bottled water supplies for three days when officials ordered a ban on drinking tap water.

There’s a great opportunity in the western Lake Erie basin for states to collaborate with federal agencies on the phosphorous issues that contribute to algal blooms, according to Seidel. She wants to help figure out how the region can act cumulatively instead of individually.

The western Lake Erie basin is approximately six million acres centered around Toledo and land use is primarily agriculture.

Work on Lake Erie’s algal bloom issues is complex and spans departments within the EPA. Separate from Seidel’s Great Lakes responsibilities, the EPA’s Office of Water in September approved Ohio’s plan to reduce phosphorus pollution to Lake Erie’s western basin.

“This action will help restore water quality in the western basin and support important uses like drinking water and recreation,” the agency said in a press release.

But the non-profit Alliance for the Great Lakes isn’t buying the EPA’s plan. It noted the “millions of dollars of investments over decades,” yet the lake remains plagued by harmful algal blooms. The alliance said the EPA was “doubling down on the same, tired approach” that hasn’t worked.

Personal responsibility

Asked about advice she has for citizens of the region who care about the Great Lakes and their health, Seidel said, “it’s a partnership.”

Seidel was raised on Lake Michigan and water quality has been a passion since she was a child. The government can help, she said, but it starts with the choices we make about water and it takes a commitment.

“We all have a role and responsibility” to keep our waterways safe, she said.

Catch more news at Great Lakes Now:

The Great Lakes Compact at 15: Region celebrates, veteran policy experts caution against complacency

Book Review: Wisconsin author touches third rail of drinking water issues in new book

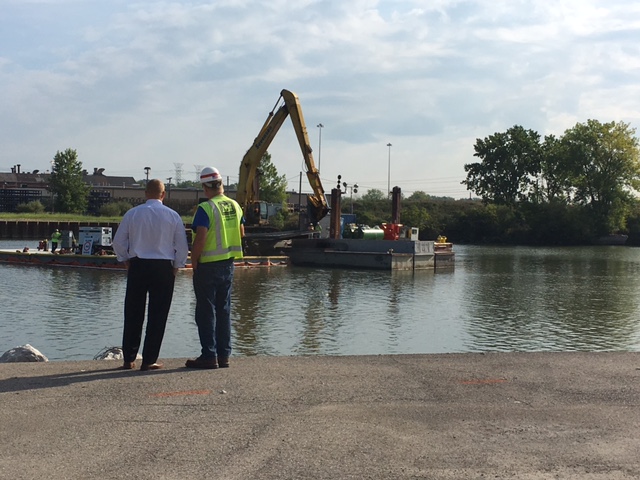

Featured image: Contaminated sediment remediation in the lower River Raisin, Photo by USEPA